New songs without words: Yurie Nagashima’s ‘SWISS+’

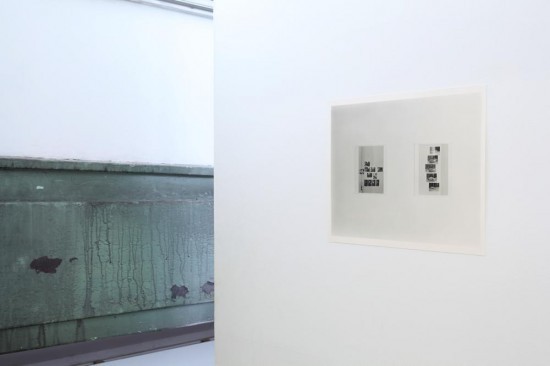

All images: Installation view of “SWISS+” (2010) at SCAI The Bathhouse 2F View Room. Photos Keizo Kioku, courtesy SCAI The Bathhouse.

All images: Installation view of “SWISS+” (2010) at SCAI The Bathhouse 2F View Room. Photos Keizo Kioku, courtesy SCAI The Bathhouse.It was 1994 when I first met Yurie Nagashima, soon after she won the Parco Prize for a series of photographs of herself posing nude with her family. (Nagashima had made the photos after she was inspired by the work of Nobuyoshi Araki on display at the “Urbanart #2” exhibition held at Shibuya Parco the previous year.) At the time, I’d been asked by Takaaki Akita to organize an exhibition at P-House, the gallery he ran out of his own one-bedroom apartment not far from the old Tower Records, also in Shibuya. I strongly recommended Nagashima, then a student at Musashino Art University with no solo exhibition history whatsoever. The result was “Nagashima Yurie – A Room of Love” (1994), the second exhibition at P-House following an exhibition of Kyoko Okazaki organized by Hideto Fuse. At the opening party, which was held at a separate venue and attracted a huge crowd on account of P-House’s status as the latest contemporary art venue to open in central Tokyo after Roentgen Kunstinstitut (in Omori), a band I’d impulsively started up with Masaya Nakahara and Kiki Kudo among others performed, but during the first number Nakahara’s snare drum broke and everything fell apart, bringing our activities to a close – the last that was heard of us being Nakahara yelling, “Let’s call it quits already!”

As for the all-important solo show, as P-House was a gallery in name only, the reference in the title to a “room” rather than an exhibition was spot on. Nagashima filled the tiny living room exhibition space with dark pink feathers before adorning it with her photographs. The overall impression was of a harlot (played by the artist) divulging an intimate secret to visitors one by one.

Because those times made such a vivid impression on me, even now when I think of Yurie Nagashima, much of what comes to mind is based on that experience. I’ve met Nagashima numerous times since then, but the other day when I went to see her latest solo show, “SWISS+” at SCAI The Bathhouse, I was suddenly overcome by a strange sensation in which scenes from “A Room of Love” flooded back to me and were superimposed over the exhibition before my eyes. Of course, I had learned from hearsay of Nagashima’s accumulated experiences over the intervening years, including her sojourn in the US and her having been presented with the Kimura Ihei Award for photography. And yet despite this, when I viewed “SWISS+” I felt that it was unmistakably “A Room of Love,” albeit in a different form.

Let’s briefly review the order of things. First, this exhibition was based on the already published photobook SWISS. The book features photographs of interiors and garden vegetation taken in 2007 when the artist lived for a short time in the small Swiss town of Estavayer-le-Lac as part of the Laboratoire Village Nomade residence program. But it is more than a mere collection of photographs. The basis of the book is the artist’s changing frame of mind concerning her relationship with her son, who came with her to Estavayer-le-Lac. These changes are reflected in the vegetation and interior scenes and give rise to an astonishingly melancholic sentiment. Nagashima had input into both the production of the book and the choice of color on the cover, and the resultant publication, in which the quality of the paper stock changes regularly depending on the subject matter in a way that also functions as a vehicle for the artist’s “diary,” perhaps should be called a new type of illustrated book rather than a photobook.

Such being the case, there was no way the “SWISS+” exhibition would reproduce the kind of simple substitute whereby photographs are presented to coincide with their publication in a photobook. The seemingly commonplace photographs of flowers decorating a living room originally included in SWISS were taken 25 years ago by Nagashima’s grandmother, who has since passed away. During her sojourn in Switzerland, Nagashima stuck these photographs to her wall and re-photographed them as contemporaneous scenes. Captured with the scenes from 25 years ago nested within, the living room in Switzerland containing the grandmother’s photographs of flowers also serves as a vehicle for manifesting in the present these memories via Nagashima’s photographs. Which is to say, the suggestion of traveling in time and space that was already apparent in condensed form in the photobook was also apparent in the exhibition, although this time emphasized to a far greater extent.

In addition to these photographs, the walls of the exhibition venue were decorated with other items including a reflective plate that presented visitors with a quasi-mirror image of themselves, and a slow-moving video shot from the window of the room in Switzerland. Additionally, black-and-white photographs of some of the items on the walls in this exhibition were themselves attached to the walls, further exaggerating the nesting of space-time and throwing into confusion the viewer’s sense of space and time. In what kind of space-time are the photographs that we just saw positioned in relation to the scenes in the photographs at which we are looking now? With this question in mind, and troubled by the gap between this and their typical viewing experience according to which nothing strays from the present of 2010, viewers must constantly re-adjust the focus in their minds as they wander around the small room. It is precisely this “wandering,” which stems from the fluctuation of memories and the fluidization of the fixed point of “now,” that defines “SWISS+.”

Given this, why did I still feel it was “A Room of Love”? In 1994’s “Room of Love,” Nagashima appeared alongside the members of her family. What tied this group of naked people together was clearly a kind of familial love, or relationship of trust. At the time, regardless of how sensational the portraits appeared, the “Room of Love” was reinforced by an unshakable sense of security, and one could say that this neutralized the excessiveness of the images of the naked family, images that were eccentric and even suggestive of incest. With “SWISS+,” however, the family includes members who have passed away, and for the artist living in a foreign country, dislocated from the group of which she is a member, the family is something to be presided over as a temporary vessel for the purposes of raising her son. That the strong suggestion of the family in “SWISS+” only reaches the shadowy self (ie, the viewer) via a quasi-mirror-like screen that does not reflect people but in fact serves as a field of projection for one’s own memories is probably not simply because the exhibition depicts the passage of time, but also because it deals with the difficult question of how to represent, via photographs, not “relations” but “the breakup of relations.” Nevertheless, regardless of how completely it has been transformed into a room in which people are absent, even this sense of absence is supported by none other than a yearning for people and feelings of love. One can only conclude that in contrast to SWISS, which was endowed with words, what Nagashima is striving for in “SWISS+” is a kind of song without words.

Yurie Nagashima‘s “SWISS+” was on display at SCAI The Bathhouse, Tokyo, from July 2 to August 4.

Archive

Noi Sawaragi: Notes on Art and Current Events 1-6