Three years to collect seawater, ten years to scatter it – On the Oku-Noto Triennale/Movement

SuzuPro at Kanazawa College of Art – The Oku-Noto Mandala (2017), former Yagi residence, Suzu, Ishikawa.

SuzuPro at Kanazawa College of Art – The Oku-Noto Mandala (2017), former Yagi residence, Suzu, Ishikawa.All photos (unless otherwise noted): Kichiro Okamura, courtesy Oku-Noto Triennale.

Upon entering the old Meiji-era house that stands unobtrusively in the central Iida district, one’s entire field of vision is filled with Oku-Noto (ie, the world). The mandala depicting cultural exchanges between Suzu and mainland China, and animal and plant ecosystems painted on the walls inside the building by a team of university teachers and students expresses the unexpected dynamism of the land and sea around Oku-Noto. The work was installed in conjunction with the 1st Oku-Noto Triennale in 2017.

Hours into the New Year, at 4:10 PM on January 1, 2024, a powerful earthquake centered on the outer, “Oku-Noto” area on the Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa prefecture struck without warning, registering a magnitude of 7.6 on the Richter scale. The Meteorological Agency immediately issued a tsunami warning and television stations desperately appealed for viewers to evacuate right away. What immediately came to my mind was Suzu city. I had participated in the second edition of the Oku-Noto Triennale, an event that began in 2017 and was held in 2021 under the official title “Suzu 2020+ Oku-Noto Triennale” (yes, this festival is called none other than “Suzu”) after being postponed for a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It was an extremely enriching experience, and even now, with my memories of the works serving as triggers, I can vividly recall the routes and streets I wandered down, the views out over the sea, the people I had exchanges with, the ryokan where I spent a peaceful night, and the many substantial meals I enjoyed. I still cannot believe that many of them have been damaged or lost.

To date, whenever a major disaster has struck Japan, I have examined it critically from the standpoint of art. This work culminated in the publication of Seismic Art Theory (Bijutsu Shuppan) in 2017, but as noted repeatedly in the book, it was also none other than a “pre”[quake] work, as in Japan there is no “post” in a pure sense when it comes to earthquakes, with one shake always occurring in advance of another that will strike eventually. However, the Oku-Noto earthquake is no longer “pre.” Which means I must write something about it. But to be honest, I cannot write anything yet. For that reason, I have decided to reprint here the introduction I contributed to the official “Suzu” catalog in advance of this disaster, which it must be said is still unfolding, in which I wrote about my own personal feelings and thoughts concerning Suzu. If there is anything I can do at this time, then this is it.

Noi Sawaragi

February 5, 2024

*The following text is an English translation of my essay “Three years to collect seawater, ten years to scatter it—On the Oku-Noto Triennale/Movement,” which was originally published [in Japanese] in the Suzu 2020+ Oku-Noto Triennale catalog. I would like to express my gratitude to the triennale director, Fram Kitagawa, who consented to its reproduction here, and to everyone else who cooperated.

The number of art insiders who first learned of the name “Suzu” through the Oku-Noto Triennale is probably quite large. It is customary when beginning with a preface like this to add that it also applies to oneself, but in my case it is different. In fact, I learned of the name “Suzu” at one of my regular izakaya.

I have always been interested in eating and drinking, and from a young age tried out various eating places. However, as I grew older, the number of establishments I frequent decreased, and from a few years ago I can count the number on the fingers of one hand. The number reduced naturally over time in accordance with my own preferences, but no matter how one looks at it, the grilled fish served at one of these places really stands out.

At this kind of level, care in the selection of ingredients and discernment when it comes to seasonality are to be expected, so there is hardly any major difference when it comes to these. Once, I asked the owner/chef about this in a casual manner. “Hmm, I wonder if it’s because we use salt from Suzu?” was his answer. “I tried all sorts of salt, but ultimately that’s where I ended up, and I’ve used nothing but Suzu salt ever since.” “Suzu?” I said. The word was completely unfamiliar to me. But that was my first encounter with the city called Suzu.

Perhaps because of this, even after it was decided I would be visiting Suzu for the first time in conjunction with the Suzu 2020+ Oku-Noto Triennale, Suzu salt was constantly in my mind. Every time I went to that Tokyo izakaya, as I sat at the counter and yielded to the pleasant effects of the alcohol, I thought to myself, “I wonder what kind of place Suzu is. How are they able to make salt that brings out such wonderful flavors? Is there some secret? If I get the chance, I’d like to look into it,” so despite the fact that I had never been there, in fact I was experienced in my own way when it came to Suzu.

Motoi Yamamoto – Cloister to Memories (2021), former Kodomari nursery school, Suzu, Ishikawa.

Motoi Yamamoto – Cloister to Memories (2021), former Kodomari nursery school, Suzu, Ishikawa.Upon entering the single-story former nursery school that stands on a promontory in the Misaki area, one is confronted by a continuous “tunnel of drawings” rendered in white on the blue-painted corridors, walls and ceilings. Filling the playroom beyond this is a “salt garden,” in the middle of which stands a set of stairs made of salt. As is mentioned elsewhere in this essay, salt has special significance in terms of the birth and sustenance of humankind. At the same time, salt is also a medium used for purification, cleansing, and maintaining ties with things that have been lost. One could say that Suzu salt is a symbol of these things.

For that reason, even after I actually arrived in Suzu, which viewed from Tokyo is “the back of beyond,” and looked around at the “cutting-edge” art, I could not help feeling that it was always somehow connected to that Suzu salt. Tokyo and the back of beyond seem the exact opposite, but while they are located in the “cutting-edge” city of Tokyo, the big city izakaya that I like are probably all in multitenant buildings and consist solely of long, thin counters that stretch back from hard-to-find entrances. That’s right, they resemble peninsulas. Perhaps the izakaya with the boss who only uses Suzu salt was located in the cutting-edge city of Tokyo in a different sense and, if I may venture to say it, was a place not unlike Oku-Noto.

But there was another reason why I was attracted to that “Oku-Noto in the middle of Tokyo.” Unlike fine restaurants where fine dishes are produced like magic from somewhere behind a wall, at peninsula-like places where one can see with one’s own eyes the dishes being made from beginning to end on the other side of a single counter, seeing this process with one’s own eyes accounts for a great deal of the enjoyment of the meal. It is often said that we taste with our eyes, but if that is true then surely watching the process of food being prepared ought to be just as appealing.

Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro – Gomen ne Sunao ja nakute / Sorry, I’m not straightforward (2021), former café/bar An An, Suzu, Ishikawa.

Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro – Gomen ne Sunao ja nakute / Sorry, I’m not straightforward (2021), former café/bar An An, Suzu, Ishikawa.In the coastal Shoin area is Kissa An An, which was once popular as a café during the day and as a snack bar where people could enjoy karaoke and live music at night. Inspired by the fact that fishermen traditionally used the waxing and waning of the moon to gauge high and low tides, the giant model of the moon suddenly pulls viewers into another, celestial dimension. The title comes from the theme song to the anime Sailor Moon.

It seems like I am going on and on about things unrelated to art, but it is about time I offered an explanation. Because what I want to say is that of all the things going on at the events we call arts festivals, I think being able to see this process of making things is in fact one of the biggest attractions.

Due to the nature of my work, I often visit exhibition venues at the preparation stage before they open. At a certain point, as someone who has witnessed firsthand how the making of things progresses through various divisions of labor, and trial and error, entering a venue where the curtain is going up with exclamations of self-encouragement after everything has been neatly put in order and all the groundwork laid left me feeling somehow unsatisfied. Though I know it is impossible, I always think about the many discoveries that could be made if that process could be shared with everyone. And so whether it be an exhibition or an arts festival, I always look forward to an open counter rather than an isolated kitchen.

However, the things that live up to these expectations are different from so-called “open studios” or complex installations that continue to transform moment by moment over the course of an exhibition. Looking at it a different way, even at regional arts festivals that ought to be close to open counters to begin with, processes and exhibits have been separated and consequently the focus has tended to be on the finished “dishes” alone.

In this respect, the first arts festival I attended in Suzu certainly had the feeling of a peninsula-like open counter. Perhaps this was because it was postponed due to COVID, and even when it was finally staged after a year, trial and error was required, and there were parts where the processes were exposed. However, in no way did I sense this was a negative element. Rather, like the demanding process of salt making, so much so in fact that that process came to mind, it seemed that the connections between the land and the works stood out as if they were inseparable.

Hiraki Sawa – Illusions (2021), former Hiki community center, Suzu, Ishikawa.

Hiraki Sawa – Illusions (2021), former Hiki community center, Suzu, Ishikawa.Located in the Hiki area at the northernmost tip of Suzu, this work is housed in a facility that was originally used as a community center. A “house” used by local residents as a place to gather and participate in various activities was brought back to life by the artist as an “art community center.” Houses based on blood relationships and houses where communities come together are both essentially institutional things and nothing but a kind of “illusion.” Art as a shrine for the community makes this illusion apparent.

David Spriggs – First Wave (2021), former fishing gear warehouse, Suzu, Ishikawa.

David Spriggs – First Wave (2021), former fishing gear warehouse, Suzu, Ishikawa.Housed in an enormous warehouse (built to repair fishing nets) located just inland from the Takojima fishing harbor, this exhibit literally deals with a bright red tsunami. In this sense, in a disquieting way it became a portent of the tsunami generated by the 2024 Noto earthquake, but the wave is also a metaphor for the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and hints at the crisis-ridden age in which all of us now live.

In fact, salt making is apparently something that was finally achieved through a series of extremely rigorous tasks from ancient times. Things would have been even more difficult in a natural environment that is harsh even at the best of times. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that precisely because the natural environment is harsh, people’s livelihoods were naturally narrowed down to salt making. Because there is an inseparable relationship between this fact and the depth of flavor of Suzu salt.

According to Suzu no rekishi (The history of Suzu) (edited by the Suzu no Rekishi Editorial Committee, produced by the Hokkoku Shimbun, published by the Suzu Municipal Office, 2004), published to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Suzu becoming a municipality, “The drying of salt in fields was carried out all along the coast of Noto, but the fact that salt fields were particularly numerous in Suzu is probably due to the following six reasons,” (p. 245). The following six factors are then itemized.

1. The Kaga domain placed an emphasis on salt production in Suzu

2. Fuel was easy to obtain

3. There were many sandy beaches on the coast facing Toyama Bay, making it easy to create salt fields

4. The numerous pebbly beaches on the Sotoura coast made creating salt fields difficult, but the long sunshine hours in this area were an advantage

5. There were no major rivers, meaning the salt content of the seawater was high (A divergent view appears on p. 150 of Suzu-gun shi [The history of Suzu district])

6. Rice production was insufficient due to the lack of rice fields, but there was no other production to take the place of rice

All of these factors are also the flip side of the harshness of the natural environment in Suzu. But it looks that way because this was one-sidedly inferred based on the former system of centralized authoritarian rule that made rice cultivation the basis of value. The fact that fuel was easy to obtain was probably because the mountains go right down to the sea, another industry developed because rice could not be grown, and because of its nature as a regional specialty it came to be protected by the domain. In other words, a “cutting-edge” industry developed in Suzu precisely because it was “the back of beyond,” resulting in the emergence of a salt flavor beyond compare.

Is this not similar to the making of things at some arts festivals in Japan, where the remoteness of the location has actually been turned into an attraction? Returning to the subject of Oku-Noto, in Suzu, perhaps art is like salt. In which case the processes behind it should willingly be made public, shared and communicated in a form different from other arts festivals. In this sense, I think “Suzu’s Great Clearance” at Suzu Theater Museum: The Ark of Light,1 which impressed me the most among all the exhibits I encountered on this trip, is a perfect example.

Yoshitaka Nanjo – Sea of Argonauts (2021), Suzu Theater Museum: The Ark of Light, Suzu, Ishikawa. Photo Keizo Kioku.

Yoshitaka Nanjo – Sea of Argonauts (2021), Suzu Theater Museum: The Ark of Light, Suzu, Ishikawa. Photo Keizo Kioku.Suzu Theater Museum: The Ark of Light is situated on a hill in the Otani area, whose rugged topography is directly adjacent to the Sea of Japan. Located in the middle of the museum, this work involved the creation of an artificial sandy beach from earth and sand dug up from the area’s ancient strata. The artist created a miniature garden from the seashells, a wooden boat, a piano and a fishing net strewn across this beach, and with this site serving as an object to which spirits are drawn or summoned, songs and poems written in old books left behind by the deceased are brought back to life.

This is an archive in the form of a program in which one “keeps in touch with the work of an artist.” In which case the record is probably the same. The catalog in which this text will appear is also no doubt contained within this living vessel, described as “aiming not for a traditional, qualitative account, but for a dynamic account of how the artist engaged with the region, of where in the region light shone by way of the art and of how the site changed” (from the written request for this text).

When I thought about all these things together, I wondered if perhaps the arts festival in Suzu had already set off along a path different from that of “arts festivals.” One factor behind this is that in the message he wrote for the catalog for the 1st Oku-Noto Triennale in 2017, the mayor of Suzu, Masuhiro Izumiya, commented as follows:

I regard the Oku-Noto Triennale not simply as an event, but as a “movement.” I want as many people as possible to understand the joy of living in Suzu, where self-realization and contribution to the region form a complete whole. I think of the Oku-Noto Triennale as a movement that will stem the flow of people and change the current of the times from the back of beyond.

Is this not precisely an arts festival as a process? In this respect, too, the arts festival in Suzu is similar to salt making. In which case, perhaps the Oku-Noto Triennale is an alternative to the arts festivals that exist today in the form of the Oku-Noto Arts Movement.

However, the reality is not that simple. As suggested by the director of the Oku-Noto Triennale, Fram Kitagawa, when he noted in his message in the same catalog, “How the arts festival was created,” “In order for connections inside and outside the region to trigger a chemical reaction, it needs to continue for at least 10 years (three times)” (p. 11), though officially arts festivals run for limited periods, in reality this has little conclusive meaning. This is all the more true in the case of movements.

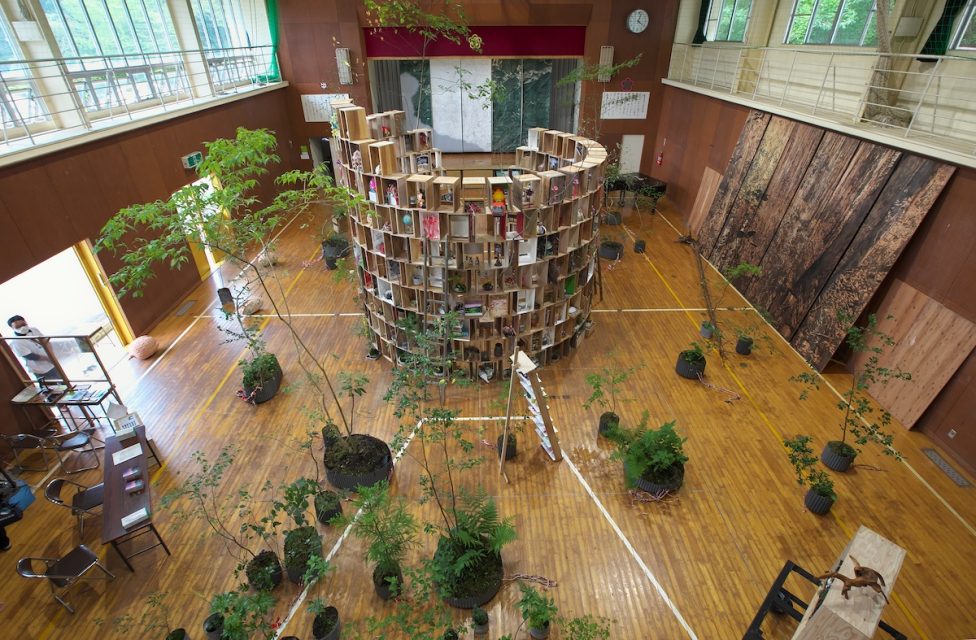

Team KAMIKURO installation (2021) at the former Kamikuromaru Primary and Junior High School, Suzu, Ishikawa; (center) Koji Nakase – Kamikuromaru, Zaen, Circulation, Mandala 1 (2021).

Team KAMIKURO installation (2021) at the former Kamikuromaru Primary and Junior High School, Suzu, Ishikawa; (center) Koji Nakase – Kamikuromaru, Zaen, Circulation, Mandala 1 (2021).The Wakayama area is located in the mountainous region inland from the sea where there are also terraced rice fields. Since 2012, the buildings of the former Kamikuromaru Primary and Junior High School that serve as the venue have been used by specialists in various fields carrying out research in the region as part of a partnership between the city of Suzu and Kanazawa College of Art, and projects applying this to the “art sphere” have been steadily pursued. In 2021, the results of these efforts over ten years were brought to fruition in a single space.

Incidentally, considering the connection between Suzu and salt making, it is very interesting that in the same message, Kitagawa gives the standard of “a minimum of ten years, or three times on a triennial basis.” I say this because in Suzu, regarding salt making, too, there is the expression, “Three years to collect seawater, ten years to scatter it,” a reference to the time it takes to master each task. I am unsure of whether Kitagawa knew this. But in any case, creating art at the back of beyond that is Suzu is directly related to salt making in the same region. By no means did the place where delicious salt is made and the land where profound art is made become connected by coincidence.

The commentary on salt making in the above-quoted Suzu no rekishi goes on to suggest a major connection between salt and people. “This region in which we live came into existence around 4.6 billion years ago. After a while, the oceans were formed and the chlorine and sodium in those oceans combined to create ‘salt.’ And it was from the oceans that the world’s first organisms appeared.” (p. 244) Salt is the origin of life all around the world, and this life came out of the sea and crawled onto land where it ultimately produced humankind. It is probably well known that the salt in our blood is said to be a remnant of this. Places were good salt is made are undoubtedly also places where good human life is nurtured and passed on. And it is in such a place that art peculiar to the Oku-Noto Triennale is now truly being made.

Postscript: The photographs, newly added for this republication of the text, are all of works that impressed the writer while visiting the Suzu 2020+ Oku-Noto Triennale.

Suzu 2020+ Oku-Noto Triennale was held from September 4 through November 5, 2021, at multiple locations throughout the city of Suzu, Ishikawa prefecture.

For details, see https://www.oku-noto.jp/ja/okurazarae.html

Note from ART iT: This marks the final issue of “Notes on Art and Current Events” in English translation. The original (Japanese) series will however continue to be published on the Japanese site.