II. Retrograde Parlor Tricks

Yeondoo Jung on the illusory limitations of digital effects.

Location #5 (2006), C-print, 116.8 x 240 cm. All images: Courtesy the artist and Kukje Gallery, Seoul.

ART iT: We were just talking about your two video-performance pieces Documentary Nostalgia and Cinemagician, and how they comment on technology by, in a sense, misusing it. Have you made other works that directly comment on the medium you’re using? How about your photographs, for example?

YJ: The “Wonderland” (2005) series of photographs recreating children’s drawings has a lot to do with the replication of reality. At first glance a photograph looks like real life, but as a representation, say, of a street scene, then there are many other unavoidable elements and contexts that enter into it. It’s not just a street, it’s a suburb of Seoul; it’s not just a person, it’s always someone. But a child’s drawing always has a remove from reality. Children don’t understand the relations between scale, composition, color, the laws of physics and other elements that inform our representations of reality, whereas in photography all of that is automatically accounted for. You could almost say that the medium of photography and children’s drawings are diametrically opposed. One is a very realistic mode of representation and the other is the most unrealistic possible. I thought there was a lot to play with in combining these two extremes.

Then with my “Locations” (2007) series I thought about the 17th-century Dutch painters. They painted these landscapes that were influenced by images of Spain, with mountains, hills and rivers, but if you go to Holland everything is flat. So they created their landscapes in the studio, out of their imaginations. Yet, a landscape photograph always relates to the limitations of the medium. You have to bring a camera to some kind of extraordinary or specific location, and then which moment you press the shutter at which angle determines the resulting image.

Now that everybody has a camera, if something amazing happens on the street somewhere, it’s far more likely that everybody on hand will take out their cameras and photograph it than it is that anybody might take out a notebook and sketch it. Even in the 17th century when painting was at its peak, I don’t think the average person would have sketched a noteworthy event. Photography is a representational medium that is shared by an extraordinary number of people, and the specific beauty of the place or the particular moment you press the shutter is no longer as definitive as it once was. And photography is such a realistic medium that once people understand an image in terms of where it was taken and how, they lose interest in it. My response was to bring the studio lighting system and props to the landscape, creating confusion between the real natural setting and an artificially constructed backdrop.

As with Documentary Nostalgia, my way of dealing with a realistic medium was the opposite of how people normally deal with it, and the most inefficient way I could possibly think of.

Above: Location #11 (2006), C-print, 122 x 155 cm. Below: Location #1 (2006), C-print, 122 x 153.5 cm.

ART iT: But when we talk about everybody having cameras, we can also think of writing as another important technology that was for a long time the domain of only an elite few, and is now widely shared – and of course in Asia the official literacy percentages in China, Japan and both North and South Korea are all above 90 percent. Maybe that’s where photography is headed, where it’s no longer about being impressed by the image itself and people begin to appreciate a kind of “deep literacy” of reading what is behind the text or behind the image.

YJ: There are certainly still many things in both literature and photography to explore. That’s why I keep making artworks.

Another thing I find important is that technology is always one step ahead of the artist. It takes time to humanize technology. It takes even longer to find a way to express lasting values through new technology.

In fact I actually do use cutting-edge technology in my works, but on a completely superficial level. It’s almost like a 1970s guy who has been inserted into the present. Where you could easily solve a creative problem by simply pressing a button, I end up doing everything myself. In any case I shot the entire 85 minutes of Documentary Nostalgia using a digital recording device, because film doesn’t have the capacity for recording something that long in one take. I connected a computer hard drive to the camera, so the camera was not recording to tape or any other medium, it was recording directly to the hard drive, and in turn the hard drive was copying the file into the computer directly. This was only possible with the development of faster connecting cables and faster camera capturing speeds and faster computer chip processing speeds, and everything was in high definition. None of this technology had been available to anyone before. Even in 2007 I was barely able to handle this media. But otherwise everything about the production of the work was very manual and physical.

I think artists should not be overwhelmed by technology. For instance, I am a big fan of Harry Potter. I actually memorized all the spells, I read the books many times and had a cassette tape to repeatedly listen to the audio versions in my car. In the first book, Harry is living as an orphan with his relatives in a closet under their staircase, and he feels completely worthless. Then the invitation from the Hogwarts school arrives and he finds a new dignity and reason to live. This feeling was conveyed beautifully through the writing and does so much to build the fantasy of the story. But when the movie came out and the computer imagery made this fantasy possible for the screen, and we could see the castle and the train and people flying through the air playing quidditch, none of these roller-coaster effects zooming in and out could actually convey the sense that this little orphan Harry had discovered his own specialness.

This isn’t necessarily about distinctions between literature and movies, but technology is not always the solution to expressing these complex human experiences.

Bewitched #2 (2001), C-print, 120 x 150 cm.

ART iT: Advances in CGI technology have led to a new boom in Hollywood of recycled fantasy classics like Chronicles of Narnia, Lord of the Rings and Alice in Wonderland, as though every generation has to reinvent these stories for its own technology. But one thing that these movies all seem to over-emphasize – and I think this is related to the special effects – is the notion that the characters cannot grow without killing something. This is always justified as resulting from a battle between supreme good and supreme evil, but it’s really surprising how deeply fascist the Hollywood fantasy genre is, whereas perhaps the original books at least had more complexity.

YJ: When I was a child there was a puppet program on TV that had a witch puppet flying on a broom, and there were always shreds of paper waving back and forth to evoke clouds, and a fan in front of the stage to blow the witch’s hair everywhere, and since the puppets couldn’t move their legs, when they walked they simply bounced up and down as the puppeteers move them back and forth. I think this kind of puppet story is in a way more sophisticated than CGI, even though it has less detail and people know it’s not real because they see everything holding the fantasy together. Computer effects may be believable, but in contrast to the puppets, few people have any idea how the effects actually work. This difference between knowing or not knowing the roots of the process is very significant to the emotional attachment viewers invest in a work. If you don’t understand the illusion you can be swept away by the effects but also alienated at the same time.

Another example is my photo series “Bewitched” (2001), in which I helped people to realize their fantasies. Each work in the series comprises two photographs, one taken from the subject’s everyday life and the other of the subject living out a personal fantasy, with the subject in the exact same pose in both images. The “Bewitched” series was inspired by the American TV series of the same name, which I watched when I was a child. In the TV show, when the witch Samantha twinkles her nose, something magical happens. But even as a child when I saw these scenes I understood that the producers had simply stopped the camera and changed the set, then moved everyone back into the same position. You can recognize it immediately, but the effect was amazing.

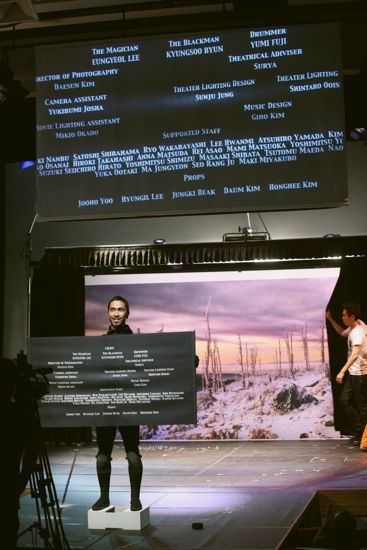

Both and following image: CineMagician (2010), dual-channel HD video, 55 min.

ART iT: Did you ever see Alexander Sokurov’s film Russian Ark (2002), which was shot in a single 96-minute sequence shot at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg? The difference between this film and Documentary Nostalgia is that the camera is moving through space, and the characters are moving with the camera, so it’s not a stationary composition.

YJ: I haven’t seen it, although it sounds interesting. But this actually reminds me of a point I wanted to make about CineMagician. The title refers to George Méliès, one of the first explorers of filmmaking in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Before cinematography was discovered, people like the Lumière brothers shot these documentations of real life, with people walking around the streets or workers coming out of the factories. I think Hollywood movies were built around this documentary approach, and of course dramas tend to resemble everyday life and experiences. Méliès, however, started out as a professional magician, and he wanted to use film to create a fantasy world, even building a glass studio with white linen curtains to control the sunlight. He made hundreds of films, including Trip to the Moon (1902). All of them were amazing, but what I find really interesting are the special effects that he made through double exposure techniques. He would take his neck out and hang it somewhere, or transform into a woman and then back into a man, or grow large and then small again. All these effects are so primitive. If you see the films today you can recognize that he’s walking close to the camera to grow large and then standing away from it to grow small. It’s an illusion but so much of the mechanism remains visible.

I worked with a professional magician on CineMagician, and we agreed to switch roles for the work. I put myself on the stage, acting as the magician, and he played the role of the artist. As my alter-ego, he had to build these sets recreating beautiful scenes that I remember from my 20s when I was in a mountaineering club. But the way he went about doing this was not logical. In fact, it resembled the way artists work. He used some of his magic props such as the levitating table. Usually in a magic act he might have a beautiful lady lying on the table to complete the illusion, but in this case when he needed to use the table leg for something else, he just took it out from under the table and started working on other things. The result is that many people who saw the work didn’t recognize which part was magic and which part was not. Everything was illogical because it was all going against the laws of gravity, but people didn’t recognize it as magic or something out of the ordinary. So CineMagician plays with these visual tricks that are both amazing and yet widely known, but the interesting thing is that people actually were enchanted because they didn’t recognize what they were seeing as “magic.”

The work of Yeondoo Jung is currently on view in the 8th Shanghai Biennale, “Rehearsal,” at the Shanghai Art Museum through February 28, 2011, and in the exhibition “Made in Popland,” at the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea, through February 20, 2011.

Part I. Advancing Beyond Efficiency

Yeondoo Jung on how the misuse of technology leads to art.