Evading Perspective – Thoughts inspired by “What If AI Composed for Mr. S?”

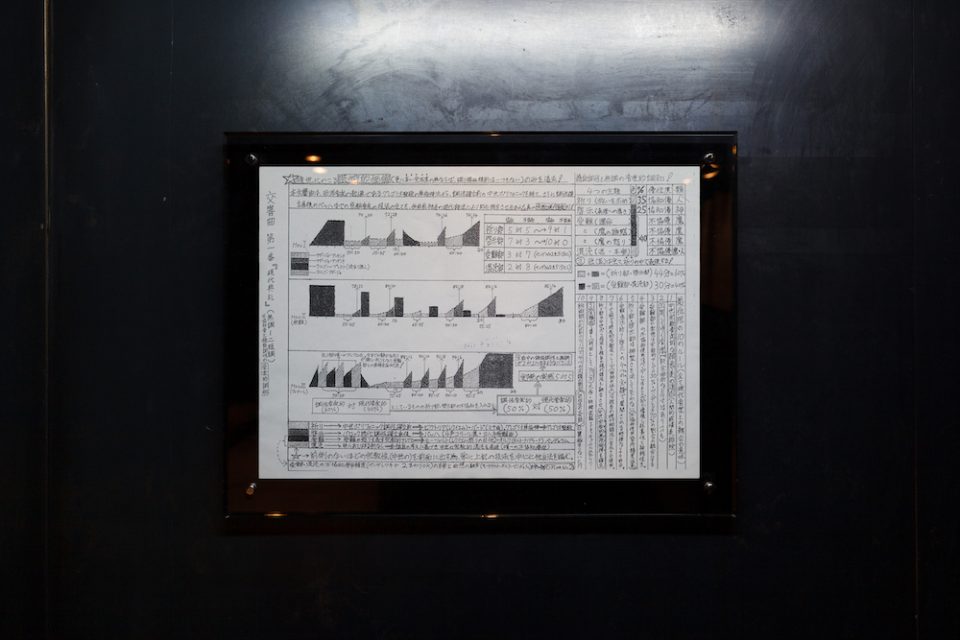

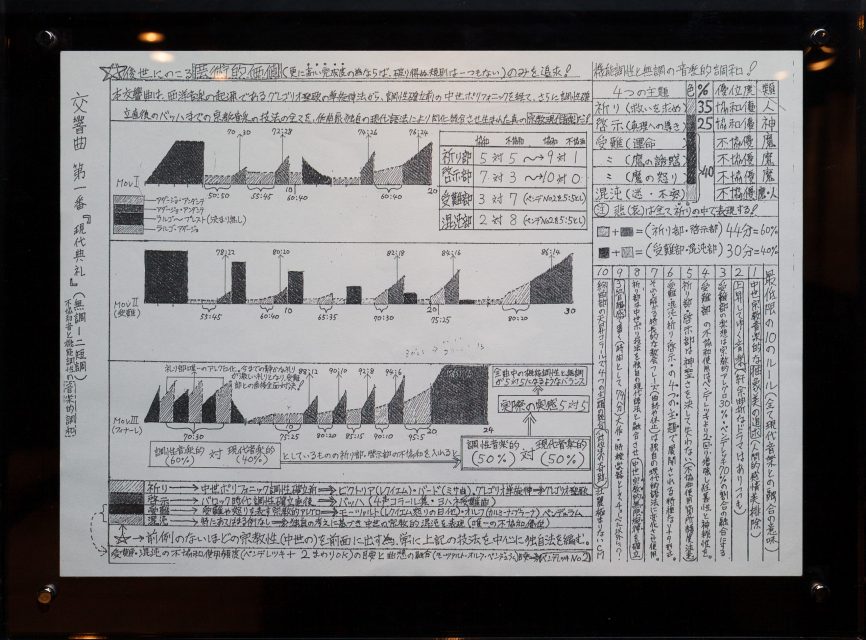

Reference material: Copy of an instruction sheet given to Mr. N by Mr. S (2014), photocopy on paper, 21 x 29.7 cm. From the Artificial Intelligence Art and Aesthetics Research Group exhibition “What If AI Composed for Mr. S?” All images: Masaru Kaido.

Recently, time seems to pass incredibly quickly, in what is perhaps another secondary effect of social media. Incidents, accidents and other events are forgotten one after another as soon as they are reported, and even though some of them are extremely significant in historical terms, they are all consumed in a like manner without being particularly closely examined. I cannot help feeling more than a little uncomfortable at this state of affairs. Events such as the uproar that arose suddenly like a whirlwind after it was revealed and reported in 2014 that a work attributed to composer Mamoru Samuragochi had been ghostwritten by another composer almost seem like occurrences in the distant past and are not especially recalled today. In fact, the reason my attention was recently drawn again to this episode, which I had completely forgotten (meaning that, despite the fact that I just wrote that I cannot help feeling uncomfortable at such things, even I cannot resist the speed of forgetting these days), is none other than that I got the chance to see “What If AI Composed for Mr. S?,” a show being held by the Artificial Intelligence Art and Aesthetics Research Group (AIAARG) at The Container, an exhibition space in Tokyo’s Naka-Meguro/Daikanyama district.

While his name is kept secret with the use of an initial, based on the context, it need hardly be said again that Mr. S is the above-mentioned Mamoru Samuragochi. However, the question raised from the AIAARG’s standpoint is different in nature from what might be revealed if one were to try to rehash the scandal. It is because the composer who was secretly asked by Samuragochi to ghostwrite the work in question was another, actually existing composer by the name of Takashi Niigaki (like Samuragochi, in the exhibition he is referred to using an initial as Mr. N) that the situation developed into a major problem, so the question AIAARG posed was whether it would have caused such an uproar if the work had been ghostwritten by an AI without a human-like personality. My immediate response to this is that opinion is probably divided within the various specialist fields, including the legal field encompassing copyright and moral rights, ethics and cognitive theory, and of course the latest AI research, and because it is not the kind of subject usually covered by art criticism, I will refrain from commenting further here. However, this is an exhibition planned by a group that deals primarily with art and aesthetics, so I would like to respond to it from the standpoint of art criticism.

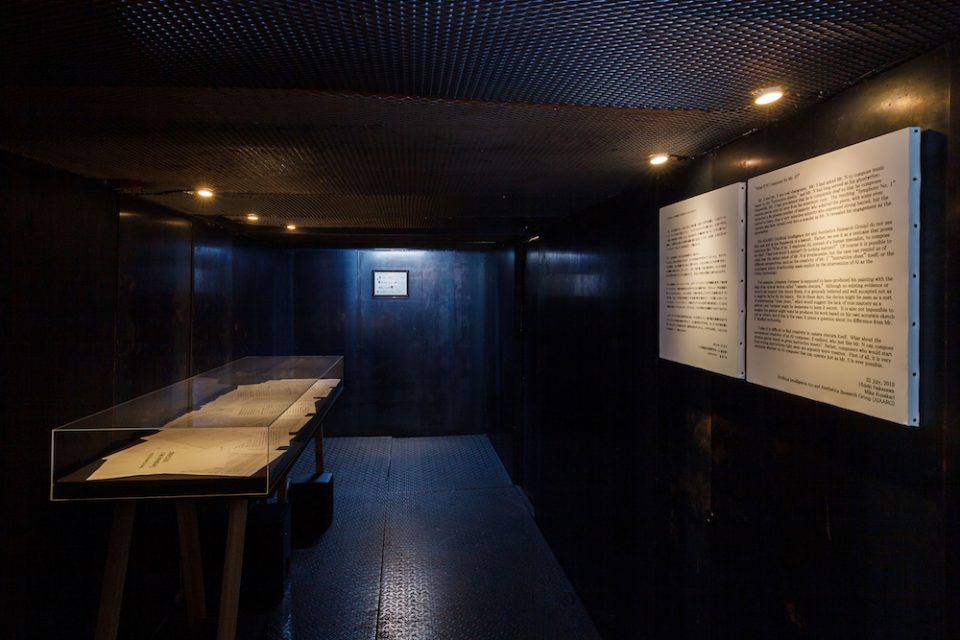

Installation view of “What If AI Composed for Mr. S?”

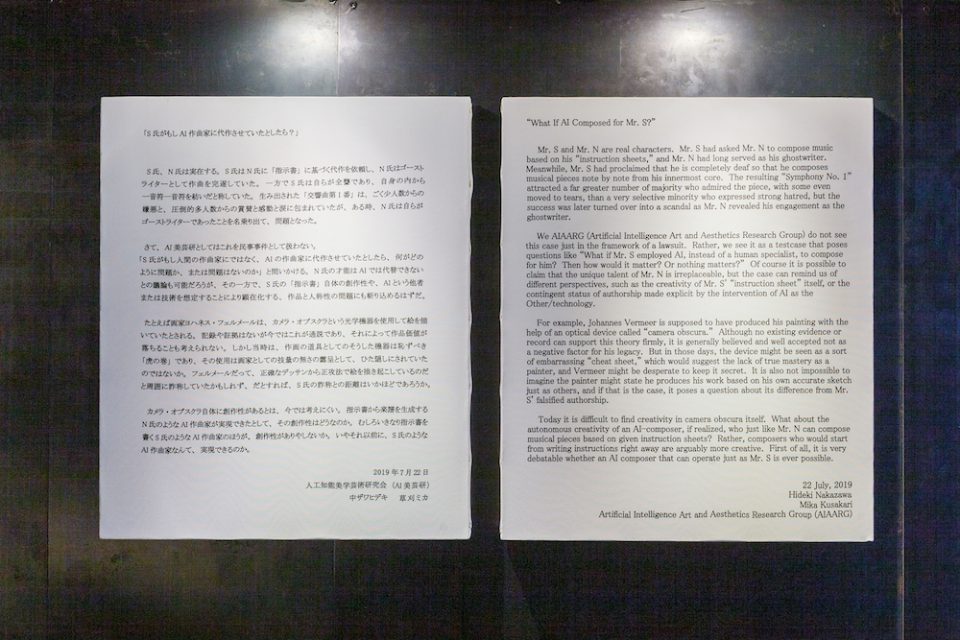

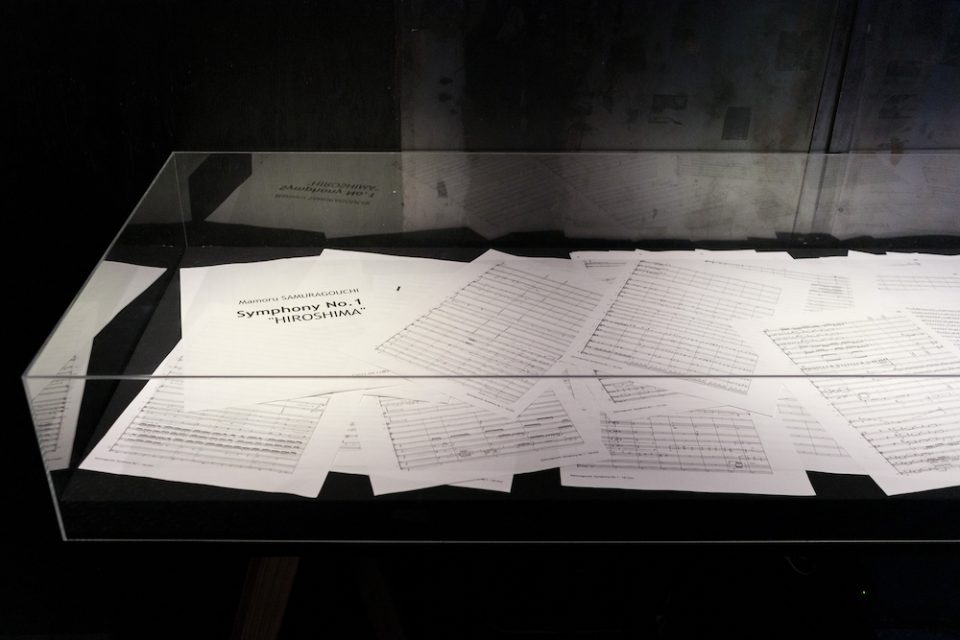

First, let me describe the venue. The exhibits are presented inside an actual container installed in a corner of a beauty salon, and there are just two two-dimensional pieces (ink on canvas) displayed side by side on a wall and titled Work-J (2019) and Work-E (2019) that are identified as works by the AIAARG. Printed in Japanese (J) and English (E) respectively on the surfaces of these works are written explanations of the aims of the exhibition (dated July 22, 2019 and signed by the Artificial Intelligence Art and Aesthetics Research Group (AIAARG) as well as Hideki Nakazawa and Mika Kusakari), parts of which are also printed in the catalog with the same title published to coincide with the exhibition. Visitors can also view other items including an instruction sheet said to have been given to Niigaki by Samuragochi when requesting the ghostwriting and the score for Symphony No. 1 “Hiroshima,” Samuragochi’s most famous and grandest work, but these are not works by the AIAARG and are treated as material supplementing the above-mentioned two pieces. As well, Symphony No. 1 is played at the venue using a sound source that appeared on the market. Overall, the visual elements are few in number and the exhibition space is tiny, but apart from this, special mention also probably needs to be made of the fact that adjoining the venue is the Naka-Meguro Daikanyama Campus of the Tokyo College of Music. In fact, through the glass in front of the venue, young people carrying musical instruments can be seen here and there walking along the sidewalk, some of whom may perhaps be aiming to become composers like Niigaki. As it happened, the exhibition has turned into a “site-specific” display.

Artificial Intelligence Art and Aesthetics Research Group – Work-J (left) and Work-E (right) (2019), ink on canvas, 45.5 x 38 cm each.

Upon entering the venue, the first thing that surprised me was that the “instruction sheet” that Samuragochi gave to Niigaki did not resemble an ordinary “instruction sheet,” but rather it had the air of an “artwork” about it in that it resembled a drawing. The next surprise was that this exhibition afforded me the opportunity to confirm with my own ears for the first time exactly what kind of music the resultant Symphony No. 1 “Hiroshima” was, given that despite all the uproar I had never actually had the chance to listen to it.

Regarding the latter, after viewing the exhibition I bought the CD and listened to it again a number of times. Appealing aspects in the form of what could be called the essential points of Western musical history are in fact cleverly distributed throughout it, and while it lacks newness, as a symphony it is extraordinarily well composed. This goes some way to explaining why, even though he himself revealed at a news conference that he had been contracted to do the ghostwriting and was widely punished in social terms, Niigaki’s standing has not fallen since the uproar and he continues to work to this day. One could say this is in complete contrast to the circumstances of Samuragochi, who in order to distinguish himself as a composer professed to be totally deaf. Despite this desperate adversity that extended from when he was young to the present, he also professed to have completed a symphony by drawing on the desire that remained shining like a light inside of him to the end, shortening his life by writing down each sound individually on paper. In fact, he is not totally deaf. What is more, it is said that he cannot even write music, and the “adversity” he wrote about in his own work has also been revealed to be a case of over-dramatization. His whereabouts are currently unknown.

But to get to the bottom of this affair, it originates from the fact that in the background to this remarkable outcome there existed a skillfully fabricated “story” in which a “highly gifted composer” who found himself in such unfortunate circumstances overcame one difficulty after another to complete and make public a symphony on a par with the works of Beethoven, Brahms and Mahler in the Far East, far removed from the center of classical music. Because wasn’t it a fact that before questions arose as to whether it was untrue or not, the thing people went completely wild with excitement about was this story that formed the background to their listening to the music? It is not as if – before looking for who was to blame – the very fact that such a story was so widely sought went away, even after the uproar. To put it another way, Samuragochi’s fall was also the result of a huge “disappointment,” and there was no criticism or comprehensive casting of doubt on the inclination itself to seek these kinds of stories. In other words, even if Samuragochi’s reputation declined, one could probably say that the story itself that supported this reputation still survives unscathed. We can get something of an insight into this in the “instruction sheet” said to have been given to Niigaki by Samuragochi, in which the latter set out in a peculiar format his almost bizarrely specific expectations. Because the sheet contains things that are essentially different from what you would expect to find in a simple business “transaction.”

Reference material: Instruction sheet given to Mr. N by Mr. S (2014), photocopy on paper, 21 x 29.7 cm. A reproduction of the “Symphony No. 1” instruction sheet that Mr. S sent to Mr. N at the end of 2001 (estimated); one of the actual copies distributed by Niigaki at a press conference held on February 6, 2014, in the Edo Room of the Hotel New Otani.

Reference materials: Installation view of the symphony score ghostwritten by Mr. N for Mr. S, photocopy on paper, 29.7 x 42 cm, 243 sheets. The entire score of “Symphony No. 1,” ghostwritten for Mamoru Samuragochi by Takashi Niigaki, referencing Samaragochi’s instruction sheet, from late 2001 (estimated) to early 2003. (April 11, 2011 edition)

Something I find interesting from a different angle is that at the time of the uproar in 2014, despite such an emotional story already having been widely disseminated, I personally had had no opportunity whatsoever to encounter either Samuragochi’s name, his compositions or his story. Considering that Samuragochi’s “story” had progressed to the point where one of his pieces was going to be used by a Japanese figure skater at the upcoming Winter Olympics, isn’t this somewhat strange? Considering also that Nakazawa himself touches on similar thoughts in the study (coauthored with Kusakari) included in the exhibition catalog, it seems unlikely that I am alone. Nakazawa and Kusakari link the presence of Samuragochi in the Japanese music world to, and suggest parallels with, the problems surrounding Hiro Yamagata (previously also raised by Nakazawa himself) as well as illustrators such as Christian Lassen. In other words, it is possible that, despite having huge influence and capturing the hearts of the masses, his was an awkward presence that as far as the art world was concerned was a blind spot or something they had decided to ignore.

But from where did such avoidance and ignorance of national emotion and popularity by the art world originate? When it comes to art, answering this question is not especially difficult. The modernization of art was achieved by regularly eliminating from artworks the kind of narrativity epitomized by the Romantic and Neo-classical art of the 19th century. To put it simply, because dramatic elements such as narrative are not among the purely visual problems art deals with, but essentially belong to the fields of literature and theater, in order to produce artworks in a way that is faithful to the genre’s properties, these elements would naturally have to be eliminated as obstacles. Not being able to sense popular emotion or narrativity from modernist painting or sculpture is an extremely proper procedure, and one scarcely need raise the examples of Cezanne or Pollock’s paintings.

Contemporary art, which is an extension of modern art, is no exception. When we sense that we have viewed a work that easily appeals to the kinds of emotions that are seen as interference in visual art or the narratives that underpin them, it seems that we can see the work but in fact we cannot see it at all, because such experiences are not at all autonomous. Creating the kinds of places where we can experience artworks autonomously is itself an important theme concerning art, which is to say, exhibits in which patronizing narratives are cut to the utmost, so that one can put oneself in the exhibit voluntarily, and in which unless one makes an effort to acquire subjectivity, one doesn’t understand the work are rated preferentially as art, be the works paintings or some other form of art. On the other hand, one can also view this approach as being underpinned by a somewhat moribid rejection of excitement, emotion or narrativity.

Because in the case of Japan, potentially adding fresh fuel to this rejection is the problem of war paintings. Pre-war Japanese modernist art had achieved a high level even by international standards. However, once the militarists appeared and started pushing the people towards war, to boost national prestige, art, too, was required to take on the function of providing harmonious “emotion.” Far from being eliminated, emotion and narrativity were willingly incorporated into artworks in order to hide the truth and to encourage people to serve the country even if it meant risking their lives. If we take the post-war period as the starting point for serious reflection on such “indiscretions,” then it is probably natural that people are wary of the tendency to seek powerful emotions or narrativity in art. Leaving aside cases involving commercial culture (entertainment) such as film and popular music, for pure artistic acts that must seek the measure of their worth in historical dialectic proof, powerful emotions and narrativity must naturally become things that are guarded against to the fullest extent possible. Behind my, Nakazawa and Kusakari’s failure to know even Samuragochi’s name and the art world’s neglect of people like Yamagata and Lassen can be seen such historical circumstances concerning art, as well as a dissociation concerning popular acceptance. However, as long as artists are involved in “creating things” in any sense at all, regardless of how hard they try to suppress it, the strong desire for expression that stirs such grand narratives or emotions never completely disappears.

For example, the equivalent in art to the symphony, which could be called the quintessence of classical music, is probably the large-scale oil painting (not paintings in acrylics, and certainly not large-scale installations!). However, I do not mean just any oil paintings. Like the paintings of Delacroix and Géricault (and like the symphonies of Beethoven and Brahms?), they must be skillful depictions of groups of figures that capture in one fell swoop dynamic scenes in which multiple elements intertwine, or in other words tumultuous moments in history. War paintings are perhaps the perfect example of this. In fact, because the army’s Captain Ichiro Yamanouchi, who recommended artists be sent to the front during the war and decided where they would be sent and what they would be commissioned to paint, enjoyed painting when he was young, he long harbored feelings of shame at how little painters contributed to society. Furthermore, he saw war paintings as concrete expressions of the historical and glorious achievements of the military that any ordinary person could understand and, on condition that they were rendered on large canvases using oils, he advocated them as a means of communicating forever to later generations the great achievements of the people, something that could only be realized through painting. It is probably for this very reason that Yamanouchi entrusted this task to the elite of the art world. No doubt it was because he himself had knowledge of painting that he understood that, though they were inexperienced and would therefore struggle to a small degree, if they tried they had the ability to soon start producing war paintings in the same way they produced the nudes, landscapes, portraits and still lifes they made their names painting before the war.

To put it another way, Japanese painting, which in the Meiji period imported the technique of oil painting as a ready-made method in imitation of the West, was not founded on “thought.” Or perhaps it had gained “spirit.” But thought is a product of history. And though it may sound like a strange way of putting it, the history of Japanese art beginning in the Meiji period has nothing corresponding to an essential history. Putting it the other way around, that Japanese artists were able to acquire “spirit” as individuals in the Taisho period may be because history, which already exceeds the individual and exists collectively and cannot be changed, was not there to hinder the expression of their inner spirit. To use the AIAARG as an analogy, it is as if they were like protean “AI composers” devoid of thought that, as long as they were provided with the relevant input conditions, could produce the corresponding results. Furthermore, for the Japanese, who had embarked on a fresh start into the unknown in the Meiji period, one could say that the format of oil painting from which oppressive history had been extracted represented these very AI-like input conditions. The artists of this period solved this problem brilliantly. However, they produced not paintings as manifestations of thought, but paintings as expressions of spirit. Or perhaps, as happened as the Taisho period transitioned into the Showa period, they might as well have completely removed spirit along with everything else. This would have enabled painting to be more successfully resolved into technique and form. In fact, in the realization before the war of abstract and surrealist painting, there is no small amount of this type of thing. Even though their subject matter and methods may have been different, before long the situation with regard to the state gave them no choice as to what they could depict. However, that did not bother them. By then, oil painting had already become a question of inputs and outputs. The artists who produced war paintings were truly the descendants of this. And for this very reason they were able to suddenly switch from nudes and landscapes to producing historical groups of figures, and then return after the war to nudes and landscapes as if nothing had happened.

In fact, the military sent letters of appointment to influential figures in the art world and the painters that received them were sent to the front as war artists, where they used various materials provided by the military and were also provided with subject matter in the form of instructions to paint such and such a battle scene, so that many war paintings were completed in a way that reflected this state of affairs. In a manner of speaking, they were working based on “instruction sheets.” And so after Japan lost the war, some war artists refused to discuss these works, saying they had been made to produce them in accordance with the military’s wishes and that they were not really their own work. However, there is no essential contradiction between whether or not one recognizes a work as one’s own, and whether or not one has the (AI-like) ability to produce uniform results in accordance with an instruction sheet that has been provided. With regard to this exhibit, the only difference is whether as an initial condition there is a “story” about a historic masterpiece created in the face of considerable hardship by a totally deaf genius, or a “story” about how, on reflection, Western modernity was “overcome” by the military who liberated Asia from the oppression of the Western powers during the war. Of course, leaving aside the difficult question of who the real creators of these war paintings were (just as similar questions are left aside in this exhibition), as rewards the war artists also secured famous “honors” including the Imperial Art Academy Award. And underpinning these honors was not the power of the individual works themselves in a modern sense, but the moving stories at the national level of fighting through to the end of the Great East Asia War.

Behind reinstated modernist art’s efforts to seek artistic consummation after the war by eliminating stories and emotion from the background of its works, by being wary of feelings and by avoiding mass popularity was this kind of rational apprehension. However, as already mentioned above, even after Samuragochi’s lies were exposed, it was not as if the doubts that were raised extended to the mass mentality that seeks emotional stories. Similarly, the reconsideration of propaganda art was born out of a “backlash” against art that evokes emotion or stories, and the mentality that seeks such emotions and stories in art is as constant as ever. If anything, the more we try to intentionally suppress it, the greater becomes the danger that this unconscious desire suddenly gets another opportunity via a different route and bursts forth from some unexpected place. This is not just a problem for the recipient. In fact, the creatives that were absorbed in modernist art that was in principle ascetic cooperated in the production of war paintings for other reasons in addition to their being forced to do so. As was the case with Tsuguharu Foujita and Saburo Miyamoto, there were some who thought that the right path of art history in places like the Louvre lay in paintings of historical events, and that having become aware of the extent to which Japanese art history had become trivialized into the memoir-like everyday, they had been given a golden opportunity to at last be involved in “real art history” as artists. Can we really say positively that Niigaki, who had been confined to the world of contemporary classical music where both audiences and opportunities to present work are limited, was not prompted by similar motives in being unable to resist the temptation of a “symphony” that might enable him to be directly involved through Samuragochi in musical history?

Which reminds me, while it may sound somewhat sudden, if we put these matters in our minds, we need to take notice of the fact that amid the series of disturbances surrounding the “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” exhibit at the Aichi Triennale 2019, which was forced to close down after just three days due to the presence of that statue of a “girl of peace,” speaking on behalf of the government, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga quickly made two remarkable statements. The first was on August 2 during the morning post-cabinet press conference, when in response to a reporter’s question he said, “Concerning the granting of subsidies, I would like to respond appropriately after ascertaining and examining all the facts.” One cannot go as far as saying for certain that this statement itself is something that directly arouses pressure on expression, and if one interprets it sympathetically it goes no further than re-confirming the extent of Suga’s authority by virtue of his position. But if one understands this statement in tandem with the contrasting statement reported as also having been made by the Chief Cabinet Secretary on August 19, the situation becomes somewhat different. Suga, who on the same day inspected the teamLab exhibition currently being held at Odaiba, noted, “This kind of participant experience, enjoyment and intelligibility. Such elements will become necessary from the standpoint of Japanese tourism aiming to go a step higher,” before emphasizing, “I would like to further deepen this initiative.” If we consider the two together, it is the same as saying that in making decisions regarding the granting of subsidies involving art and culture, he wants to make initiatives involving art endowed with “participant experience, enjoyment and intelligibility” the standard for close examination and further promote them. Doesn’t this appear to overlap somehow with Captain Ichiro Yamanouchi’s championing during the war of the benefits not of unintelligible abstract art or smug avant-garde art but of painting that is easily understood by the masses and of value to the state? In this sense, despite Samuragochi’s fall, one could say there is an increasing demand for “mobilization art” that evokes national emotion and stories. To return to the beginning of this essay, it is precisely because the muddy waters of time in which information is consumed uniformly are directly before our eyes that we need to ensure not only that are we not sucked in to these waters, but also where the current itself is heading now and our own precise whereabouts. The AIAARG’s exhibition “What If AI Composed for Mr. S?” evades the perspective of history, hurdles scandals, and suddenly deposits at our feet such disquieting questions.

Note: The remarks made by Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga are based on what was reported in various Japanese news media.

The Artificial Intelligence Art and Aesthetics Research Group (AIAARG) exhibition “What If AI Composed for Mr. S?” was held at The Container in the Naka-Meguro/Daikanyama district of Tokyo from July 22 to October 7, 2019.