Bridges and ladders: The forgotten Kanogawa Typhoon

Floating debris collecting at the Chitose Bridge, photographed by Shunji Ishii in 1958. Collection Kanogawa Resource Center; courtesy Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Numazu Office of River and National Highway.

Floating debris collecting at the Chitose Bridge, photographed by Shunji Ishii in 1958. Collection Kanogawa Resource Center; courtesy Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Numazu Office of River and National Highway.

The Cliff Edge Project is an art project founded in 2013 in the wake of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami that seeks to give visual expression in a hitherto unseen form to the relationship between natural disasters and art from multiple angles encompassing history, folk culture, geology and earth science without necessarily adhering to conventional contemporary art methods. Focusing on disasters that have occurred in the Izu region, the organizers have worked continuously on “updating” the collective memory of these disasters and how they are perceived by interposing art. With artist Kohei Sumi playing a central role, in 2015 the project unveiled “Hanto no Kizuato” (Scars on the Peninsula), its first substantial offering concerning the 1930 North Izu earthquake, at locations around the Tanna Basin on the Izu Peninsula (xn) where traces of the surface rupture caused by the quake can still be seen. Here, I would like to introduce the project’s second large-scale offering, “Mizu no Kataribe” (The Water Storyteller), an exhibition on the topic of Typhoon Ida (known in Japan as the Kanogawa Typhoon) that struck the region exactly 60 years ago. (1) On September 26 and 27, 1958, the typhoon triggered large-scale flash floods and debris flows, mainly in the mountainous area around the upper reaches of the Kano River, which rises from Mount Amagi in central Izu, and caused heavy damage across the entire catchment area. Among the hardest hit areas were the towns of Shuzenji (now Izu City) and Ohito (now Izunokuni City), where 853 people were killed or left missing (2) and where “scars” that will not easily disappear still affect the people and the land.

However, even if one visits the sites themselves, it is difficult to find any physical reference to these scars. In fact, it would be fair to say that compared to Typhoon Vera (known in Japan as the Isewan Typhoon), which struck the Japanese archipelago the following year, 1959, virtually nothing is known about the Kanogawa Typhoon. One of the distinguishing features of the Cliff Edge Project is that by limiting its scope to the Izu region, it focuses our attention not on the likes of the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923, the Kobe earthquake of 1995, and the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami of 2011 that everyone immediately remembers, but on the fact that disasters that in a sense have been forgotten because they have been obscured by the shadow of these events have in fact occurred all over the Japanese archipelago. In other words, the Cliff Edge Project deals with disasters that are not exactly the kind of “history” that appears in textbooks, but are too significant for the region concerned to be fully dealt with within the framework of “local research.” One could probably say that one of the goals of the project is to use the techniques of art to penetrate this vague territory that exists between history and local research and exhibit (ie, expose) and visualize it as a blank in history, thereby enabling as many people as possible to become involved.

Exterior view of the Kanogawa Resource Center.

Exterior view of the Kanogawa Resource Center.All photos courtesy the Cliff Edge Project (unless otherwise noted).

The venue for this latest exhibition, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport-administered Kanogawa Resource Center, is the kind of facility that, with the exception of inspections from outside, is not normally open to visits even by local residents. In fact, the fact that such a center even exists is probably virtually unknown even among the locals. Given the region suffered the kind of heavy damage mentioned above, why is this so? It may be due to problems involving operating costs or the absence of a designated manager. But it may also be due to the fact that the “materials” have been stored and administered as the property of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, creating a distance between the center and the people of the region. Another possible reason is that the damage caused by the Kanogawa Typhoon was so distressful that the people who know what it was like don’t want to remember or talk about it. On the other hand, whether due to confidence in the Kano River Diversion Channel that was later built or because the region has come to symbolize not disaster but disaster prevention, one also hears that the Kanogawa Typhoon is often brought up in discussions around the region on the subject of “disaster prevention.” There are few opportunities, however, for the widespread transmission from generation to generation of “memories and records” of the disaster.

Because disasters like the Great Kanto earthquake and the Isewan Typhoon are so deeply and indelibly ingrained in history, when it comes to discussing and rethinking them, society prevents those directly involved from maintaining their silence, regardless of how strenuously they try. Thus a fundamental gap arises between natural disasters that are large in historical terms and natural disasters that are (dare I say it) minor, a gap that cannot simply be reduced to an issue of scale. The former stick out historically (overshadowing the latter) and are more written about the more time passes, while for the latter it is the complete opposite in that they slip further from our memory and eventually become as good as nonexistent. The question the Cliff Edge Project raises is also an appeal regarding the real significance of this gap when it comes to disasters that produce a great number of victims (though for those directly involved, the difference between one death and tens of thousands of deaths is only a numerical one).

Let’s take a closer look. Though I said above that the exhibition venue, the Kanogawa Resource Center, was state run, it would be difficult even out of politeness to say it is stately. To be frank, calling it a hut rather than a center would be closer to the truth. For this exhibition, Sumi drastically reworked the interior, changing the facilities so that it functioned not so much as a “resource center” for handling records but as an “exhibition site” that appealed to the memories of visitors. The implication here is that while the exterior (institution) of this public facility was left the same, the interior (expression) was changed. In essence, the place itself as a venue was transformed into a border where public records and private memories abut. In this border region, Sumi arranged five main elements: a collection of objects (bricks) that actually survived the disaster; a series of “documents” chosen from the vast collection of photographs relating to the Kanogawa Typhoon in the care of the state; a physical model and 3D data on an enigmatic object associated with the typhoon; a collection of ladders of various sizes, the significance of which would be impossible to surmise had there not been an explanation; and a video work titled Mizu no Kataribe (The Water Storyteller) that was screened repeatedly in a separate room.

Bricks from the pier of the washed-away Ohito Bridge.

Bricks from the pier of the washed-away Ohito Bridge.

Installation views of the “Mizu no Kataribe” (Water Storyteller) exhibition.

Installation views of the “Mizu no Kataribe” (Water Storyteller) exhibition.

These five elements were not displayed in the above order, but rather, the given order reflects the degree to which these items are distanced from the Kanogawa Typhoon, an event that actually occurred in the past. Because while the video work in which local resident Keiji Matsumoto assumes the role of “storyteller” touches most tangibly on the Kanogawa Typhoon, at the same time, as the recollection (compilation of memories) of someone directly involved, its materiality dramatically differs from the previous four. As well, though I just described Matsumoto as “someone directly involved,” in fact the very reality of this is seriously undermined. For people like myself who are learning about the Kanogawa Typhoon for the first time, Matsumoto, who was on the spot and witnessed the devastation when he was eight years old, is unmistakably someone directly involved. However, in Matsumoto’s own mind this is not necessarily the case. His testimony includes the following:

Regarding the Kanogawa Typhoon, I’ve heard countless times about its wretchedness. As someone who remained completely dry, I was unable to join in such discussions in an empathetic way. As well, many of the people who had bitter experiences no longer want to speak about them. With the 60th anniversary approaching, I’ve come to wonder if there might be a way to tell people about the typhoon that involved more than just talking about its wretchedness.

Still from the video work Mizu no Kataribe (The Water Storyteller) featuring Kanogawa Typhoon survivor Keiji Matsumoto.

Still from the video work Mizu no Kataribe (The Water Storyteller) featuring Kanogawa Typhoon survivor Keiji Matsumoto.

Matsumoto happened to escape the disaster because his house was on a hill, in which sense he was “an outsider among those directly involved.” But such things can occur during even the most wretched war or disaster. That the “storytellers” who inform people today of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are able to “tell” their stories is because they did not die in those bombings. Those who had the bitterest experiences perished in the heat rays. This is the kind of contradictory state of affairs referred to by husband and wife artists Toshi and Iri Maruki, best known for The Hiroshima Panels, when they “told” us in their picture book Pika Don, “Not a single person can tell us what happened at ground zero.” In a sense, Matsumoto, too, is such a “storyteller.”

One could also say that Matsumoto was motivated to “tell” his story because he easily survived. Among others who survived the typhoon there are those who did not know how to “tell” their stories in words to people who were put in far worse situations than themselves and had no option but to keep their mouths shut. As well, as mentioned above, Matsumoto was eight years old at the time. Because of this his memory is not certain and in this sense, too, he is at a distance from being directly involved. He experienced it but cannot remember it clearly – one could also say that this is what sustains Matsumoto’s interest in the Kanogawa Typhoon to such an extent that it is almost uniquely conspicuous among those around him. In this sense, too, of the five elements of the exhibition, it is the documentary nature of the video work Mizu no Kataribe, which touches most concretely on the Kanogawa Typhoon, that needs to be relativized first of all.

The Kumasaka Elementary School cenotaph “Yuai no zou” (Statue of friendship), with Mount Jo faintly visible in the background. Photo: Noi Sawaragi.

The Kumasaka Elementary School cenotaph “Yuai no zou” (Statue of friendship), with Mount Jo faintly visible in the background. Photo: Noi Sawaragi.

The relativization of such categories as someone directly involved/outsider, record/memory and material/image (video) is an important outcome of this project. But beyond such a schema, in terms of either material or imagery, the most mysterious thing about it is the sculpted object that was displayed at this exhibition in the form of a model and 3D data. I am referring to the “cenotaph” concerning Kumasaka Elementary School, which is located in the affected area. Seventy-eight students who were attending the school at the time and two teachers fell victim to the Kanogawa Typhoon. The official name of this cenotaph, which stands beside the main entrance to Kumasaka Elementary School, is “Yuai no zou” (Statue of friendship). Painted white, its organic form is quite unlike most cenotaphs, in which the names of the victims and the details of the events are usually engraved in stone. Regarding this, Matsumoto, himself an elementary school student at the time, says he vaguely remembers a small statue (a model?) with a similar form sitting on the school principal’s desk.

Be that as it may, why a “statue of friendship” and not a cenotaph? First and foremost, who was the maker? There is talk that the public was invited to submit proposals, but Matsumoto says he has no memory of this. For a time there was also a theory that a statue that originally had no connection with the typhoon was repurposed (updated?) over time as a memorial statue, but when I visited the site and wiped away the moss and dirt that had adhered to the pedestal I found the inscription “1960 Statue dedicated to the teachers and students who fell victim to the Kanogawa Typhoon,” so there is no doubt that it is a memorial statue (plus it is said that there are wooden tablets inside this statue bearing the names of the teachers and students who died in the typhoon). It was also thought that the form was modeled on 342-meter-high Mount Jo, the symbol of the region. In fact, if one stands in front of the statue, this mountain rises like a gigantic rock behind it, and at the time of the disaster it was clearly visible in the distance as far as the eye could see, so the connection between the two was probably obvious. In a sense, there are similarities in the relationship between the undeniable, physically certain actuality of this statue and the uncertainty surrounding the reason for its existence on the one hand, and the “storytelling” of Matsumoto, the “outsider among those directly involved,” on the other. It could be that the strong interest shown by Matsumoto in this statue in the video work Mizu no Kataribe derives from the same kind of indistinctness surrounding it – not remembering something clearly despite having actually experienced it versus the reason behind something not being known despite it existing.

“Ohito Bridge, September 28, 1958,” photographed by Eiji Hashimoto in 1958. Collection Kanogawa Resource Center; courtesy Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Numazu Office of River and National Highway.

“Ohito Bridge, September 28, 1958,” photographed by Eiji Hashimoto in 1958. Collection Kanogawa Resource Center; courtesy Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Numazu Office of River and National Highway.

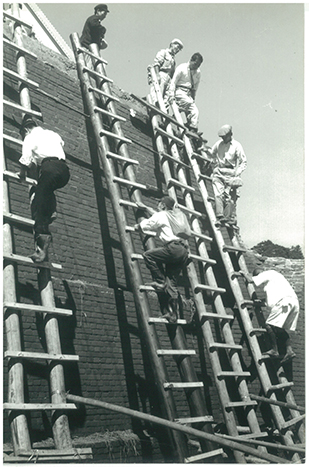

Something about this exhibition I must touch on quickly are the ladders. Why ladders? Well, when the Kumasaka end (to be precise, the access road) of the Ohito Bridge connecting Kumasaka and Ohito was washed away by a flash flood during the Kanogawa Typhoon, ladders were used so that people could climb up to the isolated bridge. The crucial thing here is the relationship between a “bridge” and a “ladder.” The two are similar in that points are used to connect two “ends,” a far end and a close end in the case of a bridge, the ground and a higher surface in the case of a ladder. However, there is also an important difference between the two. With a bridge, the grander it is the more solidly it is built, whereas with a ladder, the more moveable and portable it is the more useful it is deemed. The former is permanent, while the latter is temporary. However, the Chitose Bridge, which was well downstream from the Ohito Bridge, remained standing because it was far more solidly constructed, and for this reason it collected a large amount of floating debris, greatly increasing the number of victims caught up in the disaster (as explained by Matsumoto in the video, it was traditionally said regarding bridges in the area, where floods were common, that a bridge that easily collapsed was more reassuring in an emergency). That people placed ladders against such a “bridge” and crossed on their own initiative gives a hint as to the overall meaning of this project: “ladders,” representing memories that are private and therefore likely to fade and change and continually require updating, are placed against “bridges,” representing public records that are solid and therefore likely to become firmly closed or isolated.

Speaking of typhoons, 2018 saw one large typhoon after another strike the Japanese archipelago. There were several other large-scale disasters, too, including the earthquake in Osaka, floods in the west of the country, the closure of Kansai International Airport due to flooding, and the blackout affecting the whole of Hokkaido due to the Hokkaido Eastern Iburi earthquake (7 on the shindo scale). [With Emperor Akihito’s planned abdication this year marking the end of the Heisei era,] as of now, we have no way of knowing what the name of the next era will be, but looking at the example of the Edo period, the situation is similar to when the era name was changed due to a rash of disasters. I wonder what kind of era the next emperor will reign over. In any case, we are trying to build a bridge to a new era. Though perhaps what we need now is not a solid bridge but a ladder that can be adapted to the circumstances.

Special thanks to Mr. Keiji Matsumoto for providing me details of the damages from the Kanogawa Typhoon and the reading of the inscription on the Kumasaka Elementary School cenotaph.

The Cliff Edge Project “Mizu no Kataribe (The Water Storyteller)” exhibition was held from November 12 to 23, 2018, at the Kanogawa Resource Center (Izunokuni City, Shizuoka Prefecture).

1. Before these, the Project also staged an exhibition titled “Memories of Tanna” in 2014, comprising works Sumi produced on the subject of the Tanna Basin of the Izu Peninsula and related materials concerning the area.

2. Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Basic policy on river improvement, Kano River water system, “Outline of the Kano River basin and river,” p. 27.