Criticism and Assessment: Concerning Art Concerning Disability

Installation view, “Meguru a–to wo meguru” at Kyoto-ba, Kyoto, 2019. Photo Atsushi Ueyama.

Installation view, “Meguru a–to wo meguru” at Kyoto-ba, Kyoto, 2019. Photo Atsushi Ueyama.

Over the past few years, I’ve often been asked to comment on the relationship between disability and art. Just the other day, I spoke at an event held in conjunction with “Meguru a–to wo meguru” (Kyoto-ba, Kyoto), an exhibition staged by Tanpopo-No-Ye, a nonprofit organization that organizes activities in Nara Prefecture aimed at promoting art and culture among people with disabilities. (1) My work being what it is, I’ve spoken about various things at art museums over many years, but only rarely have I encountered an overlap – be it in the people contributing the artworks or the people supporting the event – in exhibitions of these two ilks. This stems from the fact that it is the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare that has responsibility for “disability” at the national level, so its axis is removed from “education,” which is covered by the Agency for Cultural Affairs and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, which deal with bijutsu (fine art). Art involving people with disabilities falls primarily under the category of “welfare” as opposed to education. Based on my own personal experience of raising children, the easiest way of understanding this might be to compare it the difference between a school (preschool) and a day-care center (nursery).

A school is an educational institution, but a day-care center is a childcare facility, which is basically a place that takes responsibility for looking after young children for a fixed period of time because the parents are working (and a service to which I am greatly indebted). Accordingly, whereas at school there are “assessments,” or in other words “results,” hanging over the learning achievements of children, at day-care centers there are not. If children at each drew pictures, for example, at the former they would be subject to assessment to determine their relative merits, while at the latter they would all be treated as equal. In the end, this presents itself as the difference between the well-regulated atmosphere of schools where the importance of order is stressed and the somewhat anarchic ambience of day-care centers (though if I were asked which one I preferred, it would undoubtedly be the anarchic one).

Taro Okabe (right) of Tanpopo-No-Ye and the author (left) speaking at the “Meguru a–to wo meguru” exhibition-related 3rd Seminar for Considering the “Mediation” of Art by People with Disabilities: Considering Assessment (February 7, 2019).

Taro Okabe (right) of Tanpopo-No-Ye and the author (left) speaking at the “Meguru a–to wo meguru” exhibition-related 3rd Seminar for Considering the “Mediation” of Art by People with Disabilities: Considering Assessment (February 7, 2019).

In light of the above, if I were asked why someone like me – a complete amateur when it comes to welfare – is regularly invited to welfare-related events, one reason I could give would be that these exhibitions, while relating to welfare, actually take the form of social projects open to people outside the facility concerned. To the extent that they are open, there is naturally a demand at these places for such value notions as (worthy of) “appreciation” and (worthy of) “assessment.” However, unlike in the case of “works” that are created as bijutsu from the outset, it is difficult to assess or determine individually the relative qualitative merits of things that are above all the result of welfare-like support. To say nothing of the fact that there could hardly be people more reluctant to publicly assign relative merit to “expression” created by individual users of facilities than the people dedicated to providing welfare, which, given the definition of the word, involves a commitment to equal opportunity. This is the kind of background that needs to be considered when discussing the reason why “critics” like myself are being invited to events such as the above. In other words, How on earth do critics “assess” artworks to begin with?

The title of the exhibition in Kyoto, “Meguru a–to wo meguru,” also perhaps derives from this question. This title, which could be translated as “Concerning concerning art,” seems to allude to the tossing around of such meta-labels as “an x concerning art concerning disability,” or in terms of the topic of this column, it could also be interpreted as the condensation of such circular arguments as “. . . concerning assessment concerning art concerning disability concerning art concerning assessment concerning art concerning disability . . .” One could say it is an extremely frank title reflecting the kinds of scruples one would expect to find in people in charge of such sites. As an attempt to share widely through the concept of an exhibition such questions that are quite difficult to visualize from the sites themselves, this exhibition had great significance.

Installation views, “Meguru a–to wo meguru” at Kyoto-ba, Kyoto, 2019. Photos Atsushi Ueyama.

Installation views, “Meguru a–to wo meguru” at Kyoto-ba, Kyoto, 2019. Photos Atsushi Ueyama.

But this still leaves the question of how best to respond. Without thinking about it too deeply, my initial response would be that the countermeasures are surprisingly simple. One need simply apply the assessment standards for fine art works that are the existing standards according to the criteria prescribed by the state. In which case it should even be possible to assign scores. In fact, the school system has followed this example in uniformly “assessing,” “recognizing” as results and judging for the purposes of “advancement” or “graduation” bijutsu-like expression that is not really compatible with assessment to begin with. However, there is nothing as difficult as far as art is concerned as applying such a mechanical educational notion. For reasons of convenience, I have so far distinguished between bijutsu and art, the former being a concept officially approved by the state (in the same way that bijutsukan, meaning “art museum,” and bijutsu daigaku, meaning “art university,” are), while the latter has authenticity on account of the lack of such an endorsement. The former is a part of education and in this sense its assessment as a deliverable is also entirely possible. However, the latter, ie, “art,” is fundamentally incompatible with “assessment.” Because inherent values cannot be assessed. In which case it would be more accurate to call it “expression.”

But who on earth can “assess” individual expression? Is it even possible to systematically apply numerical values to the diverse expression in compelling forms that arise from each individual’s unique circumstances? There is no way this is possible. This being the case, whereas bijutsu is an educational concept, if anything (and particularly in respect to its anarchic qualities) art is closer to a welfare concept in the sense that it is difficult to assess uniformly, is offered to everyone on an equal opportunity basis, and is equal as a mutual relationship.

This relationship between bijutsu and art in fact corresponds to the difference between assessment and criticism. In essence, criticism is not assessment. Because the aim of criticism is that when trying to assess the object before one’s eyes as a “work,” value notions that are regarded as self-evident as fixed standards are shaken through the use of words. In this respect, “bijutsu/education/assessment” and “art/expression/criticism” are largely antagonistic to each other. For this very reason one could say that the real potential of education dealing with bijutsu lies in its ability to deal critically with such subjects within the education system.

In this sense, it is perfectly acceptable for all criticism (including the artist’s words) to be impressionistic. The term “impressionistic criticism” is commonly used as an insult, but the most difficult thing to achieve in criticism is criticism that is personal and impressionistic and traces faithfully to the end the subjective impression one receives from expression and yet evokes a sympathetic response from large numbers of people. Words that involve predetermined, fixed values and the application of mechanical value judgments are in essence not criticism. Such an approach makes it impossible to surmount and relativize the latent value indexes that become barriers to all expression.

So this was the kind of thing I said during the exhibition in Kyoto, though I am not certain whether this was the kind of response most of the people gathered there were after. But in any case, at welfare sites involved with disability and art, there can be little doubt that there is now some confusion arising over value notions concerning the question of how to “assess” expression as a product of support, which is often at a level below “artwork” (or, to borrow a term used by Creative Support Let’s, the NPO that operates Ars Nova and other welfare facilities for people with disabilities in Hamamatsu, Shizuoka Prefecture, “expression or less”)(2).

As the background to this, the shadow cast by the Law Relating to the Promotion of Cultural and Artistic Activities for People with Disabilities, promulgated in June 2018, is considerable. To be specific, under the heading “Assessment, etc. of Works, etc. with High Artistic Value,” Basic Measures (4)-1 of the text includes the following:

1. The government and local public bodies shall develop an environment and take other necessary measures for the purposes of investigating the situation with regard to, and the specialist assessment of, works, etc., by people with disabilities so that works by people with disabilities with high artistic value receive the appropriate assessment. (emphasis added)

This means the sudden introduction into welfare sites of the value notion used in education. Moreover, there are no specific guidelines whatsoever concerning what kinds of works will be regarded as works with “high artistic value” or what form the “specialist assessment” will take. If anything, the inclusion in a supplementary resolution of the text, “in taking the measures stipulated in this law, when assessing works, etc. by people with disabilities, due consideration should be paid to ensuring division or discrimination do not occur as a result of this assessment as well as to ensuring the value of a wide range of works, etc. is recognized regardless of existing values,” (emphasis added) suggests that while concern is being shown regarding the disadvantages in welfare terms that might arise from mechanical value assessments, as long as no standards regarding what kinds of works are regarded as having “high artistic value” are indicated to begin with, there is no way of avoiding them being applied arbitrarily as the occasion arises.

An important thing to note in considering this matter is that the various relevant organizations were notified of this Law Relating to the Promotion of Cultural and Artistic Activities for People with Disabilities by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. In other words, while under this law art and culture are handled by the same agencies and ministries as before, at the same time, to the extent that the Agency for Cultural Affairs, which is responsible for education, prescribes people with disabilities as recipients of welfare, which is handled by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, it largely crosses the existing barriers between agencies and ministries. As a result of this, it is possible to apply transgressively the education notion of “assessment” to welfare concepts. And further along this road is the application of economic concepts. Because having a value notion is none other than having an exchange value based on consistent treatment. In other words, things whose value can be recognized can be bought and sold on the market on account of this value. Put more simply, a traversal from a welfare concept (support) to an education concept (assessment), and from an education concept to an economic concept (buying and selling) can be observed. Consider “(6) Support Regarding the Sale, etc. of Works, etc. That Have High Artistic Value,” from the same Basic Measures referred to above:

The government and local public bodies shall develop a system and take other necessary measures to support liaison and coordination with organizations dealing with people with disabilities regarding the planning and transfer of compensation in relation to sales, public performances and other business activities with regard to works, etc., by people with disabilities with high artistic value so that these activities can be conducted smoothly and appropriately. (emphasis added)

Furthermore, as a liaison and coordination body for the smooth promotion of these policies concerning art by people with disabilities, the Council for the Promotion of Cultural and Artistic Activities for People with Disabilities (1. Outline of the Law – 4) will be established. Clause (1) of the article reads as follows:

(1) The government shall establish the Council for the Promotion of Cultural and Artistic Activities for People with Disabilities comprising personnel from the Agency for Cultural Affairs, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and other relevant administrative agencies to carry out liaison and coordination to ensure the comprehensive and effective promotion of cultural and artistic activities for people with disabilities. (emphasis added)

In this way, not only educational concepts, but suddenly even economic concepts became mixed together in the field of expression by people with disabilities. From the perspective of welfare support enterprise workplaces, this is nothing other than an extremely significant change. Yet despite this, across all actual sites providing support to all people with disabilities, this law hardly makes any sense. This is because the “works” by people with disabilities targeted by this law are in essence regarded as things made by people with intellectual disabilities. Though this is not clearly stated in the text of the law, the text includes statements that could be interpreted this way. For example, “(2) Basic Principles 1 (a)” and “(b)” under “1. General Provisions” read as follows:

a. In view of the fact that creating and enjoying art and culture are people’s inherent rights, cultural and artistic activities for people with disabilities shall be promoted widely in order that citizens can appreciate, participate in and create art and culture regardless of whether or not they have a disability.

b. Artistic and cultural works that display creativity inherent to people and are not based on specialist education are rated highly, and based on the fact that most of these works are by people with disabilities, etc., support for the creation of works, etc. by people with disabilities with high artistic value shall be strengthened. (emphasis added)

For the time being, it is “b” that requires our attention. According to “a,” which has precedence in terms of the text of the law, the strengthening of support under this law ought to apply to all people with disabilities, but due to the presence of “b,” in essence this is limited to only some people with disabilities. Because in spite of the fact that it is clear that what is written in the first half of “b” follows the examples of “outsider art” and “art brut” (in the original sense of the term as coined by Dubuffet) in the West, the reality stated in the second half of the paragraph that “most of these works are by people with disabilities, etc.” is a tendency peculiar to Japan, and the fact that people with intellectual disabilities are responsible for the majority of these works is a well-established fact among people involved in this country. However, perhaps because stipulating this would go against the principle of equal opportunity with respect to support, by not actually insisting that it applies to people with intellectual disabilities in particular, and by adding “etc.,” room is left for interpretations in which the area of interest is not restricted.

However, if one thinks about it in more general terms, even if “[a]rtistic and cultural works that display creativity inherent to people and are not based on specialist education” are “rated highly,” affirming that “most of these works are by people with disabilities” diverges from reality even if the security of “etc.” is included. Because even looking at it historically, it is far from the case that the major pillars of outsider art and art brut are all people with disabilities. On the contrary, isn’t it true that the very fact that the possibility exists that perfectly “ordinary people” (for example workers and full-time househusbands/wives, retirees and the elderly, or children) can display such creativity the gist of the statement in “a” that “creating and enjoying art and culture are people’s inherent rights”?

If that were all, however, then it would be unnecessary to go to the trouble of bringing people with disabilities into it. Surely it would be possible to respond adequately under the Basic Law on Culture and the Arts (Article 22 of which mentions developing an environment and taking other necessary measures with respect to not only people with disabilities but also the elderly). For this reason, it is conceivable that the gist of “a” in fact lies not in the words “people’s inherent rights,” but in the words “regardless of whether or not they have a disability.” Because despite the fact that “creating and enjoying art and culture are people’s inherent rights,” the reality is that due to existing preconceptions and various barriers in our present society, opportunities for this to be sufficiently realized are not being provided. In this sense, that a law concerning culture and the arts focused exclusively on people with disabilities has come into force is highly significant. If any questions still remain, as noted above, they concern the opaqueness of the provisions around assessment and values in the text.

So, just what is the definition of “person with a disability,” which is surely even more fundamental in considering the above? “(1) Definitions” of “1. General Provisions” in the Law Relating to the Promotion of Cultural and Artistic Activities for People with Disabilities reads, “The term ‘person with a disability’ as used in this Law refers to a person with a disability as stipulated in Paragraph 1 of Article 2 of the Basic Law on People with Disabilities.” As to the question of who is covered by the term ‘person with a disability’ as stipulated in the Basic Law on People with Disabilities, the answer is as follows:

“Person with a disability” refers to a person with a physical disability, a person with an intellectual disability, a person with a mental disability (including developmental disabilities), and other persons with disabilities affecting the functions of the body or mind (hereinafter referred to collectively as “disabilities”), and who are in a state of facing substantial limitations in their continuous daily life or social life because of a disability or a social barrier. (emphasis added)

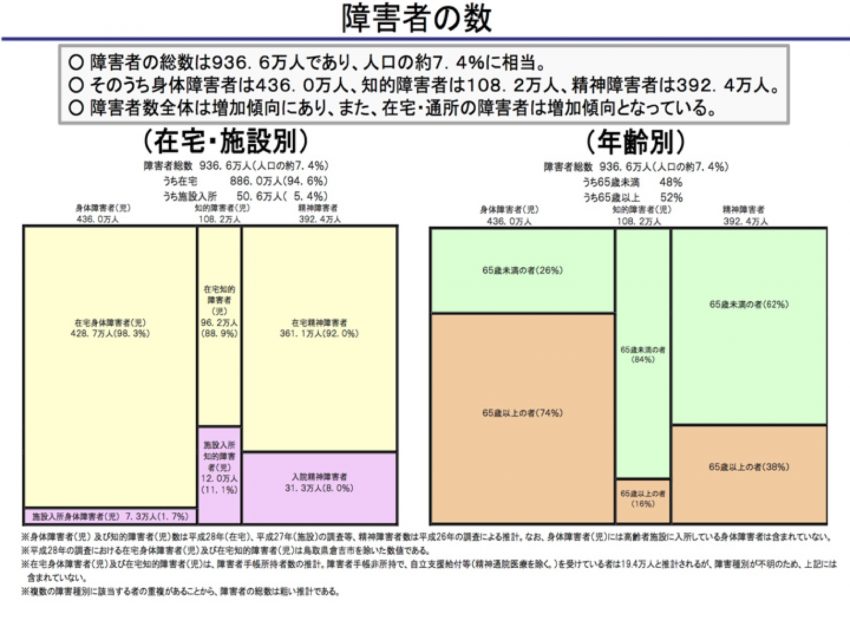

The important thing here, then, is that at current, when the concept of disability is interpreted according to a broader social model beyond the traditional medical model, people with disabilities cannot be identified immediately as people who carry a disability certificate (ie, people who are subject to welfare measures for children or adults with disabilities). In fact, when the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare conducted their Survey on the Difficulties People with Disabilities Face in Daily Life (Nationwide Survey of Children and People with Disabilities who Live at Home) in order to grasp the concept of disabilities on a wider scale, they included in addition to physical disabilities, intellectual disabilities and mental disabilities, so-called intractable diseases, dementia, and drug or alcohol dependence. Details are available on the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s website, but as a result of this survey and other work the government has announced that as of 2016 there were a total (estimated figure) of 9,363,000 people with disabilities in Japan (around 7.4% of the population) (see chart below).

Number of people with disabilities in Japan ( Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2018)

In other words, if we take it literally, while it depends on how we interpret the words “a state of facing substantial limitations in their continuous daily life or social life because of a disability or a social barrier” in Paragraph 1 of Article 2 of the Basic Law on People with Disabilities, if the definition of “person with a disability” in the Law Relating to the Promotion of Cultural and Artistic Activities for People with Disabilities follows the example of the Basic Law on People with Disabilities, the number of people eligible for support is potentially more than 9,363,000. This represents a sector large enough that it could be called national in scale, and in terms of the future is a number that contains within it the potential to trigger a fundamental rethink of the term “people with disabilities” as opposed to able-bodied people.

Conversely, however, this result also seems to be evidence that as long as people lead social lives, they will always experience some kind of disability (difficulty faced in daily life) depending on their individual situation. If so, the distance between art as a kind of creativity bestowed on everybody and disability narrows immediately. This is because all art almost always has a relationship of some kind with a difficulty faced in daily life in existing society. It was in this sense that I wrote above that art, unlike bijutsu, has a deep connection with welfare concepts as opposed to education with its determination of relative merits. In other words, rather than welfare learning from art the standards of value and assessment, art should learn from welfare the equality of opportunity of support for the purposes of expression. And in the future when we have a greater understanding of this, perhaps art will finally establish paradoxically by way of “disability” an essential connection to Article 25 of the Constitution of Japan, which stipulates that “All people shall have the right to maintain the minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living.”

1. “Meguru a–to wo meguru” was held at Kyoto-ba from February 1 to 11, 2019, and the exhibition-related 3rd Seminar for Considering the “Mediation” of Art by People with Disabilities: Considering Assessment, on February 7.

2. The Creative Support Let’s project “Expression or Less” stresses the importance of “expression” as a means of manifesting the self in everyone and recognizes each person’s existence through art-like techniques. On February 1 through 3, the Expression or Less Cultural Festival was also held at the Takeshi Cultural Center Renjakucho where the project is based.