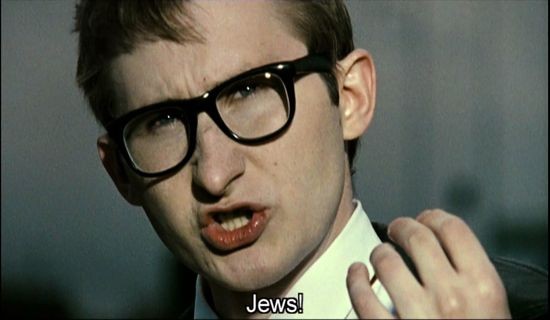

Production photo from Mur i wieża (Wall and Tower) (2009). Photo Magda Wunsche & Samsel. All images: Unless otherwise noted, courtesy Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, and Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv.

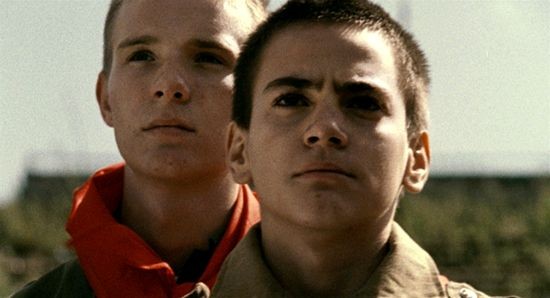

Production photo from Mur i wieża (Wall and Tower) (2009). Photo Magda Wunsche & Samsel. All images: Unless otherwise noted, courtesy Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, and Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv.Currently living between Berlin and Tel Aviv, Yael Bartana has been selected to represent Poland at the 54th Venice Biennale in an exhibition entitled “…and Europe will be stunned.” Bartana has long dealt with issues related to life in Israel in her works in video and other media; it could be said that this interest is indeed what led her to begin a trilogy of short films shot on location in Warsaw imagining the activities of a quasi-fictitious organization seeking the return of three million Jews to Poland, the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland (JRMiP). ART iT corresponded with Bartana to discuss the JRMiP trilogy, which will form the core of the Polish Pavilion, and why it is necessary to critique nationalist agendas.

Interview:

ART iT: Previously you’ve made works that address aspects of Israeli society and politics, and now you are working towards the completion of your trilogy of films about the quasi-fictitious Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland (JRMiP). Has your selection to represent Poland at the Venice Biennale changed anything for you in terms of how you view your work, or your approach to national identity?

YB: I wouldn’t say that it’s changed how I view my works so much as it has created a situation where my fiction has become a reality. For a long time I have been interested in moving beyond the bubble of the artworld in order to touch reality in a more direct way. Being selected to represent Poland has allowed me to cross that border between art and reality or fiction and reality. This is the biggest success for me in a way, this realization of my vision – my fantasy – of dealing with real issues through the tools of art.

ART iT: And the JRMiP also has started to take on life beyond the project, is that correct?

YB: Yes. In 2012 we will hold a congress in Berlin as part of the Berlin Biennale. I’m working closely on the concept with the Polish artist and filmmaker Artur Żmijewski, who is the biennale director. The JRMiP generates a lot of curiosity. I gave a presentation on the movement at the Berlinale film festival in Berlin last February, and the audience asked many concrete questions of me – for example, how the movement would deal with property rights. There is a serious demand to deal with real issues, and high expectations for the movement. But I think the metaphor and the symbolism behind the idea are important to maintain, so the biggest challenge is to find the right line between the real and the fictional, to find a way to deal with the two worlds and to play with that.

The members of the movement are not necessarily Jews. It’s not my intent to limit the project only to issues of Polish Jews. This is a very specific study case but it touches upon more universal issues that reflect on social changes and migration in Europe and Middle East, and the possibilities or impossibilities of living with others, and the extreme nationalism and racism that is everywhere and currently increasing. It’s important for me strategically to deal with something very concrete, with the history and the current situation between Israel and Poland or Jews and Poland, but the project can also speak for other nations.

Both: Video still from Mary Koszmary (Nightmares) (2007). Courtesy of Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw.

Both: Video still from Mary Koszmary (Nightmares) (2007). Courtesy of Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw.ART iT: Your works can have an alienating effect on viewers, in part because of the specificity of the subject matter and also because you appropriate strategies of propaganda film in their composition. It is difficult to sympathize with the subjects of the films – whether Mary Koszmary (Nightmares) (2007) or Mur i wieża (Wall and Tower) (2009) – nor is it possible to wholly sympathize with the eye of the filmmaker. But this actually can prompt reflection on one’s own position with regard to nationality and its underlying issues. Is that an objective of the work?

YB: Rethinking nationality absolutely has been my main topic for the past decade – the issue of constructing an identity through nationalism and how that is symbolized and communicated. Nationalism is an imaginative and manipulative way of creating a sense of belonging, and I think the JRMiP employs that as well. But I’m criticizing fascism even as I use elements that originate in fascist aesthetics. Probably this can be confusing for viewers, but I wish to create optimistic conditions, not oppressive conditions. The aesthetics of propaganda I find to be very powerful, direct, communicative and simple, which allows everybody to connect to the work on some level. At the same time those images are also registered in our collective memory, related to a very different and negative history. It’s my strategy also to flip these relations. I think that’s where the artistic element comes through. Only in art can you allow yourself to mix emotions in that way.

ART iT: For example, where do your sympathies lie in a film like Mur i wieża?

YB: The film is a criticism. It is a criticism of a positive utopia that turned into a tragedy. I think it underlines the tragedy of nations and, specifically in the case of Israel, the tragedy of the utopian idea of creating a safe place for the Jews, which has led to the complete erasure of another culture. I see the project as a mirror that reflects back the images of Europe and the Middle East. My hope is to develop it further, not to only position myself in terms of criticality, but also through the congress at the Berlin Biennale to propose something – first of all to propose that politics should not stay only in the realm of government.

Both: Video still from Mur i wieża (Wall and Tower) (2009).

Both: Video still from Mur i wieża (Wall and Tower) (2009).ART iT: As suggested by the questions you have received about how the JRMiP would deal with property rights, the outrageousness of inviting three million Jews to return to Poland also seems to underscore the complacency with which we accept the default conditions of political agency. It seems like it would be a natural reaction even for liberals in Poland to completely reject the idea of inviting three million Jews to return.

YB: Fanatics on both sides are going mad from this project. I have received many negative critiques from both Poles and Israelis who take the project literally. There are people who are horrified that the proposal might actually be realized and that suddenly there would be a massive return to Poland of Jews who would take over the land and positions in the workforce and run the economy. And then in Israel, so many Jews leaving for Poland would lead to an opening for the Palestinians to return to their homes, so there is this additional aspect of right of return involved in the project.

ART iT: Your earlier videos were often anthropological or even structural in their composition, and then around the time of Summer Camp (2007), following a group of Israeli, Palestinian and international volunteers as they rebuild a Palestinian home that was destroyed by Israeli authorities, you shifted toward a more cinematic vocabulary. What triggered that shift for you?

YB: It’s difficult for me to answer. I think it’s related to my fascination with propaganda films. For a long time I wanted to create a dialogue with those early propaganda films – specifically Zionist films but not limited to that – because I think they are aesthetically very strong, and also because I thought it could be a way to directly discuss the tragedy of the state of Israel. It started actually with the film A Declaration (2006) [in which a man rows to Andromeda’s rock in the harbor of Jaffa, and replaces the Israeli flag that flies there with an olive tree]. That was my first attempt to deal with those early films, working with more narrative and less abstract elements. It has slowly developed from there.

ART iT: Are you doing anything differently with the new film, the last in the JRMiP trilogy?

YB: I think you cannot watch the third film without first knowing the first two films, because it is about the assassination of the leader of the JRMiP. It’s about his death, and it’s an attempt to make the idea of the return to Europe more complex. It incorporates more voices – even Zionist voices – and there is another layer that talks about the ghosts of the six million Jews.

ART iT: What is your relationship like with the actors who participate in the films?

YB: In Mary Koszmary, the man who gives the speech inviting the Jews to return, Sławomir Sierakowski, is not an actor. He is an activist, journalist and philosopher who is trying to create a new Left in Poland. When I was doing my research in Poland I was looking for a collaborator there who believes in shaking up the status quo. He believes in the project, and he believes from his heart that the return of Jews and other minorities is necessary for the culture, because after the war Poland became such a homogenous society. For me he is not an actor, he’s a figure or a protagonist who is dealing with the issue in real life as well as in the fiction. So as I said there is a thin line between the fictional and the real for me. For the new film I have also invited a Holocaust survivor to give a speech, as well as an art historian who is considered a minority, and who speaks about the possibilities of minorities living together in Poland. All the people involved in the project understand what I’m trying to do even if they don’t necessarily believe such a project is actually feasible.

Video still from A Declaration (2006).

Video still from A Declaration (2006).ART iT: You have dedicated the past decade to confronting issues of nationalism through your works. Why do you feel it is necessary to do so?

YB: In terms of Israel, the danger of nationalism is that many people have been brainwashed and tend to think in a close-minded and conformist way. It’s very simplistic. They are not able to understand complexity or the perspectives of others. It is a kind of damaged mentality, very scary, very aggressive and violent, and one that supports extreme power. Certainly I think every country should be able to protect itself, but for me the situation in Israel goes beyond the whole idea of Judaism and extends to issues of territory and diaspora and the changes that happened with the creation of the state of Israel. I’m trying through my artworks to learn about these issues and to be very open about my feelings. Even if they look didactic, for me it’s a way to create a discourse. I know my works can be provocative, but even if I’m insulted, if I can cause people to speak out then it allows me to see the diversity of society.

I can’t make promises about how long I will continue this approach but I can say with regard to the current project in Poland it’s been extremely interesting to also work in a country that is connected to Israel in a very specific way. For most Israelis, Poland still represents the Holocaust, because that’s where most of the Jews were killed. Yet I’m also aware it’s a very risky project. Sometimes I have fears that I am the one who will be assassinated.

The 54th Venice Biennale, “ILLUMInations,” opens to the public June 4 and continues through November 27.

Return to story index

Venice Biennale – ILLUMInations: 54th International Art Exhibition