II. Silent Landscapes Begin to Speak

Wilhelm Sasnal discusses visualizing history and the ‘ethos of painting.’

Moscice 1 (2005), oil on canvas, 100 x 140 cm. Courtesy collection Fundação de Serralves – Museum of Contemporary Art, Porto.

Moscice 1 (2005), oil on canvas, 100 x 140 cm. Courtesy collection Fundação de Serralves – Museum of Contemporary Art, Porto.ART iT: Considering your admiration for Land Art, it seems notable that you have made several paintings about the landscape around Tarnów where you grew up as well as Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus: A Survivor’s Tale and Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 film about the Holocaust in Poland, Shoah. Why did you start making those paintings?

WS: Even though I was born in 1972, I felt that I grew up in a post-war reality. The influence of World War II in this region of the world is inescapable. When you travel through Poland and you see all these monuments, you become aware that this soil has absorbed a lot of blood. You cannot be indifferent to that.

But I also started using historical subjects when I realized that there was something uncool about it, at least for me personally. Prior to that I had been totally focused on youth culture and everyday life, I wasn’t thinking about history and how to use it in art. And then I realized that I wanted to try something that I would find uncool, to address a subject that I wouldn’t have approached before. These paintings were somehow already inside me.

ART iT: Was there anything specific, though, that triggered the switch from youth culture to historical subjects?

WS: I made the switch around the time that people in Poland first began discussing the history in an open way. Prior to the war, Poland was home to one of the world’s largest Jewish communities, and that community was completely exterminated by the war’s end. But in school we learned only that 6 million Poles were killed during the war, no one mentioned that over half of them were of Jewish ethnicity.

These were subjects that had been hidden for 50 years and weren’t really mentioned. But between 1999 and 2003, the Polish edition of Maus was released and Jan T. Gross published his book Neighbors, about the Polish village Jedwabne where in 1941 the Jewish community were massacred by their neighbors. And Lanzmann’s Shoah was broadcast for the first time on Polish TV, so we could finally see the history in a new light.

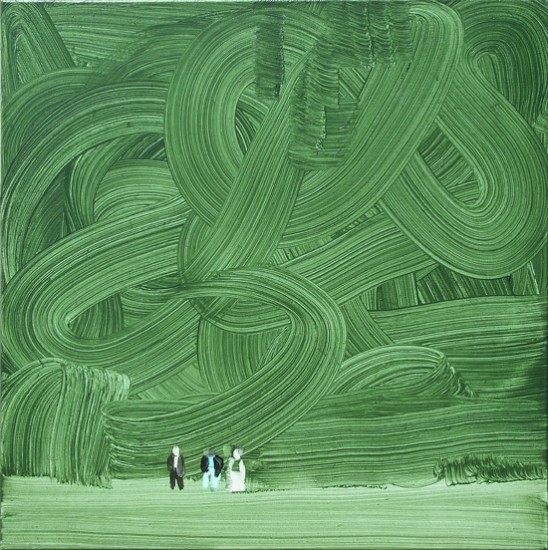

ART iT: But your strategy for the paintings based on Maus and Shoah was indirect, with key details such as figures or facial features removed from images you were referencing. One painting that stands out in particular is Shoah (Forest) (2002), with three small figures positioned in front of a towering expanse of swirling green brush strokes.

WS: Yes, of course. I think Maus and Shoah are important works of art, and I was using these existing works to reconsider the past.

Recently Lanzmann has been back in the news because he has been engaged in public debate with the French author Yannick Haenel about the role of the Polish resistance fighter Jan Karski during the war. Karski, who escaped Poland and testified to Allied leaders about the Nazi extermination camps, was interviewed by Lanzmann for Shoah, and is the subject of a recent book by Haenel. In his book, Haenel accused Lanzmann of editing his interview with Karski, while Lanzmann has countered that Haenel is a historical revisionist. At stake is the credibility of Shoah as well as the relationship between fiction and documentation.

So right before I came to Japan I started re-watching Shoah, which I had recorded for myself when it was broadcast. When I got to this scene with the three figures coming out of the forest, I had to stop the film again; it is such a strong image. The script for my new feature-length film includes a number of scenes that take place in forest settings, and I thought, “This is a scene that has to be there in my own film.”

Shoah (Forest) (2002), oil on canvas, 45 x 45 cm. Photo A. Burger, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth London/New York/Zürich.

Shoah (Forest) (2002), oil on canvas, 45 x 45 cm. Photo A. Burger, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth London/New York/Zürich.ART iT: So when you watched that scene almost 10 years ago it made an impact and even now it is just as strong?

WS: Absolutely. The interesting thing about Shoah is that the film is so selfish. I mean, Lanzmann was so selfish, and I admire that.

Of course in terms of political correctness there is a controversial element to how he made the film, how he approached and interviewed these Polish peasants from the position of a French intellectual. The situation was always in his advantage and he could manipulate it. He knew what questions to ask to get the responses he wanted.

But anyways the film is a work of art. And when you see the slow movement of the camera panning across the silent landscape, it’s so sinister, this void. This awareness of the landscape and what it bears, what’s behind it, or under it, is amazing.

ART iT: I also feel that kind of emotional resonance in your paintings – the sublime feeling of the trees and the tiny figures goes beyond a simple reproduction of an image.

WS: Yes. Behind all my paintings there is a story. That’s why I cannot say that I paint abstractions even if some of them look that way. I have never made an abstract painting; there is always a story behind the visual elements.

Shoah (2003), oil on canvas, 40 x 70 cm.

Shoah (2003), oil on canvas, 40 x 70 cm.ART iT: When you were doing the Maus and Shoah paintings how much thought did you put into choosing the images that you used?

WS: At that time I just responded to intuition. I can predict what images will intrigue me, and what images I can transform through the painting into something that is even more intriguing, even more vague.

What’s interesting is that during the painting process many associations come to me, it’s like a whole story is built up again or maybe put into a verbal language that I speak to myself as I paint. There are these links to the existing works.

Of course, some subjects are really light and I’m not going to overload them with more meaning than necessary.

ART iT: Is there a difference between Shoah (Forest) and your portrait of Robert Smithson, Untitled (Smithson) (2002), or a painting of a toilet in a bar in Kraków?

WS: In terms of the approach to the subject, not so much. Sometimes when I want to play with existing materials or a certain form there are differences, but I treat painting very seriously. When I have the feeling that the painting is done, I leave it. I never leave the painting when I have doubts about it.

I’m never so cynical to think about a painting, “Maybe it’s not OK, but it’s going to sell anyway.” I am responsible to myself. I believe in an ethos of painting.

Lata Walki (2005), oil on canvas, 150 x 190 cm.

Lata Walki (2005), oil on canvas, 150 x 190 cm.ART IT: But clearly your definition of when a work is finished is quite broad, since in your text painting Lata Walki (2005) you ended up cutting out the words from the canvas entirely.

WS: That was fun. Lata Walki, meaning “Years of Struggle,” was the title of a chapter from a stupid Polish war film. I really liked that phrase, and thought it was meaningful. I tried to paint it several times but the letters never looked right. I really struggled with the painting. I over-painted the text two or three times before I finally gave up and cut the words out.

I’m increasingly attracted to the ugliness of painting, making mistakes, collapsing. It’s partly a reaction to what I don’t like in contemporary painting.

Painting is a tough job. I could never be only a painter. Maybe that’s why I also need to make films. I’m afraid of approaching painting on my knees, of trying to be a master, because I think it’s a waste of effort. How many paintings can you paint to prove to yourself that you’re a master – that you’ve achieved what you wanted to achieve?

Rather than trying to reassure myself, it’s more productive to doubt myself about what I do. It’s also a reaction – not necessarily to the market, as such – to how painters try to make catchy pieces that will be noticed by the audience. Of course I understand that I’m also saying this from a privileged position.

ART iT: One thing that interests me is that you’ve generally resisted the urge to make monumental canvases.

WS: I think the biggest work I’ve made is 2 by 2.2 meters. That’s fairly big, but actually I cannot make anything bigger because it wouldn’t fit through my door. In any case it’s not a particular desire of mine.

This goes back to my previous answer: I never assume that I’m going to paint a masterpiece. I work with the canvases that I have. Amid the current flood of images in our society, I think painting is in a very special situation compared to previous ages when it was the only way to depict the world.

I’m not so naïve to believe that painting can change the world or change people, because it is no longer a medium of “mass destruction,” as film can be. Because we have become blind to the images around us, and are so fed up with them, I think it actually returns painting to a position similar to what it occupied in the past. It’s a way to turn images into something physical.

Unless otherwise noted, all images courtesy the artist.