“Rei Naito: Mirror Creation” – on a sunny day, on a rainy day

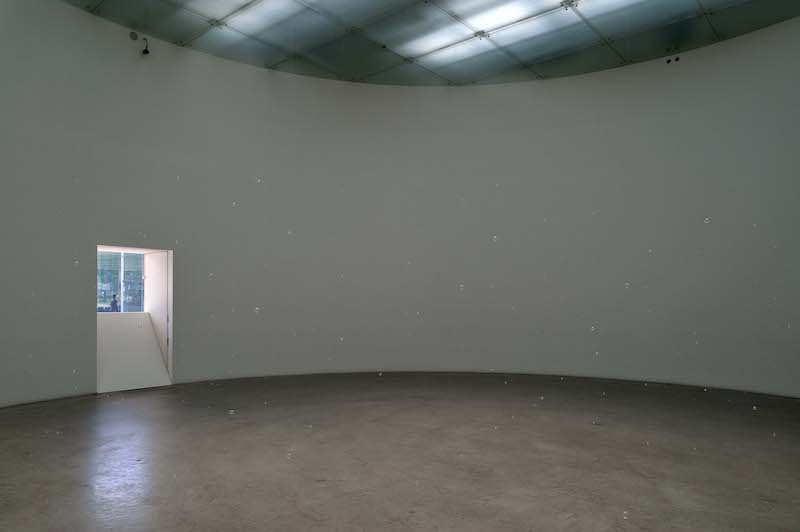

Rei Naito – The spirit (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” at 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa. All images (except where otherwise noted): photo Naoya Hatakeyama, courtesy 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

Rei Naito – The spirit (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” at 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa. All images (except where otherwise noted): photo Naoya Hatakeyama, courtesy 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

I had initially planned to travel from Tokyo to Kanazawa by shinkansen to see “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation” at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, on July 16. In an ordinary year in Tokyo, even if the rainy season lingers until around the middle of the month, one can start to see summery blue skies and gigantic columns of clouds in July, and the second half of the month is generally marked by deadly sweltering heat. Viewed positively, one could say it is a month full of climatic variety. However, this July was consistently rainy. Having just checked the records again, even now I am astounded that there was just a single day during the whole month when it did not rain. In other words, it rained on 30 out of the 31 days. Naturally, the hours of sunshine were dramatically fewer than normal, reaching a total of just 47.7 for the month. This is the lowest figure since the government began keeping records in 1891, and just 30 percent of the average for July. In the end, the rainy season was not officially declared over until the beginning of August, leaving us gazing at somber, damp skies day after day. In such circumstances, there is no way a person could not feel down.

It would have been bearable if it were just the overcast skies typical of rainy season. But at the start of July, the activity of the front caused storm trains to remain in the same position for several days, with torrential rain falling continuously. In the area around Hitoyoshi in southern Kumamoto Prefecture, where the Kumagawa River burst its banks, large-scale flooding resulted in heavy casualties and forced many people to evacuate their homes. This year, the area was also affected by the spread of the coronavirus. Because there is urgency associated with evacuation facilities, they inevitably end up being crowded. Behavior designed to save lives may in fact end up hastening the spread of the disease. And the volunteer staff from outside the area that are now an indispensable part of the recovery effort may actually bring in the virus. Consequently, even by the autumn, fresh scars left by the flooding were still visible.

The reason I have gone on so long about the weather and disasters is because I have doubts concerning the established wisdom that there is no direct relationship between such events and viewing exhibitions. The insides of art museums are neutral spaces detached from such transitory realities, where anyone can engage one-to-one with the artworks themselves. Certainly, the physical conditions allow this. However, looking at art is not a matter of physics alone. Our physical and mental state on the day cast a shadow over this activity in the form of the “weather condition” of our bodies viewing the works. This is different, then, from the kind of measurement error or noise that in normal circumstances can be ignored. Or rather, the act of viewing includes such feelings both inside and outside our bodies. And few artists have confronted this fact as sensitively or as earnestly as Rei Naito.

Rei Naito – Untitled (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

Rei Naito – Untitled (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

Speaking of mental states, the spread of the coronavirus has had a huge impact not only on people’s physical health but on their psychological wellbeing. Its influence ranges from the workplace to the details of our daily lives. Even if we are lucky enough to avoid getting infected, the fear of developing symptoms, the exercising of restraint in going outside, the limitations on interacting with new friends, the marked decline in recreation, and the uncertainty surrounding income and business cannot be communicated in an easy-to-understand way, such as the balancing of infectious disease control measures and economic activity. In fact, drinking at home has increased among the people I know, which in the worst case has resulted in someone losing their life due to the sudden aggravation of a disorder that can only be thought of as a consequence of this, while others have been urgently hospitalized. Cases of mild depression are too numerous to mention. Of course, because writers like myself have few options other than to work alone in cramped spaces, we are in a state of voluntary isolation to begin with. For a long time now we have communicated with editors solely via communication devices such as email and telephones, with so-called “remote work” having made advances for quite some time.

Nevertheless, because I often went to exhibitions at far-flung museums and visited the regions to do interviews and research, with the opportunities I do have to work outside eliminated completely due to the introduction of on-line lectures at universities, my mood has changed considerably. Even if this were not the case, even someone like myself, who is unsociable and used to staying at home alone, will become depressed if they are confined indoors for a long time, staring out the window at the constantly falling rain and not getting any sunlight. What might the mental state of someone who merrily travelled around the world be like? Similarly, it seems unlikely that the reason this series went without an update for the longest period since it began following the publication of its 92nd installment [in Japanese] on April 24, was solely due to the unavoidable circumstances in which art museums were closed and there was nowhere to go. If the spread of this coronavirus becomes protracted, the seriousness of the situation will undoubtedly become so clearly apparent that it will be no longer be able to be covered up via easy-to-understand media coverage.

Because of this situation, the honest truth was that I was quietly looking forward to my first visit to a faraway exhibition in some time, which was scheduled for July 16. But viruses are not in the habit of considering such trivial circumstances. In Tokyo, following the so-called “first wave” that reached a peak in April, the state of emergency was lifted and the Tokyo alert revealed itself to be in name only. The number of infected people remained low, and the virus suddenly started spreading again in July, resulting in an unexpected second wave, with the number of new cases per day quickly exceeding 200 on the 9th and setting a new record of 243 on the 10th. During a lull in which things seemed to have settled down slightly, I decided to head to Kanazawa, and while I had booked all my tickets, shinkansen seat reservations included, I still felt extremely apprehensive about heading from Tokyo to the country in such a situation, and after thinking about it I ultimately decided to postpone my trip. Thinking about it further, however, I realized that this Rei Naito exhibition itself had been postponed for two months due to the sudden spread of the coronavirus, and that it had only just opened at last on June 27. It was not only exhibitions. Everything in the world was being postponed. The biggest of these was the Tokyo Olympics. This historical, great undertaking in which the national prestige was at stake was to be “postponed.” Whatever the event, it would have been no surprise whatsoever if it had been put off. In the end, it was not until August that I was able to go to Kanazawa.

Rei Naito – human, matrix (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

Rei Naito – human, matrix (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

But this series of events made me think again. There are things called exhibitions that have firmly set dates, and as long as you go to the proper place at the proper time without mistaking the museum’s hours and days on which it is closed (though in fact this happens often), you can enter the museum and view the works inside until you are satisfied. However, that such an experience is guaranteed is itself nothing more than an artificial, institutional guarantee, hidden within which is the hollowness that if something untoward happens it may suddenly vanish as if it were a lie. In addition, the restricted admission format Rei Naito has often used to present her works is different both from the format commonly referred to by such easy-to-understand names as “restricted admission” that is now used reluctantly, and from the consideration shown by European art museums in restricting the number of visitors to the optimum number for viewing the works. By this I mean that the very experience of viewing something inevitably retains as its true nature something akin to the tea ceremony concept of ichigo ichie (treasuring every encounter as a once-in-a-lifetime experience), and even if it seems as if one can control this by means of the virtual system of the museum, as long as the world, which as a vessel is far larger, is the way it is, this is an impossibility, and what Rei Naito is attempting is a single gesture seeking to open the museum up to this largeness. And of course, “seeing something” is contiguous to the act of the person trying to see, to the place they are trying to get to, and to the date, time and season, and is almost inseparably connected to the climate and events surrounding that person and their physical and mental condition.

This may seem like an exaggeration, but when I thought about this, I realized that being able to see something is – to an extent far greater than we ever considered until now – a kind of unexpected stroke of luck, even a blessing. I also thought that the phrase “one place on the earth” that seems to perfectly describe Naito as an artist to date was presaging this. Certainly, being present at a particular exhibition (as a place) is invested with a kind of “one time only” individuality, and cannot under any circumstances be substituted with another person or date. If so, how exactly can we give such an experience deliberateness in terms of date and time? If it can be postponed due to unforeseen circumstances, then this, too, would surely be possible. Even not being able to get there at all is a perfectly reasonable possibility. If it has to be postponed out of necessity, the only thing we can do is accept this and wait for another opportunity to arrive.

Fortunately, on August 5, the day I was finally able to go to Kanazawa, most of Japan was covered by an anticyclone, and sure enough when I stepped off the shinkansen at Kanazawa Station I was immediately struck by the midsummer sun. There was not a single cloud in the sky, and though I had no idea of it at the time, it was the very start of a record-breaking heat wave that would last for a long time to come. I hurried to the museum, arriving when it was still early in the afternoon, and went straight to the galleries hosting the Rei Naito exhibition. It was as if the seemingly endless postponement and the mood swings I had experienced up until then had never existed. I took my time, looking carefully at the works in each gallery, and when I finished, went back and looked at everything again. Then I went back and stood or sat in front of the parts of the exhibition that particularly interested me, verifying through the act of “seeing” the weather and my own physical and mental condition on that day, accepting that was my own state on the day and turning that over and over in my mind. And in the process of doing this, I think I was able to understand the meaning of the words “mirror creation” that make up the title of this exhibition.

Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

Rei Naito – matrix, untitled, human (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

Rei Naito – matrix, untitled, human (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

When I think about it, no other artist is as unrelated to the rather extravagant word “creation” as Rei Naito. Or perhaps instead of “unrelated,” it would be better to say “has carefully maintained a distance from it.” As suggested by the Creation in the Bible, creation means to make something from nothing. However, the artist Rei Naito has done the exact opposite to this, in that she has shown more tangibly than anyone else the true form of the world, how to accept it as it is, and that such things are actually possible, all through the act of “seeing.” Such things are not usually described as creation. The concept for this exhibition was apparently put together beginning in 2018, but the elements that make up the exhibits are essentially not very different from the past. So, what is it that can be called newly created? The key to understanding this actually lies in the word “mirror” that modifies the word “creation.” This word calls to mind an image of two things “reflecting” each other. But it also suggests two things repeating. And repetition is also an act far from creation.

However, when we think like this, we are thinking of “creation” in terms too close to the Creation from nothing described in the Bible. Perhaps a case in which it is not unnatural to add the name creation to an act of “mirror”-like repetition is (biological) reproduction. Because there is nothing so deserving of the name creation as the birth of a new life. And yet reproduction is by no means creation from nothing. On the contrary, life never arises from nothing. The only thing that nothing can ever give rise to is nothing, which is precisely why the creation of heaven and earth is something beyond human understanding that only gods can achieve. But the creation of reproduction would not be possible without genes that exist in advance in an unbroken line. Moreover, with the exception of parthenogenesis, genes cannot increase on their own, and life cannot be renewed without the “mirroring” of different information by way of DNA. Which is why I felt that “mirror creation” undoubtedly had some kind of connection to reproduction.

But before that, I wrote that we cannot separate the act of “seeing” from the seasons, the weather and our physical and mental conditions. If we were to take this literally, then surely between seeing the exhibition “Mirror Creation” and the spread of the coronavirus there would arise a connection beyond coincidence. And because this could in no way be a positive association, even accepting that the degree would probably be different from person to person, if it floated to the surface of somebody’s mind, they would undoubtedly quickly sever or drop that association. However, at a level completely separate from whether this association is imprudent or not, a virus (retrovirus) certainly reflects like a mirror image (reverse transcription?) a person’s DNA, in which sense it carries out creation in the form of reproduction. But because a virus cannot reproduce without borrowing another’s genetic information, or in other words, cannot reproduce on its own, it is difficult to define it as a living thing, and so what viruses do is not normally referred to as reproduction, which if true means that viruses are not “creative.”

But what is a living thing to begin with? People may try their best to define it, but a living thing is not language, so there is no way it can be defined through the workings of language. At the best, such a definition can only ever be an approximation. If this is true, then who can declare that what a virus does is not reproduction but multiplication, and that because of this a virus is not a living thing and therefore devoid of any expression of creativity? Rather, perhaps the very thing that viruses do is “mirror creation” in the strict sense of the term. Of course, Rei Naito’s naming of this exhibition had nothing whatsoever to do with the novel coronavirus pandemic. The title was conceived long before the pandemic occurred. However, confronted with the reality of the timings of two things that were conceived or occurred completely unrelated to each other overlapping without one realizing it, so that they occupy the same space and time and “mirror” each other like reflected images (though extremely similar down to their details, they are fundamentally different in being laterally inverted, which is to say more essentially different things arise because they are similar), I cannot help feeling that the convenient word “coincidence” that people use so freely is itself losing its usefulness.

Rei Naito – matrix (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

Rei Naito – matrix (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

With these thoughts going through my head, I slowly and repeatedly walked through the exhibition venue while ruminating again and again on the experience of “viewing/seeing.” Even leaving aside the question of whether repeatedly walking itself is a creative act in the sense of “mirroring” my own steps, I think this was reflective behavior. In time, it seemed as if the experience of “viewing ” this exhibition was reflected inside my own mind. In fact, because this copying of my steps was repeatedly “mirrored,” even now when the exhibition has ended and I am writing this, it dwells in my mind like a mirror image and returns now and then unexpectedly. This tends to occur in particular on pleasant, fine autumn days like today. But because I am not a machine, naturally such “depicted” past experiences are not perfect recreations of the physical circumstances of the moment in question. I simply “reproduced” “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation” in the context of the weather and the physical and mental state I was in at the time.

In addition, as anyone who has actually experienced this exhibition will have realized, regardless of their size, in many cases the materials that make up the works in the different rooms, including glass and beads, water drops and mirrors, and the surfaces of transparent balloons, have a multiplicative quality that continually gives rise to mirror images that seem to go on forever, and as these experiences accumulate it remains unclear until the end which of them constitute the substance of the exhibition. With a normal exhibition, because the paintings and sculptures on the walls and floor, or even the installations or videos, have separateness, in physical terms one can say the people viewing it share the same thing as a condition. With Rei Naito’s presentation, however, such identifiable separateness does not exist for even a single work. And added to this is the context of the presentation of the works in natural light, which changes by the moment and is greatly affected by the weather. Within “Mirror Creation,” the world doubles and doubles again, and there is even mirroring beyond the space of the museum, and this is replicated inside my brain so that even now it produces echoes. But are these really echoes? I get the feeling the exhibition itself was an echo of something. And that this echo was also an echo of something else. Just as the earthly phenomenon of the preservation of the species is always a “mirror creation” of the vestiges of the preceding species. This is not to say that the world Rei Naito presents us is a metaphor for reproduction. Of course, we cannot call this reproduction in the normal sense of the word, but if this is so then neither can we call the “mirror creation” of a virus reproduction in the normal sense of the word.

Installation view of “Rei Kamoi: Still Time” (2020) at the Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art. Left: Still Time (1968), collection Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art; right: Stand Still Time (1968), collection The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. Photo courtesy Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art.

Installation view of “Rei Kamoi: Still Time” (2020) at the Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art. Left: Still Time (1968), collection Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art; right: Stand Still Time (1968), collection The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. Photo courtesy Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art.

I still had some time to kill before I was due to view the works again in the evening, when for a limited time they would be illuminated, so I climbed the small hill just behind the museum (though the design of the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, is such that it is accessible from multiple directions) and headed to the Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art. Earlier, while checking how to get to the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art on the shinkansen, by chance (or was it not by chance?) I happened to notice that “Still Time,” an exhibition marking 35 years since the death of Rei Kamoi (aka Rey Camoy), was being held at the nearby Prefectural Museum. The dates of this exhibition more or less coincided with those of the Rei Naito exhibition. It goes without saying that the styles of the two artists are poles apart. To the extent that Kamoi was awarded the Yasui Prize at the age of 41 and became an extremely popular figure in the art world, resulting in him becoming exhausted to the point where he ended his own life, and to the extent that his depression was deep, that he insatiably pursued and depicted the darkness of people’s lives, and in the process suffered the anguish of this darkness and depression overwhelming the innermost depths of his own heart, it is difficult to detect similarities with Rei Naito. Notwithstanding this, however, when I at last made it to Kanazawa and found that two artists by the name of “Rei” were holding large-scale exhibitions at the same time on the same date at venues less than ten minutes apart on foot, I again felt a sense of “mirror creation.” And in fact, Rei Kamoi produced two versions of the painting Still Time, which is also the title of the exhibition, with more or less the same composition. So these two paintings also undoubtedly “mirrored” each other.

Rei Naito – What Kind of Place was the Earth (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

Rei Naito – What Kind of Place was the Earth (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

Then, instead of climbing the hill, I yielded to gravity and descended the narrow slope back to the “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation” exhibition. And I returned in two senses of the word (to the museum and to one of the light courts within it), calculating what time I had to leave while checking out the unostentatious lighting throughout the museum before finally going back again to look at Grace, the tiny work installed in one of the light courts “embedded” within the Museum. There, two thin ribbons were hung in such a way that they intersect in the middle, though depending on the weather conditions of this atmosphere in which we live, their shape and the place where they intersection vary, they dance about, rise and fall, and squirm so intricately that one cannot measure it even on the second hand of a clock, “mirroring” each other just like living things and nurturing life. Life? Really? But the truth is we are now living in a world in which no one knows whether we can call this life, or whether it is wrong to call this life. As Simone Weil, who Naito reveres and holds in high esteem, might have put it, resisting gravity, the arrow of death that influences every physical body possessed of mass, tying it to the ground and seeking to stop its movement, the two ribbons float in the air as if by the grace of God, bathe in the light of the late afternoon, and fly as if reaching for the blue of the sky that has already reddened slightly. Beyond that there is nothing but outer space.

Rei Naito – the spirit (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

Rei Naito – the spirit (2020). Installation view at “Rei Naito: Mirror Creation,” 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

Where did life come from to begin with? Why do the two chains that make up the double helix of DNA that carries genetic information “mirror each other”? As I viewed the spirit while pondering these questions, before I knew it the two ribbons took on the appearance of Watson and Crick’s double-helix model of DNA. Just as Weil sought to achieve grace even at the cost of her own life, even if the two ribbons appeared as if they had eluded gravity, what lay beyond was outer space with its lifeless vacuum. Nevertheless, in defiance of emptiness and gravity, we stubbornly never give up mirroring. No doubt this refusal to give up mirroring is imprinted on every particle of every eye of the human-like figures that visitors encounter here and there in this exhibition, figures that Rei Naito began making after the disaster of March 2011.

“Rei Naito: Mirror Creation” was held from June 27 through August 23, 2020, at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

“Rei Kamoi: Still Time” was held from July 31 through August 30, 2020, at the Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art.

Noi Sawaragi oversaw planning for the exhibition “Bubbles / Debris: Art of the Heisei Period 1989–2019” running January 23 through April 11, 2021, at the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art.