III. Sculpting in Time

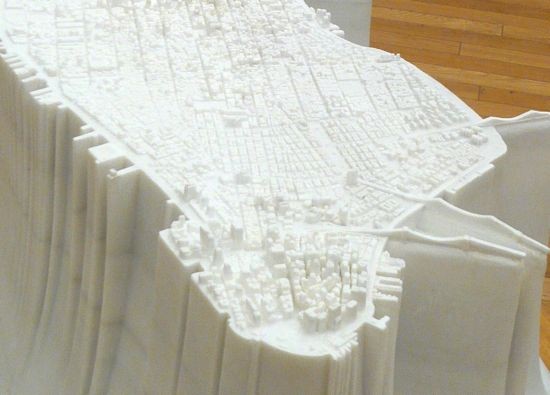

Left: Yutaka Sone, photo Grant Delin. Right: Photo of Little Manhattan (2010) under production at Yutaka Sone Studio, Chongwu. All images: Unless otherwise noted courtesy Yutaka Sone and David Zwirner, New York.

ART iT: You just said that being a beginner at guitar is in a way preferable to being a master, because you can take more pleasure in minor, daily improvements in your ability. When you’re carving stone, do you still feel anything similar to the sense of development that you receive from guitar practice?

YS: For sure. I am by far the best stone carver in the town of Chongwu in Fujian province, where my China studio is located. I do the parts that the best craftsman is ultimately unable to do, or sometimes we work together – and the best craftsman is a young guy who started 10 years ago and has never worked on anything but my projects.

The last time I was in Chongwu we were in a race against time. There is a 48-year-old guy who is another top carver but he was taking too long with his assignment. This guy is a veteran but it was his first project with me so he didn’t fully understand the concept or the carving style. I grabbed the tools and started showing him how it’s done, but after another two weeks had passed I realized there was no way we could meet the deadline, so I called over the younger guy and the three of us started carving together, one crafstman on each side, me working underneath. The idea for the work was to have two trees with a space for light going between them, and working on the bottom was the toughest part. I couldn’t see the model so I had to keep a photograph with me to reference, but with the other two carving away on top, flakes of marble dust were swirling around me like a blizzard.

ART iT: Was it fun?

YS: You bet it was! I work harder than anybody else so nobody has any complaints and there’s no internal politics. Everybody willingly gives me their best. The craftsmen joke that I do the work that they won’t do. We have a lot of fun together. The work itself is our entertainment. Usually the craftsmen won’t let anyone touch their tools but I’ve been there 10 years already and they know I’m the best.

ART iT: The story about the boy who has never worked on anything but your projects is particularly impressive as an illustration of the scale of your art practice.

YS: Actually, I instructed him not to work on anything else. I don’t want him to pick up bad habits working on high-volume commercial projects, so for that reason alone I have to keep coming up with ideas for him to carry out. In Chongwu the workshop chief is 55-years-old and I am 46-years-old, with workers around our age considered veterans – only by that point our eyes have started going bad and our mouths are pretty filthy too, even though we’re the directors. The young guy is really good. The problem is that he is proud and doesn’t like working with other people. That’s something he has to overcome, which is why I wanted to bring in another veteran, and then in the end we ran out of time, and finally had to rotate the three of us working nonstop for a week.

Left: Photo of Light Between the Trees #2 (2010) under production at Yutaka Sone Studio, Chongwu. Top right and bottom: Installation view of the exhibition “Snow” at Maison Hermès Le Forum, Tokyo, 2010-11. Photo ART iT.

ART iT: Is it pretty intense in the workshop?

YS: When we work we have to be calm; nothing good comes from rushing. Even if we look intense the energy level is very flat, tranquil. When I talk about not meeting a deadline, it’s not like we only have three days left to complete something. We have to assess how things will shape up a month or even several months before the deadline, and then adjust strategy if it looks like we’re running behind.

For the current Hermes show here in Tokyo we have nine new crystal sculptures on display, and the thing is that beyond simply carving the sculptures there’s also the problem of polishing them. Too much polishing at once raises the surface temperature of the material and then the sculpture cracks. We have to go as slow as possible. By May 2010 we could tell that we weren’t going to meet the deadline, so around June we restructured the team in order to have everything ready for the December opening.

There are certainly times when the workshop does look wild though, like when we bring in the raw stone. We’re talking about a chunk of marble that weighs seven tons, really heavy. There’s no way to move that stone by hand, we need a forklift. But the forklift we use has a maximum capacity of six tons, so if we put a seven-ton stone on it, the back end is up in the air, and because it’s a rear steering vehicle there’s no way it can move. Then one by one the craftsmen in the workshop try climbing onto the back end to see if their combined weight can even it out, and they’re all gung-ho about it, striking poses and shouting encouragements to each other. But even that has no effect. In the end we have to borrow another forklift and use two vehicles in tandem, like ants carrying a leaf.

And then with a seven-ton stone, the first thing we have to do is clean it. Cutting away the gray parts gets the stone down to about three tons, and after we work on it the final piece is about 1.7 tons. So with a five-to-seven-ton raw stone there’s about three tons’ worth of pure white material to work with. It’s like a chef working with a fish.

ART iT: You have previously stated that you dislike the idea of collaboration as practiced in an architecture studio, but how is that any different from when you are at your workshop in Chongwu?

YS: In the case of architecture you are making a plan, but not physically involved in the construction, which is why it didn’t suit me. Obviously the scale of architecture is so large that there is no other way to go about it. In my case with the workers, we’re arguing with each other and operating on a more practical, simple level – “That’s wrong!” “Do it over!” “No good!” It’s very direct.

I myself am a simple and primitive person. I don’t watch TV, I don’t use the Internet. I have an expensive phone that I carry around because I like the way it looks. I like accessories. I have these pockets in my bag, and I want to buy things to stick in them – that makes me happy. But I don’t really use anything. When I bought an iPod I got the version with the maximum memory, thinking that were I to fill it with data I could take it everywhere and it would be convenient for meetings with curators, but after testing it out I ended up not using it, and don’t even have it with me. I have no idea how to work it. I’m a failure with computers. I admire people who can use them, but for me it’s tools that feel natural.

Detail of Little Manhattan as installed at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, 2010-11. Photo ART iT.

ART iT: You also apparently write poetry. Are you still writing? What kind of approach do you take to your writing?

YS: I am always writing. Sometimes poems, sometimes anecdotes. It’s all handwritten. A lot of it is pretty trivial. I’ll write down anything that happens to pass through my mind, and then it becomes poetry. For example, if I’m thinking about the things I have to do tomorrow and want to clarify those things that seem incoherent, then I’ll even turn that into a poem. I use English, Japanese, Chinese – sometimes I even have to share them with my workers.

ART iT: So your memos become poems and your poems become memos?

YS: I am constantly writing, although this Hermes exhibition is the first time I have ever published my essays [produced in a pamphlet freely available to exhibition visitors]. I rarely do interviews. When I was living in Japan I would refuse every request. People would advise me to take a more accommodating attitude, but because I was not very socialized I didn’t have any sense of what it meant to be accommodating, and then that would lead to trouble. I generally tried to avoid the public.

But I’ve mellowed with age and gradually come to think that I should try to explain my concepts better, so this time I decided to write those two essays and asked Hermes to publish them. Even 10 years ago whenever I finished an exhibition I would get on the plane the next day. If you spend too much time in these rarefied environments you get carried away thinking that you’re some kind of great artist, and it affects your next project. I always return home straight away and get back into my workaday routine as soon as possible.

You know, when they enjoy too much praise artists go bad. I think we need to make a sign, along the lines of “Don’t feed the animals.”

ART iT: If you’ve mellowed with age then do you feel that the fruits in your garden are now ripe?

YS: Well, it’s important to deliver the things that are ripe while they are still fresh and then return to the garden as soon as possible to take care of the next crop.

Work by Yutaka Sone is on view in Tokyo concurrently at Maison Hermès Le Forum in the solo exhibition “Snow” through February 28, and at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery in the solo exhibition “Perfect Moment” through March 27.

Previous:

Part I: Yutaka Sone on his creative approach

Part II: II. Material/Film

Yutaka Sone: The Patience of Materials