The Rise and Fall of Taro Okamoto’s Tree of Life

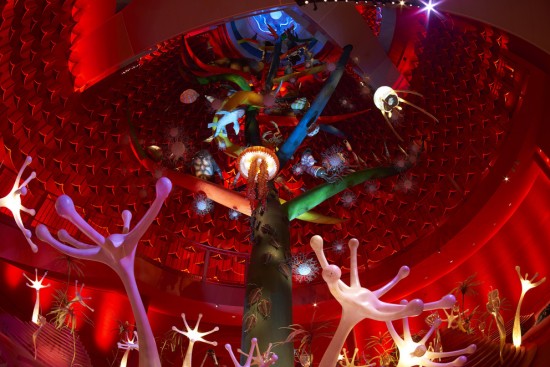

Taro Okamoto’s Tree of Life following restoration. All images of the Tower of the Sun: courtesy Taro Okamoto Memorial Foundation for the Promotion of Contemporary Art; photographed in cooperation with the Expo ’70 Commemorative Park Office.

The interior of Taro Okamoto’s Tower of the Sun was reopened to the public on March 19 this year. Fortunately I was able to complete my own inspection together with other persons concerned on April 7. Such has been the level of interest that reservations are already fully booked until August, with organizers hastily extending the evening hours in an effort to cope with the demand. The main reason behind the flood of bookings is probably the decision to adopt the system that has become noticeable at art museums in recent years, whereby visitors are required to book in advance, the number of people entering at one time is limited, and visitors are made to view exhibitions in groups, as opposed to not turning people away and having those that want to stay form endless lines. Upon actually seeing inside the tower, I realized the wisdom of this decision.

As should be clear by now, for this edition of Notes on Art and Current Events I have decided to write about the Tree of Life inside the Tower of the Sun, which was recently reopened to the public for the first time in decades. I have previously touched on this subject in number 70 of this series. In addition, a presentation I made titled Kuchu no uro, chitei no kao (A cave in midair, a face underground) has been reprinted in Art Anthropology 13, recently published by the Institute of Art Anthropology, of which I am a member, while a piece of art criticism I wrote titled Osaka banpaku no kakushin (The heart of Expo ’70) was published in the Culture section of the evening edition of Tokyo Shimbun on April 6. As well, there is a brief overview of the Tower of the Sun in the new booklet that is handed out to visitors when they enter the tower. Most importantly, the spatial media producer and director of the Taro Okamoto Memorial Museum, Akiomi Hirano, who was the main driving force behind the reopening of the tower, has not only been appearing in the media with an energy reminiscent of Taro’s adopted daughter Toshiko Okamoto, but he also has produced multiple publications representing various viewpoints, so I encourage everyone to refer to these. Given all this, here I would like to pursue this subject from a slightly different angle.

Taro Okamoto – Tree of Life

One of the reasons I was convinced of the wisdom of restricting entry to the tower was the fact that its main drawing card, the Tree of Life, is a massive structure, 41 meters in height. I can think of hardly any other examples where viewers must view an exhibit with such a difference in height between bottom and top while actually climbing it. The truth is we take it for granted that exhibits generally extend over a single level. Of course, it is not unusual for exhibits to incorporate height differences as a result of being installed on the first and second floors of a building, for example, and sometimes secondary exhibits will even be installed on stairs or landings visitors pass as they move between these floors. And while large-scale exhibits will often be positioned in atriums that span multiple floors, in these cases attention is always given to ensuring a stable footing for viewers around the exhibit. However, the Tree of Life is an exhibit in which the very experience of a difference in height is an integral part of the viewing process.

Originally, at the time of the Osaka Expo in 1970, escalators were installed in the vicinity of the Tree of Life. After passing through the underground space and arriving at the base of the Tower of the Sun, visitors got on escalators and gradually ascended the Tree of Life. However, because the exhibit was originally intended to last only as long as the expo itself, it was not envisaged that people would be entering on an ongoing basis, and while beyond all expectations the Tower of the Sun itself was left intact, the structure was far from something that could be kept open to the public in its existing state.

Taro Okamoto – Sun of the Underworld, the original of which went missing, and was reproduced based on photographs.

With this large-scale restoration of the tower’s interior, such conditions had to be met from the outset. Specifically, the escalators were removed and stairs installed in their place, but of course, in order to avoid the kind of steep gradients that would be hard on the knees, the stairs were configured with gentle gradients and generous landings provided here and there. Logically speaking, these landings would be the least burdensome spaces for viewing, but in fact they are in the worst locations in terms of observing the Tree of Life. So what went wrong? In the sense that the passageways are sloping and people view the works while ascending the corridors under their own steam, the Tree of Life calls to mind such examples as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. However, even in such peculiar designs as the Guggenheim, the walls are configured for level display irrespective of the slope of the floors. Perhaps the closest examples to the Tower of the Sun and the Tree of Life are actually the sazaedo, or “turban-shell halls,” of the Edo period that had corridors with helical structures. As is the case with the Tree of Life, people entering and leaving these turban-shell halls follow different routes and, as mentioned below, are unable to “go back.” This reminds me of how visiting the Tower of the Sun has often been compared to “visiting a womb.” In the wake of my own visit, however, I would go a step further and describe it as like “visiting a turban-shell-hall-like womb.”

The sazaedo in Aizu-Wakamatsu (the former Entsu Sansodo of Shosoji temple) in Aizu-Wakamatsu, Fukushima. Photo (above) Kounosu, (below) Takuya Oikawa.

Unlike places like the Guggenheim, the objects on display as part of the Tree of Life are anything but planar. In fact, because the exhibit traces the evolution of life by way of a tree-like structure, items (models of creatures) that at one point appear before our eyes later appear as layers of more primitive items on lower levels. Accordingly, to make sense of it all, viewers must continually take in the entirety of the tree structure while confirming their current location by looking above their heads and below their feet. As mentioned above, because the landings that ought to provide the most stable viewing conditions are located in blind spots far from the tree structure, in order to replicate the original viewing experience, visitors must proceed along the outer edge of the stairways as they move higher and higher by climbing one step at a time. What I am trying to say is that essentially this is a rather dangerous arrangement.

Looking at some of the rare documentary footage of the Tree of Life shot during Expo ’70, it is clear that the expressions on the faces of visitors with children harden as they are carried to the upper levels on the escalators. This has been put down to the facts that the interior of the Tower of the Sun and the Tree of Life were painted in unrealistic primary colors and that the viewing experience was accompanied by the eerie climax of Toshiro Mayuzumi’s “Hymn of Life” – an explanation with which I actually agree. However, when I tried to imagine what it must have been like with the above in mind, I had to admit it was also possible that, because they were being carried higher and higher on escalators, which were still unusual at the time, with no way of going back, and because the lighting was reduced and the handrails were surprisingly low, they were simply feeling weak at the knees.

In order to avoid such dangers, the line of flow newly assigned to the stairs has been protected with tall, transparent, acrylic barriers, and while people’s field of vision has been maintained, the arrangement is such that visitors cannot lean out, for example, to get a better view. In other words, even though one was unsteady on one’s feet to begin with, the structure is such that one would want to lean out to get a better view. It is for the same reason that photography is not permitted inside the reopened tower. According to Hirano, if photography was permitted inside the 41-meter-tall tower, it would be impossible to stop people using smart phones to take photos, which they could do without leaning out by extending their arms. If someone’s hand slipped and they dropped their phone, even a small falling object could became a lethal weapon on the floor below, which is an open area with no boundaries, and a fatal accident could easily result.

Taro Okamoto – Tree of Life

I had viewed the Tree of Life three times before – twice when it was practically in ruins and once when construction work was being done inside for its current reopening – but because I never entered it during Expo ’70, this was the first time ever that I saw it “open to the general public.” As an elementary school student, going to Expo ’70 and in particular going inside the Tower of the Sun was a “dream” I was unable to fulfill, so for this reason alone, being able to enter not for investigative purposes but as just another visitor was a marvelous experience in which I seemed to lose all sense of time, and it was a deeply moving occasion. But precisely because of this I was constantly trying to take in with a single glance the distance from right down at the base where unicellular organisms were assembled to my current position in an effort to view the entirety of the Tree of Life, even if it meant pressing my body against the acrylic barrier, and so the overwhelming impression I got was “It’s really tall,” which was different from my “dream.”

I am not sure whether such an exhibition format, which could be described as fraught with danger, is something that Taro Okamoto had in mind from the beginning. However, based on Taro’s statements and the memos he left behind, at the least I can say that at the time of Expo ’70, it was not solely a functional consideration aimed at encouraging visitors, whose numbers were no doubt vast even as an hourly figure, not to gather in one place but to keep moving forward (ie, up) along the established traffic lines. According to these sources, Taro gave the following “spatial conditions” with regard to his “basic approach to artistic methods inside the tower”:

It should be a cylindrical space with no partitions extending in a vertical direction.

It should function simultaneously as exhibition space and as a corridor linking the upper and lower exhibitions spaces.

The traffic lines should be prescribed as one way.

This direction should be from bottom to top.

Visitors should be transported mechanically on escalators.

Viewing points and fields of vision should be able to be foreseen in advance.

The time required to pass through the tower should be determined in advance.

This time should be approximately five minutes.

(From a memo from the time displayed at the exhibition “Tower of the Sun 1967-2018: What Did Taro Okamoto Question?” Part 1, October 13, 2017 – February 18, 2018, Taro Okamoto Memorial Museum. Underlining added.)

What Taro Okamoto is saying here repeatedly in different ways is “there should be no going back.” Moving through “space with no partitions extending in a vertical direction” “from bottom to top” while “foreseeing in advance” layers representing the totality of the evolution and mystery of life, or in other words seeing this in its entirety with one’s own eyes, and yet doing so with one’s body leaning over, one’s movement “prescribed as one way” and one’s time “determined in advance” is an approach befitting Taro Okamoto, who liked to continue moving forward one step at a time regardless of the consequences.

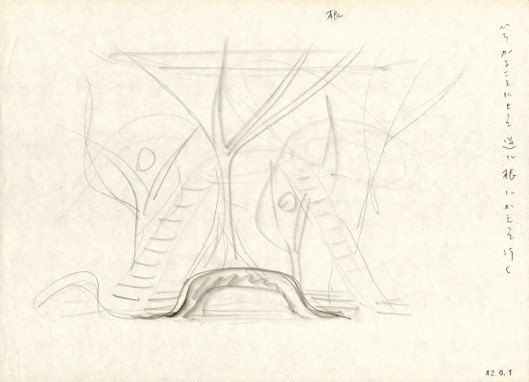

Furthermore, an early sketch Taro began working on prior to the announcement of his appointment as producer of the Theme Pavilion at Expo ’70 contains memos in Toshiko Okamoto’s handwriting reading “roots” and “by spreading out, [it] conversely goes back to its roots.” These were probably written by Toshiko in an effort to record immediately something Taro said at the time. This was before the Tower of the Sun as we know it appeared. In other words, it is very likely that these mentions of “roots” and “by spreading out, [it] conversely goes back to its roots” were the first inspiration before everything else, and it may have been from these words that the Tower of the Sun and even the Tree of Life were eventually born.

Taro Okamoto’s image sketch for the Tower of the Sun exhibit – 1967. Photo courtesy Taro Okamoto Memorial Foundation for the Promotion of Contemporary Art.

But what does “by spreading out, [it] conversely goes back to its roots” actually mean? Given that there is no way of asking Taro directly, we can only guess. But looking at the “spatial conditions” of the <i>Tree of Life</i> that eventually appeared, it is possible to reinterpret the Tree of Life as something that “by spreading out, conversely goes back to its roots.” If the Tree of Life deals with the evolution of life, then evolution actually gives rise to the diversity of species, in which sense, regardless of how great the number of species becomes, their origin is a single cell (unicellular organism), which is in accord with Taro’s claim that “evolution is not an advance; rather, we should return to the freedom of amoebas.” Taro thought that humans, who are regarded as occupying the top of the evolutionary tree, “must return to their roots,” and even if he casually added to the Tree of Life “the risk of death” and “forward motion with no possibility of going back,” it would not be strange at all.