IMAGINARIUM (1981)

The below is a revised translation of the version of this text that appears in English and Japanese in the monograph Yamaguchi Katsuhiro 360º (Rikuyosha, 1981).

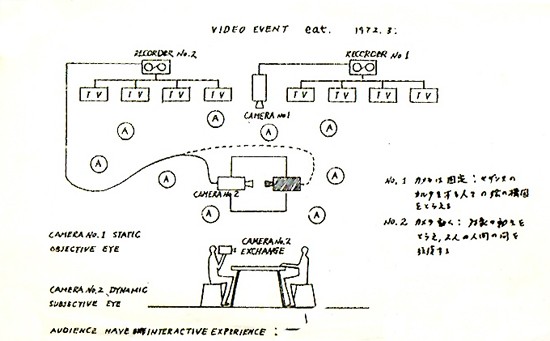

Diagram for the video performance Eat (1972), conducted at the exhibition “Video Communication: Do-it-Yourself Kit” at the Sony Building, Tokyo, 1972. All images: © and courtesy Katsuhiro Yamaguchi.

Viewed sociologically, Modern and contemporary art have their beginnings in the product concept as so-called “work of art” that emerged in the capitalist social system. Then, for commercial purposes, the veil of mystery was thrown over the very concept of art, followed by the mystification of the contents and expressive method of the work, obscuring the potentiality of interpretation. The mass media, without addressing the mystery of art itself, took on the role of popularizing that mystery for the sake of profit.

The reason the pictorial print system, while making possible the popularization of art, did not prove to be a denial of what Walter Benjamin described as the cult value of art was because the means of popularization was nothing but an arithmetic division of the scarcity value of the original, and still relied on the same cult value. The fact that prints have already obtained an aspect of Benjamin’s cult value simply means that the value itself has been divided, or multiplied. From the middle ages, the print workshop system had been a socially integrated system for reproduction media, but with the approach of modernity it became restricted to the reproduction of art.

Consider the existence of reproduction media in society and how their function relates to art. At present, the print system has already lost its function as a social medium, but the electronic copying system has the potential to serve just such a function. Our use of electronic copying devices is predicated on the infinite volume of copies that can be made from just one copy. Furthermore, the cost per copy has as its standard the unit price, the same as with the cost of telephone calls. However, although copies are material products, viewed from the perspective of information media the copy is not so much a product as it is a process medium.

Inherently related to process media, art must be accessible when and where it is necessary to the people who require it. In my opinion, the denomination “art” itself should be eliminated and replaced by the term “imaginary performance.” I envision a fundamental system in which the imaginary performance passes through process media and is then transferred as information to the people who require it. In this case, such people should be thought of as “assessors” rather than “recipients.”

On the basis of the above considerations, my proposed concept of the “Imaginarium” can potentially be realized through the following two directions:

One addresses the issues involved with the form of a work of art. In order to make the Imaginarium more concrete, in 1972 I developed the idea of Info-Constructive Sculpture. This idea took shape in the “video exercise” Las Meninas (1974-75), in which I re-interpreted Velázquez’s famous work of the same title through a video media system. Here, the incorporation of the spectator’s act of viewing into a real-time site transformed Velasquez’s painting into an information environment.

The Las Meninas exercise served the purpose of enabling me to better understand the function of video media. However, my environmental work that further develops the utilization of feedback in an information system is the “Project for Flame-Water Fountain,” conceived in 1974 [never realized]. In this work the spectators, just as the flames, water and steam captured by the video cameras, would become an image of a part of the environment. In this way the spectator, whose position in the case of Las Meninas was strictly that of the viewer, would be more actively incorporated into the composition of the environmental sculpture.

In contrast to the above methods of implementing the Imaginarium through an open environment, the following work is an Imaginarium that deals more with sculptural space.

Among the characteristics of 20th-century sculpture, the most significant is the transition that occurred from forms of volume and mass to those of space. That is, the interior of a sculptural work was no longer closed off and invisible, and became a space that could be seen through from the exterior. The Info-Environmental Sculpture that I next plan to exhibit incorporates an information circulation using video cameras, video tape recorders and monitors built into a sculptural body. In this case, the sculpture itself has the function of simultaneously seeing the spectators and being an object to be seen, while spectators similarly have the function of simultaneously seeing and being seen.

Spectators standing before the sculpture look at it. However, the camera built into the sculpture constantly records them, with those images fed into a monitor that is inside the sculpture and thus out of view. The sculpture’s interior is lined with mirrors, and another video camera constantly records the information environment therein. The images from the second camera in turn are fed to a monitor outside the sculpture, allowing spectators to see the information environment that exists on the inside.

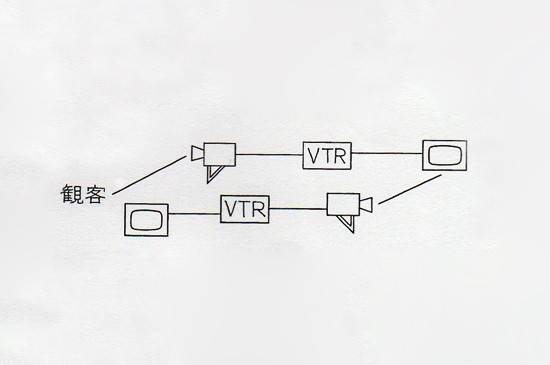

This Info-Environmental Sculpture will comprise the following system:

[In the above diagram, the position of the viewer is indicated by the Chinese characters at far left.]

Whereas the architect Frederick Kiesler once proposed an “Endless House,” this sculpture can be considered an “Endless Info-Sculpture.”

If in this way the concept of the Imaginarium is able to transcend conventional sculpture, it also makes possible a reevaluation of how art museums function. André Malraux’s Musée Imaginaire sought to revise the contents of European art museums since the Modern era – limited to representing a Eurocentric system of art history – through the extensive addition of non-European world art. Regarding Malraux’s methodology, the art critic Atsushi Miyagawa has commented that it proposes a monumental systemization of art theory based on an awareness of “quotation.” Miyagawa states, “[to do so] is to sever the work from its intrinsic temporal and spatial context and bring it into a new context.” Miyagawa further states, “If Malraux emphasizes the role of reproductions as complementing art museums, it is because the function of reproduction media is precisely that of quotation from the original. The same as, or even more so than do museums, reproductions make possible the comparison of works of different times and places by severing them from their intrinsic contexts.” As Miyagawa has noted, in his Musée Imaginaire Malraux puts practical emphasis on the concept of quotation, but since the time of Hellenism hasn’t the original premise of the art museum been the concept of quotation?

The issues related to a “quotation” that severs a work from its intrinsic temporal and spatial context and a “copy” based on an original work constitute the central theme in the art museum discourse, though from a viewpoint that differs from the example of pictorial prints mentioned above. For instance, Kiesler objected to the idea of “quotation,” and proposed returning the works from the collections of all museums to their places of origin. An environmental artist who prioritized the relations between works and the environments to which they belong, Kiesler regarded the establishment of European museum collections by looted properties as a kind of cultural plunder. As a remedy, he proposed “home museums” that would be decentralized rather than centralized, whereby private homes maintain collections of a few paintings each, which viewers could visit one by one. Preceding this grassroots-type proposition, Kiesler had also raised the idea of “telemuseums” (1929). In this proposal related to “copies,” or rather, reproduction media, Kiesler foresaw an electronic transmission system for works of art that would utilize cable television, with works transmitted upon request from institutions like the Prado and the Louvre.

Now, 50 years later, Kiesler’s profoundly insightful proposal is finally on the threshold of realization. These imaginary museums will deal with works of art. However, those works of art, as with all the other artistic activities, will be the result of imaginary performances.

If the function of an art museum is quotation, then selection and synthesis are aspects of this function. What art museums are executing under the name of “collecting” is none other than the systematization of art history. The reason art museums are fixated on processes of editing and systematization that revolve around works is that they lack any capacity to respond to imaginary performances. However, we are now living in the age of electronic media. Why are art works alone dealt with as products? Art has always been linked to process media. The remarkable progress of visual media in the 20th century has enabled us to understand art through the act of viewing, and not only as a work. Both creators of works of art and the recipients of those works can now be linked in the same contextual field in terms of viewing. It is this series of actions that constitutes an imaginary performance.

Employing video cameras and video tape recorders, these imaginary performances indicate the exact direction for which 20th-century visual arts are headed. As mentioned above, the plastic arts of the 20th-century have intensified our consciousness of space. However, visual media centered on video have given more profound meaning to the act of seeing, and the variety of images is now open to any kind of source. Even images that have passed through information media are not exempt. The question lies not in the fact that these images have been quoted, but in through what information media and by what operation they are quoted. To go a step further, it lies in how the viewer is involved in these operations and by what means the multilayered viewing has been carried out.

Even in the field of video art, with its already 15-year history, video media have played a role in making our viewing more multi-layered. Further, as with other media, video is deeply involved with its peripheral media such as the cinema, the photograph, the photocopy and so forth. The videodisc, which will be introduced in the 1980s as yet another new visual medium, is closely related to the visual media that preceded it. At the same time, unlike videotapes, this new medium will enable random-access searches for information.

However, I believe that for the purpose of expanding human physical capabilities, video equipment – including cameras and recorders – will play an even greater role in the artistic field of performance. In the Imaginarium that I have in mind, while activating the respective characteristics of such visual media, we will have greater access to a broader spectrum of art. The process of transmitting the imaginary performances created by the Imaginarium through prepared media to what I term “assessors” is as follows, as understood from the two aspects of space and activity:

1. Since the Imaginarium is a network of media in space rather than a specific place, there are no preconditions for its scale or the nature of its equipment, as long as it can be a site where the space and media necessary for an imaginary performance are provided. Utilizing the provided media, anybody, whether alone or in a group, can create a work on themes ranging from one’s own society, environment and life to artistic expression and so on. Further, the prepared media can be used for the formation and simulation of imagination as well as the transfer of images, while images thus acquired can be recorded on the prepared media. It is also possible to variously alter the original images through the use of microfiche, videotape, photocopying and so forth. The Imaginarium can also serve others in their research.

2. If such a space is considered from the viewpoint of a performance, the Imaginarium has a precedent in the traditional collective art forms of Japan such as renku or renga gatherings for improvised poetic composition. In particular, renku gatherings were held spontaneously at venues such as private homes, with an emphasis on live communication. According to [Matsuo] Basho, it was the live atmosphere of the site of the gathering that was more important than the verses that resulted from the expression of renku. He wrote that at the conclusion of a renku gathering, the sheets of paper documenting the poems should be thrown away. This lively function of a collective imaginary workshop must be reflected in the Imaginarium.

3. Another important point of development for the Imaginarium will be its use of the satellite communication system. Included in this plan is the connection of local Imaginariums by the satellite communication system. This will eliminate the cultural hierarchy that results from centralized artistic and cultural activities, and therefore is a necessary means in preserving the specific attributes of local art and culture.

If one considers the exchange of information on city planning and architecture, or the enormous expenditure for transportation involved in exhibiting large-scale sculptures and artworks, a satellite-based artistic information network will play an even more crucial role in the future. There are too many restrictions on the utilization of the communication satellites presently orbiting the earth to be able to respond to such demands of the times. Therefore my thinking is that it is necessary to launch an “Art Satellite” to use for artistic purposes, just as there are satellites that are devoted exclusively to meteorology or military strategy. Should the world’s art museums and art professionals agree [to cooperate], the costs for launching an “Art Satellite” should be procurable.

The above-mentioned project concepts, when consolidated, will enable the Imaginarium to function as a global information network that goes beyond the function of conventional art museums and galleries. Above all, earth’s cultural heritage of relics and ruins is not the exclusive domain of archaeology, history and tourism. When the Imaginarium network is implemented, greater events incorporating video projection, laser shows, large-scale holographic projections and so forth, as well as music and dance, can be held at such sites. Such comprehensive performances can be relayed across the world via the “Art Satellite,” and, as required, events can be fed-back via satellite from local Imaginariums.

The significance of such performances will not be limited to that of art alone, but will also serve humanity in expanding its consciousness into the past and future in a cosmic perspective.

*Author’s note: This thesis consolidates essential points about the Imaginarium concept that have been published since 1974 both abroad and in Japan in forums including magazines, reports and exhibition statements.