III. A Good Judge of Character

Isaac Julien addresses the stakes of Orientalism and his use of politicized aesthetics.

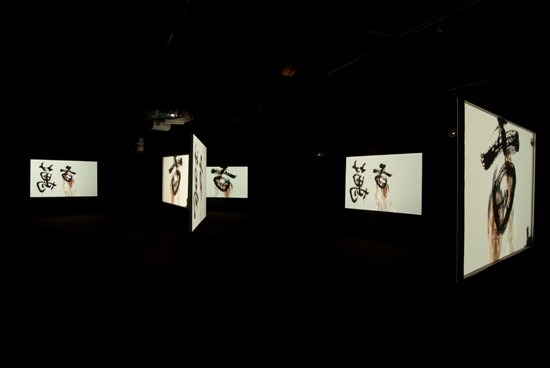

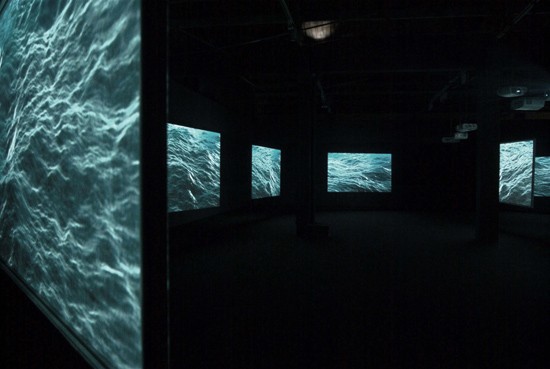

Installation view of TEN THOUSAND WAVES (2010) at ShanghArt Gallery, Shanghai, 2010. Nine-screen installation, 35mm film transferred to High Definition, 9.2 surround sound, 49 min 41 sec. Photo Adrian Zhou, courtesy of Isaac Julien and ShanghArt Gallery, Shanghai.

‘Wang Xiu Yu’

I have no time

To make love to my wife

I have no time

To watch my son grow

I have no time

To feed my mother

Excerpted from Wang Ping’s “Small Boats” cycle for Ten Thousand Waves

ART iT: We were just discussing your insertion into Ten Thousand Waves of footage from a Hong Kong-produced documentary on the Morecambe Bay tragedy. That sequence was very poignant for me because it was so short, and there is a shift in texture from film to video, and the juxtaposition from the spectacular landscape to a present-day interior. It’s an insertion of realism into the work that disappears as quickly as it appears.

IJ: That’s right. Because in a way I’m dealing with the representation of the broader situation, not just the actuality, although I do make use of actual filmed events through the police footage and the documentary. I spoke with some Chinese scholars involved in cultural studies who are very interested in what’s happening in the independent-documentary movement in China at the moment, and they were saying that this is the most interesting development in cinema now. That attracts me but there’s probably a limit to what I could do with that approach. I’m involved in a certain aesthetics that is connected to translating ideas and politics in a way that is not connected to realism. My work is connected to a poetic rendition or meditation on politically charged questions through a recourse to the sublime.

ART iT: On the other hand you also have the specter of Orientalism where the representation is so removed from the source that it becomes an objectification, and not a dialogue. Was that a concern of yours?

IJ: Of course it was a concern but I don’t think my work has anything to do with the “specter of Orientalism.” My images are really connected to the fact that I chose a Fujianese legend. By evoking Mazu, a figure who is still worshiped today, I think I am able to converse with the historical legacy of how people from Fujian province have moved through space and time. Historically speaking the tragedy is but one among many, and I’m sure there are many fisherman that Mazu could not have rescued. That’s why at the end of the work I reveal the goddess on a green-screen stage set, deconstructing the myth so to speak. So I’m working on a meta-narrative level.

I utilize fantasy to make political statements where some might think a more politically realist strategy would be more appropriate. But for me, I see all images as being constructed, whether they’re documentary or fiction. They’re all fabricating a particular point of view, except one is a genre that we could call “documentary” and the other is more stylized in form. The fact that I want to pose certain political questions through a stylized lyrical formation is probably what’s unusual, a purposeful jarring on my part. My use of a bricolage of sources and of filmic textures along with elements of fantasy essentially takes my work into the realm of the hyperbolic, the realm of myth and legend.

Installation view of TEN THOUSAND WAVES (2010) at ShanghArt Gallery, Shanghai, 2010.

ART iT: Did you ever see Matthew Barney’s Drawing Restraint 9, which was shot in Japan and which drew heavily upon quintessentially “Japanese” imagery? Do you see any parallels between that film and your own?

IJ: What Matthew does is very interesting but I don’t think that I would naturally draw a comparison between our works. I see my project as being quite different. I think Mathew is from a long tradition of Western artists who are influenced by Asia, which of course I am too. The difference is that he is quite playful in the way that his aesthetics draw attention to these influences. For example he takes Björk, a pop star, and costumes her as an Asian. A project like Ten Thousand Waves has a different aesthetic approach to what Matthew is trying to achieve, and so needs a different reading. While Matthew takes a quite ironic line as his “spin” on the tradition, I like to think that the kind of pictures that I make with Ten Thousand Waves are more critically engaged. My “trespassing” has to be done in a much more canny or careful way than Matthew’s. That’s why I have worked with actresses like Zhao Tao or Maggie Cheung to create a more sincere dialogue.

It’s perhaps worth noting that an approach like Mathew’s always seems safer because Björk is a pop star. Within the codes of fashion and advertising, it tends to be more acceptable to comment on these kinds of transgression. I prefer to signify Chinese culture through more symbiotic collaborative working methods, although this more reparational approach naturally still entails a manipulation of certain aesthetic codes and genres.

ART iT: Do you have any hesitations when you make a work overseas about how far you can trespass, or is your goal to trespass as much as possible?

IJ: I’m using the word trespass provocatively but I think for myself it has to be nuanced, because the simple fact is that once you have a camera and you point it at something, you’re always going to be engaging in visual trespassing. So in a way I’m always dealing with the question of representations, even if it’s something that could be called “post-colonial representation.” The images are not “of me.” It’s really about the negotiation. What is the content? What are the politics at stake, what are the visual aesthetic conversations that are taking place across geographies?

We’re all involved in that but I think for some people it involves immense risk. The risk I take as an artist is absolutely nothing compared to people who illegally cross borders.

Thinking about the notion of stereotypes in relation to a work like Ten Thousand Waves, there are certain tropes I’m invoking to move beyond identification. I’m completely aware of what people are going to think when I’m shooting in a landscape like Guangxi, which has this Avatar feel to it. I know it’s got this kind of familiar Orientalist landscape because I’ve looked at the Mazu drawings in the British Museum, which are incredibly beautiful drawings. But I think it’s what you do with these representations that’s important. I could never just be interested in a formal aesthetic exchange across cultural boundaries.

Someone like Quentin Tarantino has pointed his camera at particular cultures, but in that case it’s a conversation in the space of entertainment; it’s fun, and we derive a “bad” jouissance from it. In an art context it becomes inscribed in another way that could be more problematic. I’m interested in a serious reframing of those concerns since, after all, it was a post-colonial critic, Edward Saïd, who wrote the book Orientalism.

When I’m involved in reconstructing the Mazu myth I want to maintain a certain integrity. That integrity is in my collaborations and in relation to the performances given by the actors. So there’s a lot of energy, precision and detail involved. When I’m working with the Chinese crew and Zhao Tao’s performing, I can’t understand what she’s saying, since I don’t speak Mandarin, but my cameraman will tell me, “Isaac, that’s a great take.” This is a shared concern.

I guess what I want to say is that artists, especially filmmakers, have always been involved in trespassing and translating cultures and working together and it’s in that position that I find a potential unison and dis-unison. I’m not interested in the Chinese culture for the sake of representing something on the basis of its aesthetic difference. Images for me have to be politically convincing to work.

Both: Installation view of TEN THOUSAND WAVES (2010) at ShanghArt Gallery, Shanghai, 2010.

ART iT: But you also have an interest in performance, collaborating with choreographers to find an abstract or non-narrative way to communicate ideas.

IJ: At the opening yesterday it was just as important to be able to see the audience in the space as it was to see the work, because the way the audience negotiates the screens is a kind of dance that interests me and it was really important in Shanghai to witness that.

I have also been working on a show called “Move: Choreographing You,” which will take place at the Hayward Gallery in London this October and will include Ten Thousand Waves. What I call parallel montage relates to the choreography of the gaze. There’s a question of performance in the work, but it also doesn’t end there, it’s also about the way in which the screens are articulated architecturally and how people are relating to them in the space. Some people come in and just sit down – maybe they’re tired. But let’s just say that when we’re looking at moving images we fall into certain habits, and I’m trying to break down those habits in a gallery context.

The question of performance is also interesting in the sense that there was never a script for Ten Thousand Waves, so in a way all of the takes were filmed rehearsals.

ART iT: Well, I assume the Wong Kar-Wai veterans you worked with like Maggie Cheung are already used to that improvisational approach.

IJ: Yes. Wong Kar-Wai probably doesn’t remember meeting me, but I remember meeting him. Ashes of Time (1994) is one of my favorite films. I think it’s his signature film in terms of how the choreography of the camerawork is constructed. It’s a work from before we know Wong Kar-Wai as the Wong Kar-Wai of today. In that sense I’m always interested in works in which people are working through certain aesthetic strategies, but not in a completely conscious fashion. In other words, there’s something that’s very authentic about Ashes because one of the other problems that can develop is that everything can become over-rehearsed. Then the styling gets a bit stagnant – it’s not fresh.

Nor can I deny that Maggie Cheung’s image in that movie is quite similar to her role of Mazu in Ten Thousand Waves. There are certainly quotations, and when you’re working with someone like Maggie she brings with her a whole cinematic, historical legacy that’s connected to her performance.

Installation view of TEN THOUSAND WAVES (2010) at ShanghArt Gallery, Shanghai, 2010.

ART iT: You talked about meta-narrative. Could you say that this is a film that’s set in China but about England, in the sense that immigration is a major political concern there?

IJ: Absolutely. In a way the problem with how immigration gets debated in England is that opponents pretend that there are people who are trying to come into the country when actually these people have already been there for a long time. This is where the post-colonial aspect is important because there is such an old relationship to the empire, and those debates just trivialize and mock that relationship. What makes London fantastic is the fact that it is so cosmopolitan that in some ways we forget our identities, we’re simply all Londoners. So if Ten Thousand Waves is about England as much as it is about China, it’s the fact that I, a black Londoner, made it and it will show at the Hayward in London and will be my aesthetic contribution to that debate.

Isaac Julien’s Ten Thousand Waves is on view in the Biennale of Sydney through August 1, and will make its London premiere in the exhibition “Move: Choreographing You,” on view at the Hayward Gallery from October 13, 2010, to January 9, 2011. An exhibition of photographic works related to Ten Thousand Waves will be on view at Victoria Miro Gallery, London, from October 7 to November 6.

All images: Photo Adrian Zhou, courtesy of Isaac Julien and ShanghArt Gallery, Shanghai.

Cover Image: Green Screen Goddess (Ten Thousand Waves) (2010), Endura Ultra photograph, 180 x 240 cm. Courtesy of Isaac Julien, ShanghArt Gallery, Shanghai, and Victoria Miro Gallery, London.