The Patience of Materials

By Andrew Maerkle and Natsuko Odate

Installation view of the exhibition “Perfect Moment” at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, 2011. Photo Keizo Kioku, courtesy Yutaka Sone and David Zwirner, New York.

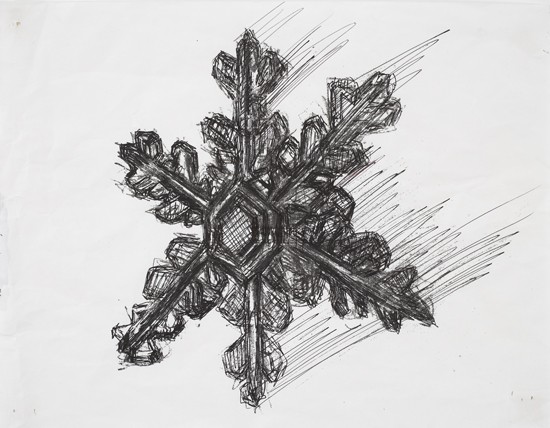

Yutaka Sone is best known for his marble sculptures of landscapes ranging from Hong Kong Island to imagined alpine scenes, as well as his “snow flake” works in crystal. However, employing materials that have taken milennia to come into being, and producing objects that seemingly uphold traditional ideals of eternal art, Sone embodies a contradiction in that he values above all else spontaneity and spends as much time generating ephemera such as notes and sketches as he does finished products.

Concurrent solo exhibitions in Tokyo at Maison Hermès and Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, respectively, are allowing Japanese viewers the chance to appreciate both bodies of marble and crystal work, as well as other aspects of Sone’s practice including paintings, drawings and early videos. ART iT met with Sone in December 2010 following the opening of his exhibition at Maison Hermès to learn more about how he views himself and his art.

We also include as an addendum to the interview a special text intervention that Sone performed for ART iT when presented with an advance list of questions.

Contents:

Part I: Yutaka Sone on his creative approach

Part II: Material/Film

Part III: Sculpting in Time

Addendum: Interview/Intervention

I. Yutaka Sone on his creative approach

Reference sketch for ART iT diagramming “gardening-style creativity,” December 2010.

ART iT: This issue of ART iT looks at the theme “Text” both in its literal sense and as a metaphor for the way that we read the world. Although your works do not use text per se, writing seems to be a big part of your practice, and you yourself have previously compared your activities to the development of a bildungsroman narrative. Can you explain more about this idea of the bildungsroman?

YS: In the past I had this idea of the bildungsroman and creating a specific setting for things to take place, with this image that each and every work was an inscription of the direction I wanted to follow. But I have since evolved and now approach every day as an improvisation, along the lines of musical improvisation. This spontaneity applies not only to storytelling, but also includes how I evaluate or read each moment, and the act of creation. It occurs when I do performances in front of people, and when I make works. From when I awake to when I sleep – and including when I am thinking – I am constantly moving, living.

ART iT: So although you started out with a narrative structure of the “beginning of a journey” and the “end of all journeys,” have you since abandoned that approach?

YS: I had originally planned for the end of all journeys to be chapter nine in my bildungsroman, but in the end I made it chapter three, because I was looking at the journey that happens after the end of the journey. This vague feeling that I had at the time actually connects with our current discussion, although now it’s not so much that the journey is the theme as it is that I am now in this situation where since I am already traveling, anything that I make necessarily becomes a part of the theme.

What I value most right now are the things that can only be said in this moment, or that can only be done in this moment, or that have to be done in this moment. I want to focus all my energy on that. I feel that sensibility emerges in my sculptures and drawings. There’s no distinction between “rehearsal” and “performance” for me; I’m always on stage.

Installation view of the exhibition “Snow” at Maison Hermès Le Forum, Tokyo, 2010. Courtesy Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, © Nacása & Partners Inc.

Installation view of the exhibition “Snow” at Maison Hermès Le Forum, Tokyo, 2010. Courtesy Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, © Nacása & Partners Inc.ART iT: Does that mean everything you do is in a somewhat unfinished state?

YS: I wouldn’t put it in terms like “unfinished” or “unbuilt.” Simply, I am “always making.” Putting it another way, I think of what I do as a kind of “gardening-style” creativity.

If I sketch it out, in my garden there is a patch for projects that take 10 years to complete, another patch for those that take three years, another for those that take one year, another for those that take three months, another for those that take three weeks, another for those that take one hour. You have all these patches for different projects with different needs that require different lengths of time, and then off to the side you have my home.

I wake at 4am and start work by 4:15. Over the course of the day I cycle through each project, and then I’m back home and in bed by 8pm. I don’t even know which project will be completed next. Some projects mature quicker than others. Just as a gardener spends time with each of his plants every day, I also work on a sculpture, and then a drawing, and proceed from one project to the next based on intuition.

ART iT: So would you say that you don’t really think of yourself as an artist?

YS: I really don’t – except for when I’m introduced as an artist in a social situation, and then I have this sudden realization that that’s what I am. Normally I am completely alone in my studio – just me and the birds and the cats and the dog. I can go for months by myself just thinking and making. The first thing I do in the morning, from 4:15 to around 6am, is to draw sketches for planned projects, thinking through different approaches for how to begin. I don’t really have time to think about what it means to be an artist. But if I go to a museum or into the city, then maybe I put on my artist act. Everybody has their own profession, and acts out what they think that should be.

ART iT: In this sense would you say that your works also embody the multiple levels of time that reflect your “gardening” practice?

YS: It’s definitely apparent. When I work on a long-term project all kinds of emotions accumulate. In the case of short-term, momentary works, if I feel a sudden rush of happiness I might paint everything blue, and produce something that looks expressive. Then the next day when I’m a little more relaxed and admiring the work, I might add a few more touches to it. In this way over time all kinds of moods end up being recorded in and layered onto the works. In conceptual terms, too, they include different layers of contrasts and contradictions.

Installation view of the exhibition “Perfect Moment” at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery,2011. Photo Keizo Kioku, courtesy Yutaka Sone and David Zwirner, New York.

Installation view of the exhibition “Perfect Moment” at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery,2011. Photo Keizo Kioku, courtesy Yutaka Sone and David Zwirner, New York.ART iT: Does this relationship with time relate directly to the materials you use, such as marble or crystal?

YS: It’s both a matter of choice and of destiny. In addition to Los Angeles I have studios in China and Mexico, and at each studio I carry out different projects using different materials. In China it’s stone carving. In Mexico it’s rattan weaving, making large-scale models of tropical trees that we finish with painted details. The colors we choose for the paint reflect the intensity of the sun in Mexico because I feel that the light there has this reddish tint that spills everywhere and makes everything look yellow.

It took me about 10 years to fully appreciate weaving. One of my collectors is the owner of a ceramic studio in Mexico, and he kept inviting me to make a project using his facilities. I don’t like ceramic, maybe because once you have a mold you can make multiple versions of the same work – the same goes for prints. But because I wanted to make trees, I looked into the possibility of rattan weaving and realized this was the technique I wanted to try.

So to answer your question sometimes when I have an idea I know immediately what kind of material to use, and other times when I don’t know what material to use I am unable to act on an idea. If I try to make a work using the wrong material then it just ends up looking forced; I prefer to wait until I’m certain. I’ll even wait 10 years – five years pass very quickly for me.

ART iT: That kind of temporal friction I find is part of the appeal of your works.

YS: Yes, although it does not take so much time for me to actually produce a work – I am a fast draftsman and a fast carver. However, considering the speed of the art world one concern with production is that you can easily get overwhelmed. I try to set my own pace. That is “gardening.” If I’m nurturing an idea and it still hasn’t fully matured, then I leave it alone until it’s ready.

In the case of my marble sculptures, I love more than anything else the moment when I carve into the material. When I carve away one centimeter, three centimeters, five centimeters, 10 centimeters – the millennia and eons over which that stone came into being become visible in the form that I give it. Then the time represented by the work’s subject matter, the time distilled by the stone and my own personal time in that space all begin to overlap in a way that is almost meditative. I don’t know if it’s appropriate to say it this way or not but time becomes sexy for me, this kind of meditation. It’s orgasmic. When I am carving it is extremely fun.

Yutaka Sone: The Patience of Materials