Imagination for recovery – Disaster and restoration

Kenichi Tanaka – (left to right)>: Haisen C (1964), oil on canvas; Still life 1 (1975), oil on canvas; Umibe no bochi A (1978), oil on canvas. Installation view at “Art Doctor in Town.” Photo courtesy Kumamoto Earthquake Kenichi Tanaka Painting Rescue Association.

2019, both the final year of the Heisei era and the beginning of the Reiwa era, will go on record as a year in which Japan suffered heavy damage from typhoons and as a year in which it lost cultural resources on an unprecedented scale. While they followed different courses, typhoons 15, 19 and 21 all approached in fall when seawater temperatures were still high and amassed energy in midair before making landfall in Japan or passing close by one after another. Enormous damage caused mainly by record-breaking heavy rain was inflicted on Chiba Prefecture (the Boso Peninsula) during Typhoon 15 and elsewhere throughout eastern Japan, including major flooding and water damage due to rivers overflowing and breaching their embankments and difficulties in draining this water. The details of this damage, which includes landslides in mountainous regions, have yet to be fully grasped (it was only recently that it became known that there was enormous damage to the trail leading to the ridge of Mount Osutaka, the crash site of Japan Airlines Flight 123 in 1985 and a place sacred to the families of the victims, as well as to the public road leading to the trail).

In May this year [2019] I visited the town of Mabi in Okayama Prefecture, which in July the previous year sustained heavy damage in the 2018 floods, and saw for myself the scars that have yet to heal. In August, when memories of this damage were still fresh, localized torrential rain in northern Kyushu caused by the development of a front resulted in flooding below or above floor level to more than 4000 households in Saga Prefecture. Some 50,000 liters of oil leaked from a flooded ironworks owned by Saga Takkosho Co. in the town of Omachi and was confirmed to have reached as far as the mouth of the Rokko River and the Ariake Sea. There was also factory-related damage during the 2018 floods, with aluminum left at a high temperature at a plant owned by the Asahi Aluminum Industrial Company in the city of Soja in Okayama due to flooding triggering a phreatic explosion. When I approached the scene of the accident in Soja, which borders Mabi, I saw that the plant had been left as it was at the time of the explosion, and this combined with the condition of the surrounding area gave me a good indication of the size of the area affected by the explosion and the furiousness of its destructive power.

But of the effects of the October 2019 typhoons, it is the flood damage to university libraries, public art museums and other academic research facilities caused by Typhoon 19 that is still fresh in my mind. According to the Tokyo Shimbun, there was serious damage to 86 public libraries and 14 university libraries in as least 13 prefectures, including Tokyo, Chiba, Saitama and Kanagawa. (1) At the Tokyo City University library in Setagaya, the underground part of the building including stack rooms housing 90,000 volumes out of the library’s collection of 290,000 volumes was flooded. As for art museums, all nine storage rooms at the Kawasaki City Museum were also flooded. This museum has preserved some 260,000 items, mainly works on paper, including prewar manga-related materials, which are not yet valued highly enough as cultural assets but expected to acquire greater importance in the future. The true state of the damage has yet to be reported, the museum not only experiencing flooding, but also unable to use its electrical system due to water entering the machinery and other rooms, and the lack of lighting and air conditioning making conditions even worse in terms of rescuing works from the flooded storage rooms. The museum has requested assistance from the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and while the agency has announced that, as was the case at the time of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, it will respond through the National Institutes for Cultural Heritage that operates Japan’s national museums, it seems that at present no actual measures have been adopted.

Regarding the impact on art museums of large-scale flooding and the long-term loss of power, in my 2017 book Shinbijutsuron (Earthquake art theory) I discuss in detail the cases that occurred at the Museum of Art, Kochi, in 1998 and the Rias Ark Museum during the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011, and I have also pointed out the imminent risk of similar events occurring at some of Japan’s leading contemporary art institutions, including the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, which sits on land between the Sumida and Arakawa rivers in Tokyo’s Koto Ward, and the National Museum of Art, Osaka, which is located entirely underground on Nakanoshima in Osaka’s Kita Ward. While there was no flooding of the Arakawa river in Tokyo during any of the recent typhoons, the fact that climate change is intensifying is only becoming clearer every year, and there will surely be pressure to put in place actual measures to deal with this risk. As well, in recent years there have been more and more cases of storage facilities being placed underground to avoid the impact of earthquakes, and though such facilities may be resistant to shaking, I wonder how resistant they are to flooding. Looking at what happened at the Kawasaki City Museum as reported in the media, it seems that the doors to the storehouse that ought to have been solidly built folded as if made out of paper, though apparently the cause is yet to be determined. So what exactly happened beneath the museum, which was suddenly inundated with rainwater and flooded in almost no time? In future, it seems that similar facilities will have to anticipate a range of circumstances and consider stricter standards with respect to not only fires (though this did prevent Shuri Castle in Okinawa burning to the ground) and earthquakes, but also flooding.

The Japanese archipelago is limited in size, and increases in the frequency of localized torrential downpours and the size of typhoons due to climate change are matters that can no longer be avoided. While it is something no one wants to imagine, we must assume that cultural assets will continue to fall victim to natural disasters. This fall, an exhibition highly significant in terms of considering this was held in Mifune, a town in the Kamimashiki district of Kumamoto Prefecture. However, because this exhibition was an independent project organized by volunteers and staged not at an art museum but at a rented public gallery at the nearest museum, it received next to no attention from the rest of the country. Held for just nine days (excluding days when the museum was closed) from October 26 to November 4 (though also available for private viewing from October 12 to 14) at the Koryu Gallery of Mifune Dinosaur Museum, “Art Doctor in Town” raised some extremely important issues on the subject of how we can pass on to later generations paintings and other cultural assets from the modern and later periods in disaster-prone Japan. After all, we appear to have reached the stage where it is no exaggeration to say that the entire country is the scene of one disaster after another.

Mifune suffered severe damage during the unprecedented series of earthquakes measuring seven on the Japanese seven-stage seismic scale that struck the Kumamoto region in April 2016. At the time, the former studio-cum-home of local painter Kenichi Tanaka (1926-1994) was destroyed. All of the paintings that were stored at the property, including several monumental works, were trapped inside the collapsed building. Local supporters who could not bear to see these works exposed to the rain in the rainy season and left to decay due to the spread of mold resolved to do something. With the aid of young people who came from outside the prefecture to help with the recovery effort, they opened a hole in the roof of the collapsed studio and saved around 150 works. After learning of this, world-renowned art conservator Kikuko Iwai, who was born in Kumamoto, agreed to restore these works for free, and this exhibition presented works by Tanaka that had been restored over several years together with an open restoration of the monumental work Umi no mukuro B (1967), which was particularly badly damaged and requires further, painstaking conservation work.

Kenichi Tanaka – Umi no mukuro B (1967), oil on canvas. Photo (taken before the earthquake) courtesy Kumamoto Earthquake Kenichi Tanaka Painting Rescue Association.

Left: Rescuing works from the collapsed Kenichi Tanaka residence (2016). Photo courtesy Kumamoto Earthquake Kenichi Tanaka Painting Rescue Association.

Right: Kenichi Tanaka – Umi no mukuro B (1967), (before restoration). Photo courtesy Iwai Art Conservation Laboratory.

Established to assist this extremely long restoration effort, the Kumamoto Earthquake Kenichi Tanaka Painting Rescue Association used crowdfunding via the internet to obtain funds for the Kenichi Tanaka Artwork Restoration Project. Because the actual work requires a large studio, once temporary measures had been taken the paintings were sent to the University of Tsukuba. Astonishingly, this was all done by volunteers. From a commonsense point of view, as with the aforementioned Kawasaki City Museum, one would expect the Agency for Cultural Affairs to be approached for official support. In the case of the Kumamoto Earthquake, however, the scale of the damage to cultural assets, including Kumamoto Castle, was extremely widespread. Inevitably, assistance for modern oil paintings fell behind. Furthermore, in cases like that of Kenichi Tanaka where works have been retained privately in local hands due to the artist’s affection for their birthplace, use cannot be made of schemes such as the Japanese Cultural Heritage Disaster Risk Mitigation Network, which facilitates mutual support among museums in Japan during natural disasters. There is no way of expressing this other than that they were truly cornered, but looking at it from a different angle, one could also say that Tanaka’s paintings were able to be protected because of his very private and affectionate nature.

What do I mean by this? Tanaka, who had been a student of Shisei Tomita’s, was a free-spirited art teacher who instructed the likes of Nobumichi Ide (the plan to build the Contemporary Art Museum, Kumamoto, began with a donation to the city of paintings by Ide by surviving members of his family) and Chimei Hamada (one of the leading printmakers of the postwar era whose copperplate series “Elegy for a New Conscript” is particularly famous) at what was Mifune Junior High School (present-day Mifune High School). It was through this that a peculiar climate known as “the Barbizon of Kumamoto” was created in Mifune, something I first learned about in a lecture by Masatoshi Inoue, the former curator at the Kumamoto Prefectural Museum of Art responsible for such exhibitions as “All About Chimei Hamada” (2015) (and member of the Rescue Association executive office) given in conjunction with this exhibition. This climate reduced the distance between the townsfolk and oil painting on a daily basis, so while they may not have had a grand art museum, it led to them deciding they had to protect “those ‘treasures of Mifune’ by Kenichi Tanaka” that remained in local hands. If this were not the case, then how exactly would it have occurred to them to try to save paintings by one artist from a destroyed studio just one month after the disaster at a time when they themselves were struggling to secure food, clothing and shelter?

However, the emotional turmoil must have been far from ordinary. In fact, after seeing the paintings that had been left exposed to the rain and were covered in mold, ceramicist Hidekazu Watanabe (representative of the Rescue Association), a central figure in the rescue effort, commented in a newspaper interview that “Tanaka-sensei conveyed [through his paintings] the beauty of things that perish. The thought crossed my mind that we should leave them as is.” (2) One of the styles that characterizes Tanaka’s paintings is his depiction of wooden fishing boats abandoned in sea off Amakusa amid the changes of a harsh, irreversible natural world. Following the earthquake, Tanaka’s paintings themselves were now destined to perish, as if giving form to the thing that he most wanted to convey. The more people understood the essence of Tanaka’s paintings, the more pressure they must have been under to decide the best course of action.

However, according to Watanabe, “The contradictory desire to save [Tanaka’s paintings] in order to convey their aesthetic arose in me,” and this along with the desire to restore the paintings that were regarded as simply beautiful to their original state because they were beautiful paintings suggest that his awareness had reached a completely different dimension. Even if they are restored, the saving of Tanaka’s paintings depicting things falling into decay will represent not the restoration of ordinary beauty, but nothing more than the recovery of the appearance of “things decaying.” However, this appearance does not represent things simply put back the way they were. At this time, the strong impression viewers gain by way of the paintings will likely not be limited to simply the way “things decay.” Rather, it will reach as far as their self-awareness by prompting them to ask exactly what “things decaying” means. A way of viewing art that is not so much “appreciation” but rather something that can be called “reflection” will arise by way of Tanaka’s paintings that at one point really did “decay.”

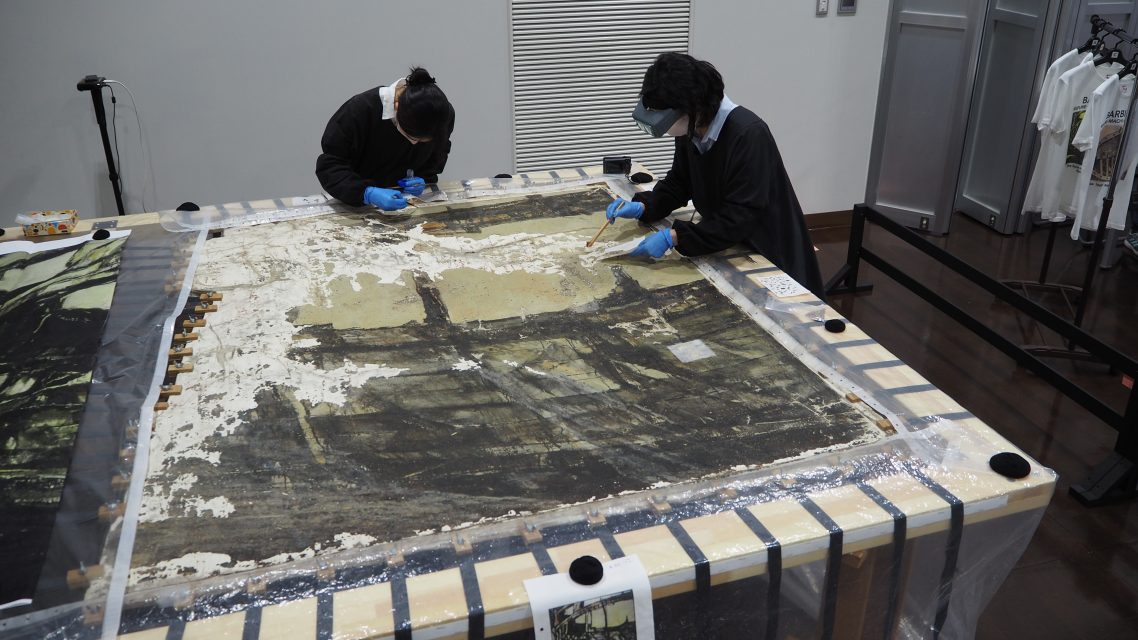

Restoration work performed live by Kikuko Iwai and Kie Iwai at “Art Doctor in Town.” Photo courtesy Iwai Art Conservation Laboratory.

Kenichi Tanaka – Umi no mukuro B (1967), (after restoration). Photo courtesy Iwai Art Conservation Laboratory.

So what about the exhibition? In addition to 13 paintings by Tanaka, of which six had been completely restored, it included displays of the tools Iwai uses and video of her working on previous restoration projects. As well, inside a roped off part of the gallery, Tanaka’s monumental Umi no mukuro B was raised off the floor and spread out like a trampoline while Iwai and her assistant, Kie Iwai, silently moved their hands like surgeons at an operating table performing a series of meticulous operations. Tanaka’s painting, which had endured an earthquake before being exposed to the weight of a collapsed house and the elements, was badly damaged to the extent that around a third of it was missing, giving it the appearance of a monster missing half of its body. Looking at it, I understood that this job is far removed from “restoration” in the sense of dealing with long-term deterioration. There were too many pieces missing to restore Tanaka’s painting, which had not deteriorated but “fallen victim to a disaster.” So can we really call Iwai’s job here “restoration”? Isn’t it more like reconstruction or even reproduction? Then again, we cannot afford to wait until we can answer this question before acting. Because in the years ahead there will be increasing demand all around us for such restoration work in the wake of disasters. At that time, we will have to consider what we regard as restoration, how much of a remaining work is the main body and to what extent it is permissible to “reproduce” missing parts on a case by case basis as we proceed with the work itself. If the artist is still alive, this may come close to “re-creation.” However, in cases like this one where the artist is absent, such a term cannot really be used. Despite this, the work itself comes quite close to the realm of re-creation.

When it comes to dealing with such difficult problems, the introduction of new technology will likely become important. In restoring the paintings by Tanaka that were damaged in the Kumamoto disaster, for example, Iwai is making full use of photographic records that survived. And by this I mean more than simply using them as visual references as she works. Images of the paintings have been digitized and enlarged and used to create hybrids, as it were, of the original pieces that are used as templates for the restoration work, on which basis the sense of scale of the originals can be restored while the work is being done. Looking at such scenes, one can appreciate how restoration of course brings together scientific knowledge and techniques, but at the same time involves applying a kind of generous imagination. I don’t want to overemphasize this, but in this sense I feel some connection between this exhibition and the work of Fumiaki Aono, who uses his imagination to supplement/repair missing parts of familiar objects that have been physically lost and re-creates/creates them as “sculptures” that appear to have existed somewhere but did not actually exist anywhere, or the Osamu Kofuku Engine in the Water Recreation Project (see Notes on Art and Current Events 69), in which those left behind following the death of Osamu Kofuku transported his Engine in the Water into a future that may have been but probably was not while discussing it from various angles. By their very nature, restoration and creation ought to be, or rather must be, contradictory acts. However, amid such new kinds of imagination, creation and restoration enter into a hitherto nonexistent loose relationship, forming a hitherto nonexistent field of art that lies somewhere between creation and technology, or between art and engineering. Looking at how the display of oil paintings and their restoration are not only conducted simultaneously but blend through the coming together of people involved in both fields at exhibitions like this one, the possibilities of such endeavors also suddenly enter my consciousness.

Scene from the talk event “Kenichi Tanaka and ‘Mifune, the ‘Barbizon of Kumamoto’” held on October 26 in conjunction with the exhibition. From left to right: Moderator Shinji Saito (Okayama University), Hidekazu Watanabe, Jun Taketazu, Masatoshi Inoue (Kumamoto Earthquake Kenichi Tanaka Painting Rescue Association). Photo courtesy Kumamoto Earthquake Kenichi Tanaka Painting Rescue Association.

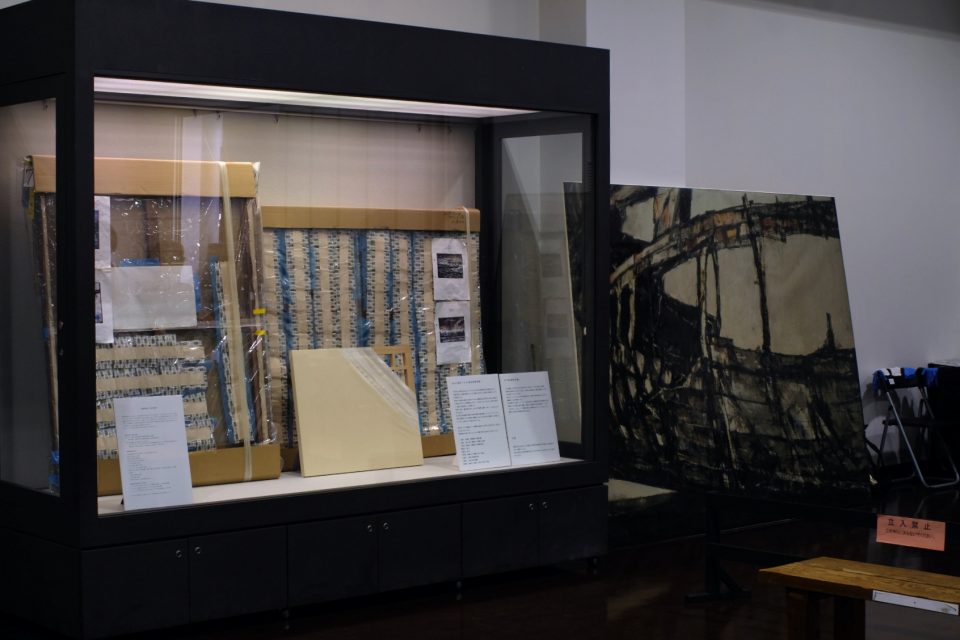

Deoxidation sealing display at “Art Doctor in Town.” Photo courtesy Kumamoto Earthquake Kenichi Tanaka Painting Rescue Association.

Another new technique Iwai is introducing at this exhibition is “deoxidation sealing.” This is not a technique for physical conservation itself, but as long as conservation and preservation are two sides of the same coin, the former will always be a race against time. In short, conservation is the art of defying the passage of time. If this is the case, in order to resist the passage of time, the thought of prolonging the passage of time is naturally a possibility. Even if this is not the case, in Japan the number of experts with the necessary skills in conservation is far from sufficient. Deoxidation sealing creates a temporary suspension of time so that damaged paintings can benefit from such a chance. It is a technique that involves spreading a deoxidizing agent over the surface of a painting and sealing the entire work to slow down as much as possible the speed at which the painting oxidizes. Or for paintings damaged in natural disasters, perhaps it could also be called a temporary and minimal level mobile storage room.

Of course, this is a stopgap measure. Once a painting is covered in mold it needs to be fumigated, and if it is immersed in water it needs to be adequately dried. But looking at cases such as the Kawasaki City Museum, not only conservation itself, but allowing enough time to get to work on conservation is extremely significant in a disaster. According to recent media reports, with regard to its future handling of the works in the Kawasaki City Museum’s collection, Kawasaki City officials stated that “because the works on paper in the collection affected by the disaster were immersed in water mixed with various bacteria, there is a chance that mold will continue to spread. To prevent this they need to be stored in cold conditions, which in this case means we intend to install a refrigerated container inside the facility to temporarily store the works after they have been frozen.” (3) The reference to “frozen storage” in a container inside the premises immediately called to mind the massive frozen earth wall I saw at the site of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident. Though not on the same scale as Fukushima, freezing the works will use a considerable amount of electricity. Doesn’t this bring with it fears of a power failure? This small exhibition held over just nine days by volunteers in the Kumamoto disaster-affected town of Mifune gave viewers a lot to think about regarding the intersection between natural disasters, the history of the local area and postwar art history, and the role of new collective wisdom and imagination in the latest conservation techniques and art.

1. “Typhoon 19 causes damage to libraries in 13 prefectures. ‘Items can be restored even if wet.’ Appeal for conservation,” Tokyo Shimbun, morning edition, October 28, 2019. [In Japanese]

2. “‘Treasures of Mifune’ restoration work continues,” Kumamoto Nichinichi Shimbun, October 21, 2019, p. 4 (Culture). [In Japanese]

3. “Flood damaged old documents to be put in frozen storage. Mold prevention measure by art museum in Kawasaki,” Asahi Shimbun Digital, November 16, 2019. [In Japanese]