II. Intermediate: Ablegen, Anlegen, Auflegen, Auslegen, Belegen, Beilegen, Darlegen, Einlegen, Erlegen

Ming Wong discusses Fassbinder, Pasolini and international attitudes toward cross-dressing.

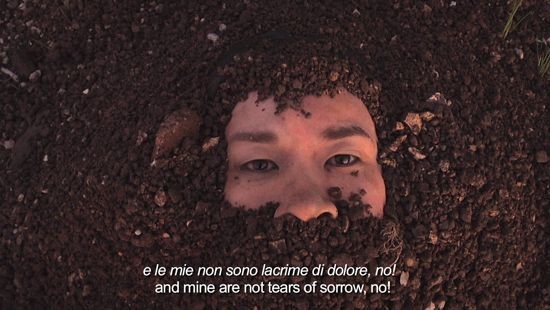

Video still from Devo partire. Domani / I must go. Tomorrow (2010).

Video still from Devo partire. Domani / I must go. Tomorrow (2010).ART iT: We were just talking about how your early work Whodunnit? uses language to expose the mechanisms of identity. Would you say this is a theme you have explored consistently throughout your career?

MW: Yes. In subsequent works I have reinterpreted foreign-language films – so-called World Cinema – using scenes from Fassbinder’s films or from Passolini’s Teorema (1968), and forced myself to learn to speak German and Italian. I’ve done Spanish as well. The process of learning an unfamiliar language and repeating it and the failures that are involved in that process are all part of the work. There’s this mimicry, this parroting or imitation, which is a basic activity of forming your own identity. Actually it’s not just in language but also applies to behavior, when people copy what they see on TV or in popular culture. This mimicry affects how we speak and how we carry ourselves. Language is just one particularly strong aspect of it.

ART iT: Given the idea of inserting yourself into multiple roles and the use or misuse of language, are there any artists who you see as reference points? For example, Yasumasa Morimura and Cindy Sherman come to mind from a visual reading of your work.

MW: Many people compare me to Morimura and Sherman. I can see the similarities, and in the case of Morimura I’m interested in the process of what he decides to work with and how his work deviates from the original. But personally I feel I am more influenced by artists who work with language, like Bruce Nauman.

ART iT: Do you necessarily prioritize language over the visual aspects of your work?

MW: Both aspects come together. When I say I admire artists who work with language, I am referring to artists who work with language in a visual way, in the performance of language as opposed to textual works. So I think Nauman’s videos dealing with language, meaning and repetition are fantastic – the talking heads or the clowns, those are very essentialized and powerful works. The performance of language is an interesting marker for me, so it extends beyond contemporary artists to something like dance, where movement, expression and language are used not as worded play but as material. I find Pina Bausch fantastic because with her dance you don’t need to understand the language.

Top: Video still from Angst Essen / Eat Fear (2008). Bottom: Video still from Life & Death in Venice / Leben und Tod in Venedig / Vita e Morte a Venezia (2010).

Top: Video still from Angst Essen / Eat Fear (2008). Bottom: Video still from Life & Death in Venice / Leben und Tod in Venedig / Vita e Morte a Venezia (2010).

ART iT: Would you say then that your continued use of the “language-study” format that you pioneered with Four Malay Stories is reflective of a conscientious conceptual approach?

MW: Well, it’s still personal. Four Malay Stories is very personal and the newest work is also very personal. Four Malay Stories represents a part of me that I had forgotten or lost. I grew up watching these movies on TV in the background. I didn’t understand them at the time but they’re something that was an important part of my cultural constitution. They made me conscious of the fact that I come from Singapore, which is surrounded by the Malayan archipelago, and that sets me off from mainland Chinese people or Chinese from other parts of the world. I have this connection with the origins of the nation of Singapore. That relationship is changing now that the government is seeking to strengthen its ties to mainland China and more and more new immigrants are coming to Singapore from there. The generation to which I belong, born in the 1970s, have witnessed all these changes. You can’t see the influence of Malaysian culture so clearly today. I wanted to bring it back out into the open. So the work represented a past, and my own past, and that of my parents.

The subsequent work based on Fassbinder’s Tears of Petra von Kant, Lerne Deutsch mit Petra Von Kant (2007), was also very personal. I think I was going through a crisis as an artist because I was in London, it was too expensive, things were changing but it was still difficult and I was about to move to Berlin. I had to confront what it meant, leaving all my security and familiar contexts behind. The original character is a washed-up 30-something-year-old designer, and I thought I might find myself in a similar situation in Berlin as a washed-up 30-something-year-old artist, so it was good to see how you would express yourself in German if you were in such a situation. It was a cathartic work to make.

Then Angst Essen / Eat Fear (2008), based on a Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974), was personal because when I arrived in Berlin I ended up in Kreuzberg where all my neighbors were Turkish and it was not typical Germany, it was Turkey. Some of the people in Kreuzberg are second- or third-generation immigrants but things haven’t improved for them. The German government has been really slow in dealing with this issue and I felt sympathetic to this situation, so to me the original film was the perfect analogy. Remaking that film was a wonderful testament to the idea that nothing has changed since 1974.

My latest work, Life and Death in Venice (2009-10), is also about the artist in crisis. I represented Singapore at the 2009 Venice Biennale, so what am I going to do next? I’m going to turn 40 soon and I’m thinking about age, thinking about mortality, and the original Death in Venice (1971), directed by Luchino Visconti, encapsulates that because it’s about age, death, youth, beauty, all of that. I think my choice of material always stems from the heart in some way.

ART iT: Fassbinder has a reputation as a boundary-pushing filmmaker working with issues of sexuality and identity, but in a way you can also compare him to P Ramlee in the sense that he’s a genre filmmaker who’s simply added unconventional twists to the stock characters of melodrama or crime stories.

MW: That’s true. And also seen collectively Fassbinder’s films are a critique of his fellow man, of German society. He’s one of the few filmmakers from the New German Cinema who was fearless enough to go straight to the heart of social insecurity in post-war Germany, when they were trying to make up for the war and start anew. The post-war recovery had such a big impact on the country’s national identity, but nobody dealt with it the way that Fassbinder did. That’s why I admire him, because he exposed German society for what it is.

ART iT: How about Passolini and Visconti? What attracted you to them?

MW: Passolini is another idol. Like Fassbinder, he’s an outsider and a critic of society. In a way he got on so many people’s nerves. He was such a vocal critic of Italy’s shift toward becoming a materialistic, superficial consumerist society and the resulting loss of heritage.

So Fassbinder and Pasolini were outsiders within their own contexts. Fassbinder was from Munich and everyone looked down on him as a fat German peasant, you know, “Who is this guy who makes these really loud, awful works?” Not all his films are good. He was the outsider. He hung out with the misfits of society. But unique, unconventional things came out of that.

Top: Video still from Life & Death in Venice / Leben und Tod in Venedig / Vita e Morte a Venezia (2010). Bottom: Video still from Angst Essen / Eat Fear (2008).

Top: Video still from Life & Death in Venice / Leben und Tod in Venedig / Vita e Morte a Venezia (2010). Bottom: Video still from Angst Essen / Eat Fear (2008). ART iT: But what does it really mean when you adapt works such as Petra von Kant? I can see how it relates to your personal situation, but what is your audience? Are you addressing a European audience who will see it and appreciate the sense of alienation that results from the immigration process, or is it for a Singaporean audience, for example?

MW: Well, it’s for anybody. I’m not making Angst Essen / Eat Fear for a particularly German audience. People who know the original material will take away an additional layer of understanding, but it doesn’t matter if you don’t know Fassbinder or anything about the original material. What you will see is one artist trying to be these different characters from a work that deals with xenophobia and class systems, and I think these are universal struggles.

But it’s all slightly ridiculous. Both the original material itself and what I do with it has to be slightly ridiculous, because it gives the viewer a sense of distance. So even if you’re familiar with the material you look at it with a new eye, and if you’re not familiar then you have a distance to begin with. It’s the past that you sort of know about, you may have heard about, you may not quite remember, and there are all these irritations, all these barriers to believing in what you are seeing in my works, because some of it is badly done, some of it is unrealistic, and that’s where the distance becomes important. I’m not making it for any particular cross-section of society; I think it should appeal to different people.

ART iT: What interests me about your work is the idea of cross-dressing, partly in the comedic sense that there is something funny about a man dressed as a woman, but also in a subtly politicized sense that it’s not just a gender issue, it’s about challenging the roles determined for us by society.

MW: Age, gender, class, nationality, everything. In fact, I’m trying to stretch that. What else can it be, if it’s not just gender? I’m very aware that I’m based in Berlin and the primary audience for my works are in Europe or America, although I am increasingly exhibiting in Asia as well, and I’m trying to see the different readings that result from these different contexts. There’s one reading that I’m an actor playing different roles and that I am Chinese, or Asian, which I understand might be unusual because there are not many male, Asian international film stars. It’s not something that mainstream European and American audiences are used to seeing.

ART iT: How do you feel people in Japan responded to Four Malay Stories when you showed it at the Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions in Tokyo earlier this year?

MW: I think Japanese audiences can identify with it. One thing that I love to observe in Japan is that there is a lot of this cross-dressing and personification of other identities, and what attracts me in particular is how seriously it is taken there. I think for audiences to look at somebody trying to be somebody else is actually quite normal. The challenge then is, what are you trying to be, what can be new about this assumed persona? I’m interested in investigating this urge, or this social acceptance, or even social expectation of assuming different identities.

In a funny way this is also the case in Germany. Somehow, very broadly speaking, I’ve noticed that many Germans like to play games in which they have to be someone else, and to them it’s not embarrassing. I was doing a project asking people to dress up and do karaoke, and they were totally unselfconscious about transforming into something completely alien. I found it really surprising, because aside from an artist like Grayson Perry, British people wouldn’t do that unless they were completely drunk.

All images courtesy the artist.