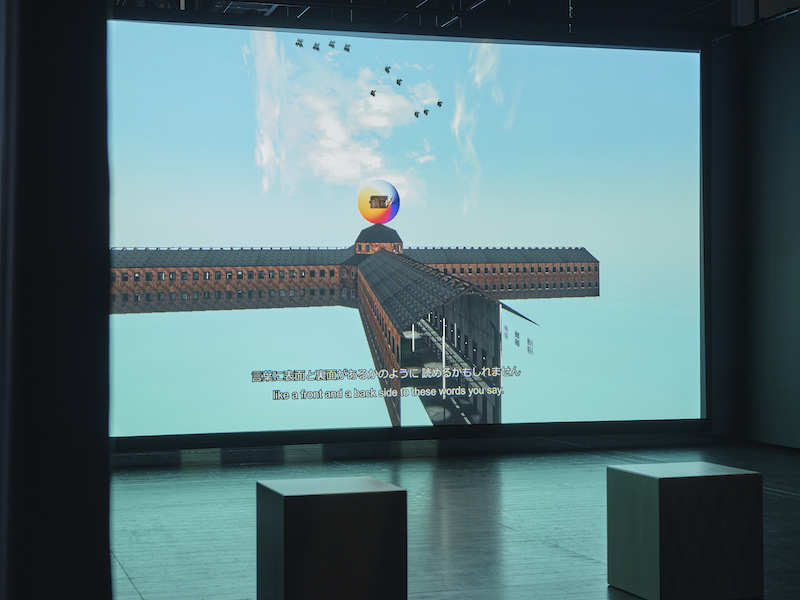

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Review: Voice of Void by Ho Tzu Nyen

Jung-Yeon Ma (film and new media studies)

Translation: Tomoyuki Arai

“Why the Kyoto School Now?”

Ho Tzu Nyen’s solo exhibition “Voice of Void” was presented at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM] from April 3 to July 4, 2021. At the beginning of the talk with the artist and the production team held at the opening of the exhibition, the question was posed: “Why the Kyoto School now?” The Kyoto School is said to be a group of philosophers representing the history of modern thought in Japan formed around Kitaro Nishida (1870–1945) and Hajime Tanabe (1885–1962) at the Department of Philosophy, Faculty of Letters, Kyoto Imperial University in the Taisho and Showa periods. The definition of the term involves diverse points of view, but in general, it is used to refer to a genealogy of thinkers who were taught by Nishida and Tanabe and developed their activities influencing each other(1).

Having created and presented the new work through collaboration with YCAM for some two years including the postponement of the exhibition due to the pandemic, Ho explained “why the Kyoto School now” citing the following reasons. Firstly, his interest as an “Asian” in their philosophical attempts to overcome and reconstruct modern Western philosophy and technicist worldview. Secondly, the skeptical reaction of his Japanese friends, most of whom must have been cultural workers and art people, to the idea of working on the Kyoto School. The more negative their reaction was, the stronger Ho’s conviction about the subject matter became. This remark must be an important clue to understand the artist’s approach to history. Moreover, the most important reason that he mentioned was today’s world. He thought that reflecting on the history of the Kyoto School, who strove for a single solution in the middle of the convoluted situation of the world war and thus failed, would be an intellectual exercise in articulating the complexities and contradictions of a world that does not comprise a single answer.

Ho had been interested in the Kyoto School for several years before working on this piece. For example, his previous work Hotel Aporia (2019), presented at the Aichi Triennale 2019, also refers to the Kyoto School’s collaboration with the Japanese military during World War II. Rather than dismissing this historical fact with the existing judgement as “war cooperation by intellectuals,” he continued his investigation into this matter over a long period of time, of which results are reflected in the latest work. In an interview with Andrew Markle at the time, Ho said, “They say the road to hell is paved with good intentions. This mixture of racism and utopian thinking, this interweaving of good and bad is part of what interested me with the Kyoto School. […] In some sense, I think I am probably much more interested in the Kyoto School as a historical phenomenon than I might be in the philosophy they produced.”(2)

What is the “Kyoto School as a historical phenomenon”? The commentary by the “voices” in the work, which I am going to quote many times, on the roundtable discussion at the center of Voice of Void will provide a clue. The roundtable discussion, “The Standpoint of World History and Japan,” “attempted to define Japan’s mission in the unfolding of world history, one that can no longer be defined solely from the perspective of the West. It was an attempt by Japan to philosophically overcome the West, just as Japan was attempting to overcome the West in the battlefields.” If the dichotomy of “Japan” versus “the West” is the assumption, the question that we asked at the beginning is likely to implicitly encompass another question about who the subject is: “Why you?” If that is the case, the questions cannot be resolved simply by the word “Asian.” As a non-Japanese Asian just like Ho, I was interested in his “viewpoint” because it is the viewpoint of someone who is neither “Japanese” nor “Western,” someone who does not have a rightful place in the choice between “Japan” and “the West,” and someone who has been excluded from both “Japan” and “the West.”(3) As suggested by such works as Utama: Every Name in History is I (2003), The Nameless (2015), The Name (2015), and The 49th Hexagram (2020), Ho has been deeply interested in the “subject of history” that is not confined to a single framework.(4)

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Zabuton Cushions and Sheets of Paper—Place of History and Act of Recording

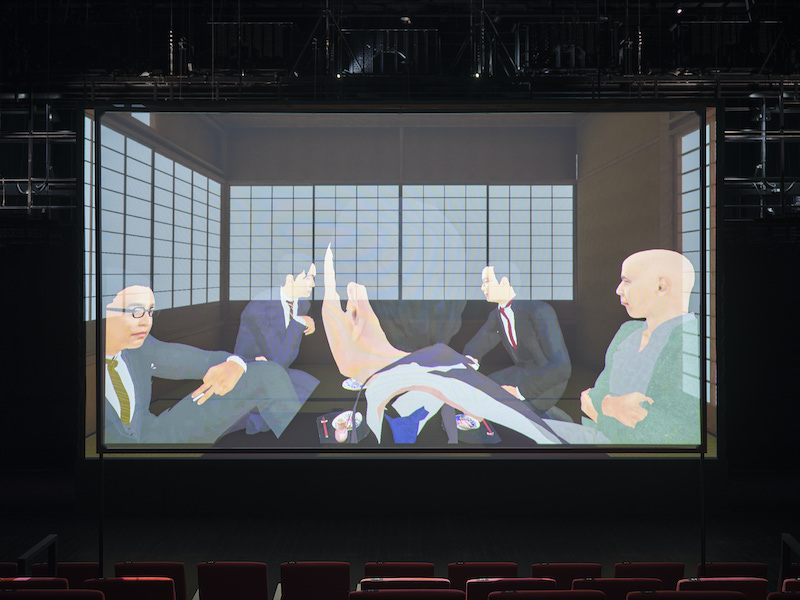

As I walk into the exhibition hall through a corridor lined with full-body sculptures of the philosophers Masaaki Kosaka (1900–1969), Keiji Nishitani (1900–1990), Iwao Koyama (1905–1993), and the historian Shigetaka Suzuki (1907–1988), all of whom had been transformed into 3DCG animation characters, I hear young male voices whispering in the darkness. As I proceed without understanding what the voices are telling, I see the red audience seats on the left, illuminated by the reflection of two screens. Conscious of the fact that there are more screens on the far right, the visitor sits in the seats and watches the projections in front of her, and before she knows it, she has taken on the role of a spectator in a movie theater.

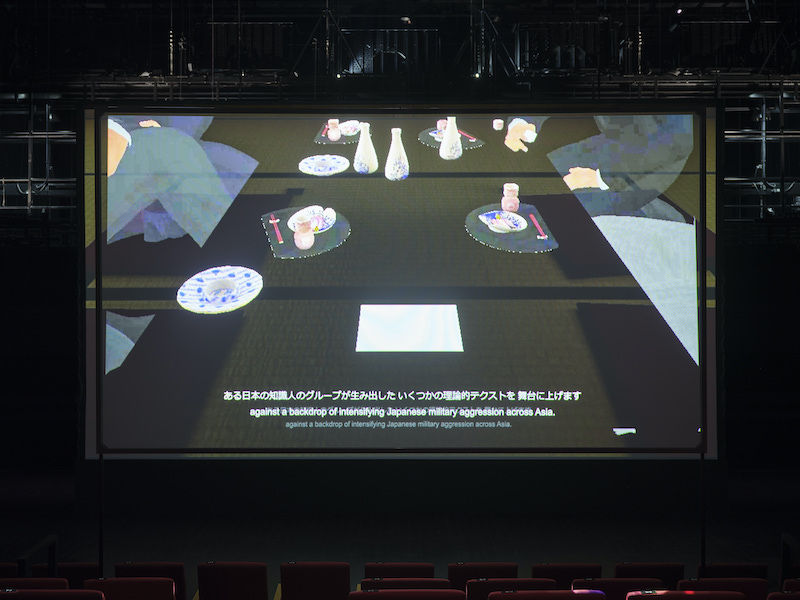

However, the “voices” say something enigmatic to the audience: “Thank you for agreeing to lend your voices to this project…” The audience is usually supposed to be silent in a movie theater or museum. What does it mean to lend our voice? The one who is speaking through the many “voices” from the multiple screens that echo throughout the space refers to himself as “I.” The “voices” whisper quickly, as if they are afraid of something, as if they are pressed for time: “…where we attempt to stage a number of theoretical texts produced by a group of Japanese intellectuals during the 1930s and 1940s, against a backdrop of intensifying Japanese military aggression across Asia. The text that you will voice…” This mystery of “lending one’s voice” and “voicing the text” further raises the audience’s expectations for the subsequent development of the work.

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

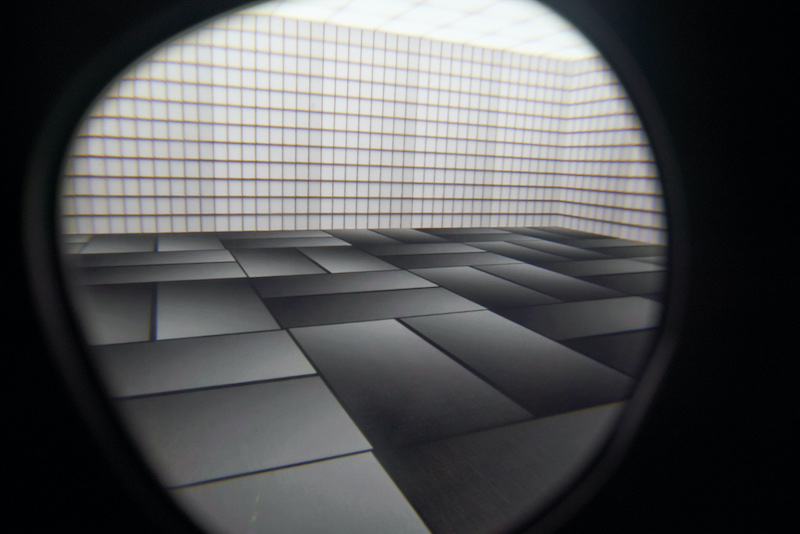

There are two screens in front of the audience seats. The characters are projected on the translucent screen in the foreground, and the space behind the characters is projected on the other screen in the background, which are combined by the audience’s eyes to form a single image. It is interesting to note the self-reflexivity between content and form: the screening of animation involves a spatial materialization of the production method, in which characters and background are separately drawn and then layered. Furthermore, the animation depicting Kosaka, Nishitani, Koyama, and Suzuki discussing in a tea-ceremony room, instead of immersing the audience in a true-to-life depiction, exposes the fact that they are merely graphics through the camerawork that passes inside the hollow of the figures. According to the description by the “voice,” the scene depicted is a roundtable titled “The Standpoint of World History and Japan” held in a tearoom of a Kyoto restaurant Saami in 1941 at the request of the magazine Chuo Koron (The Central Review).(5) Only 12 days later, the attack on Pearl Harbor began, and the war situation turned fully into World War II. The fact that the Malayan Campaign that started the same day led to the occupation of Singapore on February 15, 1942 suggests that the discourse of these Japanese scholars, who were banned from public office after the war for their ideological support of military action, is not totally unconnected to the artist Ho himself.

What confuses the audience, who has acquired the cinematic convention of watching events unfold on a single screen, is that while the two screens are displaying different layers of visual information, one of the characters and the other of the background, the “voices” from the two screens that are initially synchronized occasionally diverge, and then synchronize and diverge again. It seemed to me that the “voices” were synchronized when two conditions were met: one is when “historical facts” are discussed, such as the definition of the Kyoto School or the outbreak of the war, and the other is when events that took place at different times share the same “place,” the tearoom of Saami. Especially when “historical facts” were being told, it seemed that not only the “voices” from the screens in front of me but also those assigned to other screens in the back were synchronized. It was as if they were unanimous that at least these specifics can be accepted as “well-known facts.”(6)

Naturally, it is the conditions of the divergence that we should pay attention to. Firstly, two screens diverge into the stories of the master and of the disciples. Behind the foreground screen that depicts the four characters, the background screen that provides the backdrop goes back to the past before the roundtable and explains Nishida’s philosophy as the premise of the Kyoto School’s thought, Nishida’s 1938 lecture at Kyoto Imperial University entitled “The Problem of Japanese Culture,” and secret meetings between the Navy and the Kyoto School with the aim of countering the Army led by Hideki Tojo that started in 1939. The synchronization and divergence of the two screens make the “pseudo-experience of place through virtual reality” in the latter half of the exhibition and the core concept of Nishida’s philosophy, “the place of absolute nothingness,” resonate in a curious way.

Ho Tzue Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzue Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzue Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzue Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

From there, the points of view of the two screens move further and further back. Outside the tearoom is a round colored ball floating like a planet in the 3D space. Technically, this is just an intentional exposure of the default tool of the program that implements the background of the CG image, but it highlights the spatial and theoretical unreality of the discussion on war that takes place in the tearoom, which is far away from the battlefield. Above and below it, the sky and the prison are connected on a vertical line, respectively. This is the moment when the structure of the VR world that visitors are about to experience is presented in advance.

Here, the “voices” from the front and rear screens begin to talk about different people respectively. The screen in the background, shifting from the secret meetings during the war to the future after the war, talks about the ethicist Yasumasa Oshima (1917–1989), who recorded Tanabe’s lectures and the secret meetings as his assistant. Defending the Kyoto School’s attempt as “criticism of the system within the system,” Oshima testifies that there were army and right-wing threats against the Kyoto School in the background.(7) On the other hand, the screen in the foreground shows Masuzo Ohya (1901–1977), a stenographer belonging to the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper company, who was supposed to be sitting on the fifth cushion in the tearoom, recording the discussion on blank sheets of paper on the table. The “voice,” referring to the fact that Ohya had witnessed Japanese military atrocities in China three years before the roundtable, says, “It is impossible to tell how he felt recording these roundtables.” Then, the “voice” quotes from a portion of his tanka poem collection, Asian Sands (1971), which was published under a name with the same pronunciation Masuzo Ohya with different Chinese characters 30 years after the roundtable: “There used to be such words as absolute nothingness and I wonder what words those scholars have now.”(8)

The camerawork of the scenes that focus on the recorders, Oshima and Ohya, who are not so well known to the public, encourages the audience to think about “distance.” For example, while inside the tearoom, it is impossible to grasp the whole picture of the world. On the other hand, while we have a bird’s eye view of the whole, we can obtain information about what precedes and what follows, but we are separated from the event in specific time and space that is placed at the center of the work. This mechanism is similar to the relationship between audiovisual information and space that we experience on a daily basis, so it can be understood intuitively. Through the gradation of various perspectives that exist between subjectivity and objectivity, the artist questions the “distance” that conditions our understanding of history.

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

The Physicality of the Audience

After two projections of prison scenes on the two sides of a screen and another two projections of sky scenes on two screens facing each other, the audience reaches the space for the VR experience. Four zabuton cushions are laid out on black tatami mats, and up to four people at a time are invited to wear head-mounted displays (HMDs) to watch the work.

As with other computer-related technologies, VR is deeply tied to the lineage of research and development for military purposes. It experienced a brief boom in the 1990s when devices for consumer use began to be sold.(9) In the run-up to the new millennium, the collapse of the former Soviet Union and communist bloc, as well as the proliferation of the Internet, raised social expectations for “another world.” Despite the technical limitations of the time when it could not yet be fully implemented, or perhaps because of the very gap between the experience and reality, it had an impact not only on science and technology, but also on art and thought.

VR is one of the scientific, philosophical, and technological frontiers of our era. It is a means for creating comprehensive illusions that you’re in a different place, perhaps a fantastical, alien environment, perhaps with a body that is far from human. And yet it’s also the farthest-reaching apparatus for researching what a human being is in the terms of cognition and perception.(10)

Jaron Lanier, a scientist, engineer, musician, and writer who founded the first VR research and development company, VPL Research, in 1984, added another definition to the above: “the medium that can put you in someone else’s shoes; hopefully a path to increased empathy.”(11) Certainly, compared to the end of the last century, when futuristic works were the mainstream, in recent years, the second wave of VR has seen many works that question the (im)possibility of empathy for others by approaching the physical senses of the viewer on a more mundane level. As an example, we can take up Jordan Wolfson’s Real Violence (2017), which caused a stir by forcing the audience to witness the artist beating a person to death with a baseball bat on the street.

As a former master’s student at a computer vision laboratory of the faculty of engineering, I have a mild aversion to HMD devices. This is due to the real inconvenience that we have to accept in order to experience, literally, virtual reality, as well as the antipathy towards the act of entrusting ourselves to a machine. It may just be a matter of “getting used to it,” but I personally cannot shake the impression that the weight of the device and the oppressive feeling caused by the restricted field of vision, the ridiculousness felt when we see people immersed in the audiovisual information presented by the device, and the embarrassment felt by the viewers themselves remain unresolved. It is precisely because these flaws are inseparable from the senses that it is necessary to pay attention to how Voice of Void designs the “physicality of the audience” in the VR experience. It is said that Ho, who had no choice but to collaborate with YCAM in the form of telepresence due to the immigration restrictions imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic, was adamant in his discussions with the Japanese technical team to eliminate cables and controllers from the VR equipment. “I think that was because he wanted to ensure the audience’s active participation as much as possible in the expression of their involvement in history,” said YCAM InterLab’s Richi Owaki, who oversaw the technical direction of the piece.(12) In other words, the artist must have prioritized the physical freedom of the audience over technical stability.

What was simply surprising for me was the length of the experience, which is exceptional for a work using VR, which can involve side effects ranging from eye fatigue to dizziness and vomiting.(13) The playback time of the scenes seen through the HMD is said to be about 2 hours and 30 minutes for the tearoom alone, and more than 3 hours if the prison, sky, and zazen room are included. Furthermore, some of the scenes continue to play ambient sounds even after the reading is over, which means that the duration of the VR experience is, in principle, unlimited. The scene of the tearoom is long because the full transcript of the roundtable discussion “The Standpoint of World History and Japan” is used without editing. Moreover, the events in the tearoom unfold in linear time that cannot be “fast-forwarded” or “rewound,” just like a feature film seen in a movie theater. In the context of contemporary art, where the decision of how long to see a work of art is left to the individual viewer, the length of time itself may not be much of an issue. However, the fact that the trigger for the “playback” of the scenes is the viewer’s physical movement is a crucial difference from ordinary video works, and the same fact connects the work to the game. What kind of game-like rules is this experience connected to?

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

When you sit down on a tatami mat and start the experience, you are shown the scenery of the tearoom that you have just seen on one of the screens. From the angle of view and the sheets of paper on the table in front of you, you know that you are sitting in the position of the stenographer recording the four scholars’ roundtable. VR viewers often subconsciously look down at their hands. Those who did that would have seen their virtual hands and a pencil and realized that this was some sort of role-playing game setting. If you act out the role of the stenographer and make hand movements as if you were writing something, you will hear the roundtable discussion in front of you.

The discussion, at the early stage, is led by Kosaka and Suzuki, and this is what they had to say.

KOSAKA In other words, what is Japan’s mission in world history? When we confront these questions, we have no reason to expect answers from Western thinkers. Japanese people have to find the answers ourselves. It is these kinds of questions for which the philosophy of world history has become a particular quest for contemporary Japan. […] The ways of thinking are changing significantly. Philosophy as a discipline has become a method of establishing where one finds oneself in this historical flux while also suggesting in which direction one should move in. […] rather, it inches forward as a form of study that provides direction to what historically changes. Philosophy orientates us. […] I do not know of many other countries where the philosophy of world history is being taken as seriously as it is in Japan.(14)

While the conversation is developing rapidly, the four figures are just repeating small movements, so the audience’s attention is naturally focused on listening to the voices and writing with their hands rather than looking. When they stop moving their hands, tired from listening to the voices and repeating the same movements, they hear a soliloquy that seems to echo in their heads. This is Ohya’s own voice, which cannot be heard while he is concentrating on his work as a stenographer, and what is muttered are some of the tanka poems included in the aforementioned Asian Sands. Ohya’s tanka poems, which were made 30 years after the roundtable although both belong to the past for the 2021 audience, lament about the tragedies of war that he has witnessed and about his own inability to do anything about it. The artist’s stance remains unchanged here: “It is impossible to tell how he felt recording these roundtables,” where young scholars with no battlefield experience discuss the “direction” of war. On the other hand, the audience, playing Ohya’s role, can never ignore their own subjectivity that has been established in the same situation as Ohya’s when listening to the roundtable.

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

As the viewer lowers his or her posture, the sight slowly sinks vertically, and soon the gloomy prison landscape unfolds in front of them. When the viewer reaches the ground, it moves horizontally and switches to the point of view of a person lying in a dirty cell with wriggling maggots. In the prison scene, the audience encounters Kiyoshi Miki (1897–1945) and Jun Tosaka (1900–1945), who were imprisoned for their relationship with communists and died in prison of malnutrition and nephritis caused by scabies, and their writings. One is Miki’s “The World Historical Significance of the China Incident” (1938), a transcript of his talk delivered at the Showa Research Institute, which was reviewed by Miki himself. This institute was the private political study group of Fumimaro Konoe, who became prime minister in 1937, just after the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, then called the China Incident, and Miki’s speech became the basis for the study group’s concept of “East Asia Cooperative Community.”(15) The eloquence of his speech that the audience hears, arguing, “The unification of the East, therefore, is a world historical agenda delegated to the Japanese race,”(16) contrasts cruelly with the image of the emaciated man in prison. Miki’s expectation that World War II would be a way to overcome the conflicts between liberalism, fascism, and communism and to create “the philosophy that could unify the world,” as well as his argument that the significance of the China Incident was about “unifying the East” spatially and “resolving the capitalist society” temporally,(17) can be said to be ironies of life and history where the future cannot be foreseen.

When the viewer raises their body and stands up, they ascend vertically through the tearoom into the sky. Floating in the blue sky is a squadron of mecha reminiscent of the Zaku, the most unexceptional, mass-produced “mobile suit” (manned humanoid robot weapon) in the Japanese anime series Mobile Suit Gundam. The viewer takes the point of view of the pilot of one of the mecha. Heard from above, as if from the voice of God, is a reading from a public lecture titled “Death-Life” that Tanabe gave at Kyoto Imperial University. I couldn’t help but feel angry at this lecture, in which Tanabe explains attitudes toward life and death by classifying them into an attitude where one sees death as a natural phenomenon, an attitude where one actively thinks of death as an issue and gains awareness of their own existence, and a practical attitude where one actually dies. My anger comes from the fact that this lecture was given on May 19, 1943, when the war situation was intensifying, and its main audience were liberal arts students who were about to go to war after the draft deferment was lifted. I do not agree at all with Tanabe, who glorifies “determination to die” as rebirth, resurrection, and true freedom for young men who are forced to face the danger of death, and who says, “man touches God, and connects to God, through sacrificing himself to the state.”(18) However, the upset I experienced was not only due to anger at Tanabe’s unforgivable words and actions as a professor and scholar. The squadron of mecha, which is at the same time a reference to Japanimation and a representation of lethal weapons, gradually dissolved and disappeared leaving only the blue sky and white clouds. The upset was also due to a state I remained as a consciousness without the mecha body in the space. This separation of body and consciousness closely resembled the split between my head that aggressively resisted Tanabe’s voice and my heart that could not help but find tragic beauty in the images that metaphorically depicted the deaths of suicide attackers.

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

From Voice to Text, and Back to Voice Again

Sight isolates, sound incorporates. […] sound pours into the hearer. […] When I hear, however, I gather sound simultaneously from every direction at once: I am at the center of my auditory world, which envelops me, establishing me at a kind of core of sensation and existence.(19)

In his book Orality and Literacy (1982/2002), Walter J. Ong wrote that the act of writing a text moves the words, originally spoken as a voice, from the auditory to the visual world and reconfigures them in the visual space, thereby transforming both speech and thought, and finally, they become definitively rooted in space by printing.(20) Using VR, “the ultimate media technology, meaning that it is perpetually premature,”(21) Voice of Void unearths the words rooted in the written space of historical records, reconstructs another world of voices, and invites the audience to enter it.

I was curious to know why Ho included the entire text without any editing in spite of the fact that it is not an easy task to go through the entire work in a venue with a limited VR viewer capacity, so I decided to get a copy of the out-of-print compilation The Standpoint of World History and Japan from a secondhand bookstore and read it. As Ong pointed out, the words in print were read as something completely different in quality from when heard as voices, and my reading was interrupted again and again by the feeling that something was choking me.

There is no doubt that this book is an important document. There are countless places where we can feel intellectual stimulation: Koyama’s view that there are two modernities in Japan, the pre-Meiji Restoration modernity and the post-Meiji Restoration modernity, which are “in a discontinuous continuity,”(22) Nishitani’s idea that “there are discontinuities within the continuities, and continuities within discontinuities,”(23) the scene where all four of them criticize Western modern technological worldview for having an excessive faith in technology,(24) or the following scene where they discuss the problem of philosophy and reality metaphorically.

KOSAKA This is quite strange, but I gave my relatives something of a shock during my school years, when I announced my intention to study philosophy. They were terribly worried that I might commit suicide by jumping into the Kegon Waterfall. […] I actually saw philosophy as something remote from real life.

[…]

NISHITANI But at the same time, I think that philosophy can also embrace a Kegon-like aspect, I mean, an aspect of the Kegon Waterfall.

SUZUKI What? Kegon what?

NISHITANI I mean Kegon-like. Not the Kegon sutras. Mine is more like the Kegon Waterfall.

[All laugh]

KOSAKA That’s right. Without something like that, philosophy will never be authentic. It will fall short of true seriousness.

KOYAMA Hmm, like the Kegon Waterfall. It should be a Kegon Waterfall where the way by which the individual and the absolute are connected is filled with the historical world. Pour world history into the Kegon Waterfall and leap from the highest rock of the Japanese spirit into the water.(25)

However, there are also parts that I personally find very violent such as their justification of armed war as the dynamics of moral energy, referring to the German historian Ranke’s concept of the driving force of history, and their discriminatory remarks that they make when discussing the nation and state as the subject of that force.

KOYAMA When one talks of war, one immediately assumes that war is unethical and that ethics and war are never connected. To think in this way is to reduce ethics to something simply formalistic. […] there is a moral energy to be found in war. […] I think the triumph of Germany means that the German race had the moral energy to win. […] The fall of a nation is in fact a result of the exhaustion of the people’s moral energy.(26)

Exactly as the “voice” said at the beginning of the exhibition, “I imagine the four to be excited by their own ideas and how they might be received,” the roundtable gets more and more heated as it proceeds.

KOSAKA But currently, our ground covers the huge expanse of geography that forms the whole of East Asia, stretching from China to the southern islands. There lies the ground for manifesting real moral energy. […] In this sense, Japan is required by world history to seek such principles. I feel that Japan is being urged from behind, as it were bearing the world-historical necessity.

[…]

KOYAMA It is true that the significance and ideal of these incidents emerge only afterwards. I think this is always true of history. Significance in reality is created as the incident proceeds. It is our actions that create the significance in reality. The potential of the China Incident is for us to enliven or spoil through the choice of our future actions.(28)

The roundtable is concluded with Kosaka’s following words in response to Koyama’s remark: “History stands on the frontier between heaven and hell.”

KOSAKA As Professor Nishida observed recently, world history is the purgatory of the soul of humankind. It’s the realm of purgation. […] When human beings are indignant, the indignation is felt in their whole bodies. Indignation is felt in both mind and body. It is the same with war. Indignation is manifested in both heaven and earth. And this is how the soul of humankind purifies itself. This is why war has determined significant turning points in world history. And it is this that makes world history a purgatory.(29)

I wonder how the readers of this review receive these words that I read feeling indignation in my whole body. The fact that the roundtable asset runs in linear time means that the audience can never hear these words directly unless continuing the VR experience for more than two hours. Furthermore, given the practical condition that the book is out of print, the number of viewers who looked into the “darkness” at the depth of the work must have been small. The “voice” in the 2D projection I saw at the beginning quoted some of this closing remark, but that still had a different resonance from the remark that came out of the verbal exchange between the four speakers.

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

This work hides another time-space that the VR viewer can enter by not moving at all. It is a zen meditation room where one can hear excerpts from Nishida’s 1938 public lecture “The Problem of Japanese Culture.” It is not easy, because the scenery of the zazen room disappears in an instant if you make even the slightest movement, but if you control your breath, adjust your posture, and concentrate on not moving, the gray geometric space expands infinitely. Listening to an elderly man’s voice reciting a series of sentences that all end with “must be,” I even felt as if I am receiving some kind of guidance from him. The sentences were too difficult to understand just by listening to them, but interestingly, it was possible to find different meanings in them by detaching myself from the original context and connecting to the worldview in this VR experience and the work as a whole.

The world of absolutely contradictory self-identity must be the world where the past has not passed yet while it has already passed, the future has already been present while it has not come yet, and the present encloses the past and future, the world where time as the unification of the opposed is perpetually spatial, and conversely, the world where space as the place of force is perpetually temporal.(30)

Nishida’s lecture is the most difficult of all the materials used in the work, but it is said that when it was published as a book in 1940, it sold over 40,000 copies. From this fact, we can infer the authority and influence of the Kyoto School in Japanese society at that time. In the first projection, the “voice” mentions that Nishida died on June 7, 1945, just before the end of the war, and goes on to say, “I imagine that Nishida’s voice, detached from his fleshly body, emanating from behind the scenes, permeating what his various disciples do.” This reminds of the fact that in this work, Nishida and Tanabe are not visualized as 3DCG characters, i.e., they do not have physical bodies, but exist as “words=voices.” Not only such fragments as “The state is not merely moral oughtness but must be moral energy as Ranke puts it,”(31) ideas that are shared among the master and disciples are found in many places in the work. Nishida’s rhetoric and concepts are like an abyss that swallows up all contradictions. That makes it possible, for example, while he cautions against altering the Imperial Way into military rule and imperialism, to preach, “We must contribute to the world by finding at the base of our historical development the principle of the self-formation of the very world of contradictory self-identity. That must be to demonstrate the Imperial Way, and that must be the true meaning of hakko ichiu [the unification of all eight corners of the world under one roof].”(32) The same thought is inherited in Nishitani’s discourse perfectly.

The task that confronts our country today is, needless to say, the establishment of a new world order and the construction of Greater East Asia. It is for the realization of this task that we now need the total mobilization of national power, and especially, intense moral energy. However, the construction of Greater East Asia must not mean the acquisition of colonies for Japan, of course, and the establishment of a new world order means nothing but the establishment of a just order. In a sense, this is a world-historical necessity, but at the same time, the necessity has been undertaken by Japan as its own mission.(33)

The book The Standpoint of World History and Japan includes a “preface” written by the four roundtable speakers in their joint names on February 1, 1943, before publication, in which they disclosed that there was no predetermined subject at the time of the discussion on November 26, 1942, that the war broke out when they were about to finish proofreading the transcript of the discussion to be published in the January issue of Chuo Koron, and that the title “The Standpoint of World History and Japan” was given “after” the discussion. “We watched, with inexpressible emotion and determination, how our thoughts were judged by the solemn world-historical reality.”(34) They went on to mention two other criticisms they were receiving at the time. In response to the criticism that their position lacked Japanese subjectivity, they explained, “We just tried to expound theoretically that Japanese subjectivity must not be self-righteous or dogmatic,” and, “What we call world-historical necessity is not mere natural necessity, obviously, but a subjective necessity that while developing through the awareness and practice of the Japanese subject, bears the significance of world historical oughtness.” In response to criticism that they were overly beautifying Japan’s reality, they responded as follows. “We believe that the truth of Japan is unfolding distinctly through the Greater East Asia War right now and are firmly convinced that the practice of the truth will correct the injustice in reality.”(35) Paradoxically, the reason why they “strove for a single solution and thus failed” must have been that they never questioned this conviction.(36)

What is noteworthy is the fact that they published their discussion almost unchanged, knowing the limitations of the format: “Of course, as the format of a roundtable discussion shows, this is nothing but the tentative, discursive product of the immaturity of our thinking at the time.”(37) I have to say that this was a courageous decision on the part of the scholars, since scholars understand better than anyone else what it means to have words remain in written form. Likewise, it must have taken “courage” for Ho, curator Kazuhiko Yoshizaki, and everyone else involved in the production of this exhibition to summon the words of these scholars, which became the basis for criticism of the Kyoto School after the war, to the present day in their original form. In fact, there was an audience member who asked the artist about the ethics of having someone play a figure that historically existed. After pointing out that their statements were public, Ho mentioned the “respect” that he always kept in mind in the process of breathing life into their words through the channel of himself. Tomoyuki Arai, who dramaturged this work, expounded that the reason why they asked theatre people to offer their voices was that they are more aware than anyone else of the ethical issues of putting ideological messages directly into the ears of the audience.(38)

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Individual Imagination of History

In the end, Ho’s viewpoint suggested by the “voices” was not a single interpretation of history, but one that gently whispers, as if staying with us, to encourage us to reflect on “distance”; one that bets on the “imagination of history” of each individual. When I say this, some readers may be disappointed, thinking that “imagination” is a cliché of contemporary art. However, it took a lot of “courage” for me to come up with this word because, personally, thinking about this work was an experience of unlearning that was not without pain. It was a process of confronting the historical education in my country that I must have subconsciously internalized, of consciously putting it aside for a moment to look at the imperialism of a neighboring country that colonized my country and to listen carefully to the words of the individual intellectuals who supported the imperialism with conviction, and then of thinking again for oneself. For example, the process would begin with reading Tanabe’s “Death-Life,” which had emotionally upset me when I listened to, and finding with surprise that the text is not inflammatory but rather calm and logical, even though it was the exact same words.(39) Then I would have to “imagine” the position of the male students, who must have been in dire need of the meaning of their impending deaths, and the position of Tanabe, who attempted to give them some kind of philosophical answer. Then I would have to go one step further and “imagine” that for Tanabe it might have been his “repentance.”

Hajime Tanabe lecturing on death-life to students going to war I saw the oppressive authority of academism

Lectured on death and sent students to war who said it was philosophy that bleeds

I also hear he kept silent after his farewell speech to students going to war Hajime Tanabe with sickness onto death

Was it the destined direction of the study that was defeated together with the country both the study and person

Now I regret my stenographs of Hajime Tanabe that was archived by the university and cannot be found

Spending the day when thought arises and flows about the sadness that Japanese language bears

Masuzo Ohya, “Lecturing on Death-Life”(40)

The final text in the VR that I mention, which we hear in the prison lying down as Miki did, is Tosaka’s Reflection on Pacifism. It was written in 1937, the year when the China Incident began. While the other texts in the work were printed versions of spoken words, such as a roundtable, university lectures and political discourse, which were presented to the audience to be “read=heard” again, only this text was written from the beginning in order to be “read=seen,” with many blank spaces that visually suggest censorship.

Temporary wars or incidents in the East can be considered an inevitable necessity for establishing perpetual peace in the East. […] Logic that is externally applicable does not necessarily apply internally. The state as a category embodies an absolute value beyond logic to that extent. Therefore, the China Incident is, in its entirety, no more than the manifestation of Japan’s external perpetual pacifism and is exactly an external flipside of internal social pacifism. International justice as opposed to social justice is precisely that. Japan has a Japanist cultural theory, which argues quite a bit about domestic social justice, but quite surprisingly, we hear no collective voice by penmen on international social justice in regard to the China Incident. needs to educate penmen a little more on this issue. […] I mean we are Japanese and no other nationality or race. For us, the subject is Japan. Opposite to that is the object. As long as we know the distinction between the subject and the object, we should be able to reach a clear understanding that the China Incident is a phenomenon of peace. […] It means that this Japanese logic called pacifism can apply internationally, as long as nothing but is there. In short, Japanese logic requires for the purposes of objective application of itself. Then, one can understand for the first time why pacifism must turn to battle and —peace is necessary for oneself.(41)

Was Tosaka really thinking as he wrote? That may be so. But to me, it looks like a dysphemistic text that plays on self-censorship. Perhaps that is the limit of my viewpoint. The fact that it was published in Jiyu (Freedom),(42) a magazine founded with the goal of overthrowing the control of speech, is not enough to support my impression, but I think at least, as the “voice” comments, the text can be read “as though it was designed with a kind of double-sidedness, like a front and a back side to these words.” I think so because, when the text is read as an antithesis and paradox, it can be interpreted as an appeal that the Japanese logic, which is not capable of considering the issue of peace from the standpoint of the object=other,(43)] i.e., different nations and peoples, cannot be accepted internationally, and that peace for oneself alone is not peace. What Tosaka expects from the reader and Ho expects from the audience may be that each will fill in the “void” with their imagination—the “void” in the discourse of the Kyoto School that I came into contact with through this work was precisely imagination toward others.

According to the talk with the artist and production team that was streamed online on the first day of the exhibition, a major turning point in the production process was Ho’s question, “By the way, who was recording this roundtable discussion?”(44) If it did not cast a light on the recorder of history, Masuzo Ohya, his existence and his viewpoint, Voice of Void would have been a completely different work. It was impressive that the dramaturg Arai described Ohya as the “conscience” of the work. When I asked him about the expression “conscience” a few months later, Arai chuckled a little and said that he might have a tendency to seek such correctness.(45) It was an answer that sounded somewhat like the voice of Ohya in the tanka poems.

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen, Voice of Void (2021) Photo: Ichiro Mishima, Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

*1 Kyoto School Archive, https://www.kyoto-gakuha.org/about/thekyotoschool.php._

*2 “Ho Tzu Nyen: Leap Beyond Void (2),” https://www.art-it.asia/en/top_e/admin_ed_feature_e/212110._

*3 Naoki Sakai, “Jo: Pax Americana no moto deno Kyoto gakuha no tetsugaku (Introduction: The Kyoto School Philosophy under the Pax Americana),” Hara Takahashi (trans.), in Naoki Sakai, Jyun’iti Isomae (eds.), “Kindai no chokoku” to Kyoto gakuha: kindaisei, teikoku, huhensei (“Overcoming Modernity” and the Kyoto School: Modernity, Empire and Universality), Ibunsha, 2010, p. 4. Sakai elaborates more on the question of the non-Japanese, non-Western viewpoint in the Japanese, “translated” version of the text than in the “original” in Naoki Sakai, “Resistance to Conclusion: The Kyoto School Philosophy under the Pax Americana,” in Christopher Goto-Jones (ed.), Re-Politicising the Kyoto School as Philosophy, Routledge, 2008, p. 183._

*4 These works were screened at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media on June 26 and 27 in “Selected Video Works of Ho Tzu Nyen,” a related event to the exhibition “Voice of Void.”_

*5 After this, two additional roundtables, “Toa kyoeiken no rinrisei to rekishisei (The Ethical and Historical Character of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere)” and “Soryokusen no tetsugaku (The Philosophy of Total War),” with the same speakers were held in the following year, 1942. The full text of the first roundtable that was held before the war began in full scale is used in this work. The three roundtables by the four scholars were published in March 1943 as a book entitled Sekaishi teki tachiba to Nippon (The Standpoint of World History and Japan), but the book was not reprinted due to opposition from some of their family members and is now out of print._

*6 In fact, the projections on the six screens—the tearoom, sky, and jail scenes, each of which occupies two screens—are of the same length, 7 minutes and 45 seconds._

*7 Oshima argued that the postwar ideological movements for peace and democracy, such as the campaigns against atomic and hydrogen bombs, were “criticism of the system from outside the system,” while what the Kyoto School did was “criticism of the system from within the system.” He argued that the two were the same in their commitment to politics and war issues, although he admits that they resulted in the opposite due to the difference in the situations Japan was placed in. Yasumasa Oshima, “Daitoa senso to Kyoto gakuha: chishikijin no senso sanka ni tsuite (The Greater East Asia War and the Kyoto School: On the Political Participation of Intellectuals,” in Tetsuro Mori (ed.), Kyoto tetsugaku sensho 11: Kitaro Nishida, Keiji Nishitani, hoka, “sekaishi no riron” (Kyoto Philosophy Collection 11: Kitaro Nishida, Keiji Nishitani, et al., “Theory of World History”), Toeisha, 2000, pp. 274–304. First published in Chuo Koron, August 1965._

*8 From Masuzo Ohya, “Uzu no shozai (The Whereabouts of the Vortex),” in Ajia no suna (Asian Sands), Sorobanya Shoten, 1971, p. 93._

*9 There is also a view that the origin of the artistic application of VR can be traced back to Wagner’s essays on Gesamtkunstwerk (1849); see Randal Packer, Ken Jordan (eds.), Multimedia: From Wagner to Virtual Reality, W W Norton & Co Inc, 2001._

*10 Jaron Lanier, Dawn of the New Everything: A Journey Through Virtual Reality, The Bodley Head, 2017, p. 1._

*11 Ibid., Appendix 1, p. 299._

*12 Hearing on June 26, 2021. In 2018, Owaki, as an artist, presented a VR installation The Other in You in collaboration with YCAM._

*13 The duration of the aforementioned Real Violence is 2 minutes and 25 seconds._

*14 Masaaki Kosaka, Keiji Nishitani, Iwao Koyama, Shigetaka Suzuki, Sekaishi teki tachiba to Nippon (The Standpoint of World History and Japan), Chuo Koron-sha, 1943, pp. 4–7. Also, “The Standpoint of World History and Japan,” in David Williams, The Philosophy of Japanese Wartime Resistance: A reading, with commentary, of the complete texts of the Kyoto School discussions of “The Standpoint of World History and Japan”, Routledge, 2014, pp. 110–113. The book includes his translation of the roundtable, and I refer to the corresponding pages in the book for the reader’s convenience, but the quotes in this review are from another English text that Ho used. It was put together by his Japanese dramaturges, Tomoyuki Arai and Miho Tsujii, thoroughly revising Williams’ translation under the supervision of Harumi Osaki. For Ho’s view on the book, see https://www.art-it.asia/en/top_e/admin_ed_feature_e/211811._

*15 According to Jun Sugawara, Miki’s discussions on Asia, including “The World Historical Significance of the China Incident,” came to be known as an “East Asian Cooperative Community” theory when political scientist Masamichi Royama, who had been a key member of the Showa Research Institute since its inception, published his “Toa kyodotai no riron (Theory of East Asian Cooperative Community)” in a magazine Kaizo in response to the Second Statement by Konoe on the war, also known as “East Asia New Order Statement.” Jun Sugawara, Kyoto gakuha (The Kyoto School), Kodansha, 2018, pp. 112–113._

*16 Kiyoshi Miki, “The World Historical Significance of the China Incident,” in Critical Space, Vol. 2, No. 19, Ota Publishing, 1998, p. 36._

*17 Ibid., pp. 34, 36._

*18 Hajime Tanabe, “Shisei (Death-Life),” in Tanabe Hajime Zenshu (The Complete Works of Hajime Tanabe), Vol. 8, Chikuma Shobo, 1964, p. 260._

*19 Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the World, Routledge, 2012 (first published in 1982 by Methuen & Co., Ltd.), p. 71._

*20 Ibid., pp. 84, 121._

*21 Lanier, Dawn of the New Everything, p. 204._

*22 Kosaka, Nishitani, Koyama, Suzuki, Sekaishi teki tachiba to Nippon, pp. 26, 29; Williams, The Philosophy of Japanese Wartime Resistance, pp. 123, 125._

*23 Ibid., p. 61; Williams, p. 143._

*24 Ibid., pp. 40–41; Williams, pp. 130–133._

*25 Ibid., pp. 93–96; Williams, pp. 162–163._

*26 Ibid., pp. 102, 104; Williams, pp. 167, 168._

*27 Ibid., pp. 125–126; Williams, p. 178._

*28 Ibid., pp. 127–128; Williams, p. 179._

*29 Ibid., pp. 130–131; Williams, p. 181._

*30 Kitaro Nishida, Nihon bunka no mondai (The Problem of Japanese Culture), Iwanami Shoten, 1940, p. 55. _

*31 Ibid., p. 131._

*32 Ibid., p. 82._

*33 Keiji Nishitani, “‘Kindai no chokoku’ shiron (A Personal View on ‘Overcoming Modernity’),” in Tetsutaro Kawakami, Yoshimi Takeuchi, et al., Kindai no chokoku (Overcoming Modernity), Fuzanbo, 1979, p. 32. Nishitani is the only one in the four roundtable speakers who returned to Kyoto University after being expelled from public office._

*34 Kosaka, Nishitani, Koyama, Suzuki, Sekaishi teki tachiba to Nippon, p. 2. Williams did not translate the preface of the book._

*35 Ibid., p. 6._

*36 The fact that the Kyoto School cooperated with the Navy in opposing the Army-led war against the United States does not change the fact that they supported the “Greater East Asia War” itself. See Akira Asada’s remarks in his conversation with Ho Tzu Nyen (Aichi Triennale, October 13, 2019). “There are some people who argue that the Kyoto School was close to the navy and tried to defend the minimum necessity of liberalism in opposition to the explicit totalitarianism and imperialism of the army. That makes some sense, but eventually the navy was equally bad as the army, and the Kyoto School was too.” (https://icakyoto.art/en/realkyoto/talks/82897/)_

*37 Kosaka, Nishitani, Koyama, Suzuki, Sekaishi teki tachiba to Nippon, p. 4._

*38 Talk session on June 27, 2021. They played Nishida, Tanabe, Miki, Tosaka, and Ohya. Kosaka, Nishitani, Koyama, and Suzuki were played by professional voice actors._

*39 “Death-Life” was not written down by Tanabe himself. It is a record of his speech, and two versions have been published. One was recorded by a student for the Kyoto Teikoku Daigaku Shimbun (Kyoto Imperial University Newspaper) and confirmed by Oshima, the assistant of Tanabe. The other was recorded by Oshima himself, asked by Tanabe before the lecture began. Yasumasa Oshima, “Commentary,” in Tanabe Hajime Zenshu, Vol. 8, pp. 472–473. The version used in this work is the latter, for which Oshima was responsible._

*40 Ohya, Ajia no suna, pp. 102–103._

*41 Jun Tosaka, Reflection on Pacifism, in Jiyu (Freedom), Vol. 1, No. 10, October 1937, Jiyu-sha, pp. 30, 32–33. These blank spaces are replaced in the VR experience by electronic sounds typically used to censor voices._

*42 The following is a quote from the post-editorial note of the magazine, which was a “wartime special edition.” “In August and September, we continued to incur displeasure of the authorities and were ordered to delete some articles. First of all, we apologize to the readers for the inconvenience. We do not dare to resist the authorities. We think we are not that childish. However, it is our original duty to look at the changes of the times with a critical eye and try to come to a correct conclusion. We are not trying to make an unfair profit by selling books. Isn’t today the time for journalism to carry out its essential task with this intention? Newspapers are one thing. Magazines are another, and so on.” Ibid., p. 176._

*43 In this text, Tosaka uses the words “shu” (subject, host, master) and “kyaku” (object, guest)._

*44 Talk by the artist and production team on April 3, 2021._

*45 Talk session with the artist and dramaturg on June 27, 2021._

Jung-Yeon Ma

Born in 1980, Seoul. Ma graduated from Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts with her doctoral dissertation on social implications of art and media technologies, which was later published as A Critical History of Media Art in Japan, (Artes Publishing, 2014). Her recent publications include Seiko Mikami: A Critical Reader (NTT Publishing, 2019: co-editor), “Exhibition Spaces Emitting Light and Sound: Contemporary Art and Image Media” (2019), “Art and Media” (2021), Paik-Abe Correspondence (Nam June Paik Art Center, 2018: co-translator) and Koki Tanaka: Reflective Notes [Recent Writings] (Art Sonje Center + Bijutsu Shuppansha, 2020: co-translator). She is currently working as associate professor at the Department of Film and Media Studies, Kansai University.

In Cooperation with:Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Ho Tzu Nyen: Voice of Void

3 APR – 4 JUL, 2021

Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM], Studio A

https://www.ycam.jp/en/events/2021/voice-of-void/

Curator: Kazuhiko Yoshizaki (Curator, Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media)