Art to help us live through these times

Mine Oka and Shunzo Sato (Part 2)

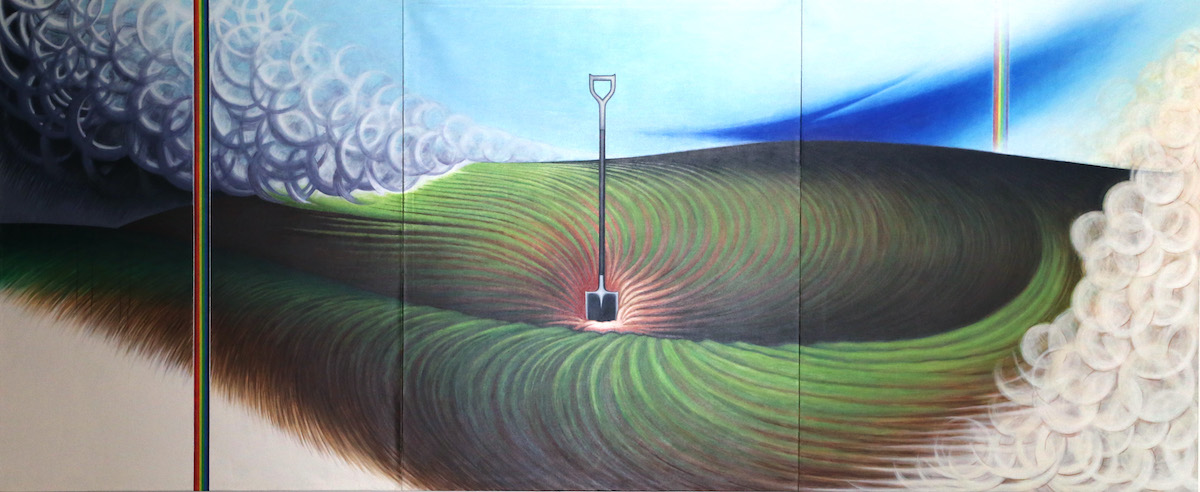

Shunzo Sato – Wako Dojin (Mingling with the world hiding the light of one’s wisdom and virtue), 2002.

Shunzo Sato – Wako Dojin (Mingling with the world hiding the light of one’s wisdom and virtue), 2002.

All photos: Mami Fukuzoe, courtesy Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum (except where otherwise noted).

As touched on at the end of my previous column, the two exhibitions that make up “Rainbow, Summer Grass, Softshell Turtle: Shunzo Sato” take the forms of “diffusion” and “condensation,” the former titled “One Place/Piece” (November 1, 2020 – January 20, 2021), and the latter “All About Shunzo Sato” (March 17-30, 2021). I use the terms “diffusion” and “condensation” because “One Place/Piece” presents individual paintings by Sato in various locations around Oita prefecture, while “All About Shunzo Sato” condenses the presentation into a single exhibition at Oita Art Plaza. Sato liked to use shapes and color combinations that call to mind the botany of plants. On that note one could say that the very plan of the two poles of this exhibition has the same kind of dynamic movement of the texture (or “temperature”) of living things – in that the single piece shows resembling spectacular fireworks suddenly exploding and sending petals in all directions eventually form fragrant fruits that are handed on to the next generation.

The exhibition came about after Keiichi Ninomiya and Hidekazu Kimura, who were close to Sato, decided on the tenth anniversary of Sato’s death at the age of 56 in 2010 that they wanted more people to know that such an artist existed. But irrespective of the strength of such a feeling, if no artworks survived it would not come to fruition. Luckily, there existed a small, privately run museum dedicated to Sato’s work called the Hananoki Museum.

This museum is located in Oga, Oita prefecture, where the Kunisaki Peninsula attaches to the mainland not far from Beppu, where the earth’s “body temperature” radiates in the form of terrestrial heat. As mentioned last time, the museum’s name derives from Hananoki Toride (Fort Hananoki), the name Sato gave to the studio he built in the wooded hills of Oga (Hananoki is also the name of the subsection of the village in which the studio was located). It was opened in 2012 by Sato’s older brother Shozo Sato and his wife, Sumiyo, who were determined to do all they could to ensure the public could continue to view the paintings Sato left behind. For more on the history of the museum and on Sato the man as well as his philosophy, I recommend Hananoki no kaze: Sato Shunzo hyoden (The Hananoki Wind: A Critical Biography of Shunzo Sato, 2017), which Shozo published at his own expense and to which my own criticism owes a great deal. In this sense, if “One Place/Piece” is the “flower” and “All About Shunzo Sato” the “fruit,” then the Hananoki Museum is like a “root” in the earth.

Exterior view of the Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum. Photo/courtesy Yuji Shinomiya.

Interior view of the Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum (13th exhibition). Photo/courtesy the Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum.

The Hananoki Museum attracts several hundred visitors annually, the majority of whom are repeat visitors. While some of these visitors are devotees who stop by every time changes are made to the exhibits, “now and then there are people who come from afar as if guided by the wind.” (Hananoki no kaze, p 65) Regarding this latter group, Shozo writes, “It may be that such people will never visit the museum again. This makes their single visit all the more precious. And makes me want to greet them as if it were a once-in-a lifetime experience.” (Ibid)

Just where do these people who arrive “as if guided by the wind” hear about the Museum, and what makes them want to see Sato’s paintings? No doubt the answers to these questions vary. The situation is different to large museums in urban areas that issue coordinated, large-scale publicity. It is not information. In fact it is more like the wind. Just as the direction, strength and feel of the wind change by the moment depending on the season, weather and temperature on any particular day, each visitor who heads for the Hananoki Museum has their own feeling and temperature, and probably senses something in Sato’s paintings without really knowing themselves what exactly it is. Which is no doubt why Shozo called his critical biography em>Hananoki no kaze (The Hananoki Wind). Near the end of the book Shozo writes, “It might be best to yield to the wind that blows across the plain. Regardless of the color of that wind.” (p 64) But precisely because each meeting is a once-in-a-lifetime experience, the wind that blows has various colors. Even if one decides to yield to it, one needs to make the corresponding preparations.

Despite changes to the exhibits being made only once every six months, this comes around surprisingly quickly. The selection of the works is mostly done by Sumiyo. She starts by making a list before discussing it with me. Both of us are amateurs, so we have no idea whatsoever if the combination of works is appropriate. We chose them based on our sensibilities. This is the most distressing time for us. It’s fine when works go well together, but sometimes a work is at odds with its neighbor. They resist each other. Sometimes one work alone sticks out. We’d probably ignore it if it were for a day or two, but even the works themselves would probably find it unbearable for six months, so when this happens we try choosing another work. Surprisingly, through a process of trial and error, we usually end up with an exhibit we feel satisfied with. But I can’t believe this is something we can achieve on our own. At times it’s as if we can hear a voice somewhere saying, “That’s not right; this is the way to do it.”

Hananoki no kaze: Sato Shunzo hyoden (The Hananoki Wind: A Critical Biography of Shunzo Sato), pp 62-63.

Such daily efforts gave rise to a kind of atmospheric pressure between the paintings, and between the people who visit the museum, and gradually a wind began to stir. And before anyone realized it this wind reached people surprisingly far away and spurred them into action. And it is because this very wind reached me that I am writing this column. What sparked this was the diffusion and condensation surrounding “All About Shunzo Sato,” and the place where this back-and-forth movement reminiscent of the cycle of life began was the “root” (or to take a cue from Sato’s paintings, perhaps we should call it a “bulb”) that is the Hananoki Museum.

And so it is that root turns into flower that eventually bears fruit before reverting again to root. “One Place/Piece,” “All About Shunzo Sato” and the Hananoki Museum are in such a back-and-forth relationship, and the thing connecting them is the colorful wind and the temperature that connects people. Unfortunately I was unable to view “One Place/Piece,” but I am certain this atmosphere also pervaded “All About Shunzo Sato.”

Installation view of “Rainbow, Summer Grass, Softshell Turtle: Shunzo Sato” at Oita Art Plaza, 2021. Photo Yuji Shinomiya, courtesy the Shunzo Sato Exhibition Executive Committee. The exhibition website features a virtual walkthrough of the exhibition.

Installation view of “Rainbow, Summer Grass, Softshell Turtle: Shunzo Sato” at Oita Art Plaza, 2021. Photo Yuji Shinomiya, courtesy the Shunzo Sato Exhibition Executive Committee. The exhibition website features a virtual walkthrough of the exhibition.

“All About Shunzo Sato” is not a retrospective. It undoubtedly features Sato’s paintings, but while it might be an exaggeration to say that they are imbued with the places they passed through and the people that viewed them as they were disseminated from their roots, when these paintings with different histories are arranged together, they do not appear homogeneous. So this is not a retrospective tracing Sato’s practice chronologically, but a comprehensive exhibition offering a panoramic view of his practice. This is clear from the way the works were displayed extensively throughout the large hall on the second floor of the venue like a single installation that provided an experience akin to wandering through a forest.

Even so, I was surprised at the diversity of the journeys the individual paintings had undertaken before arriving at such an exhibition. Looking at the exhibition map, I see these locations are so diverse and widespread it is almost dizzying. They include not only galleries but temples and companies, coffee shops and schools, train stations, government offices, libraries, stores of all kinds and cafeterias. To arrange them alongside each other like this is easy, but each has its own different look and is endowed with its own different temperature, and the individuals who run each place have their own way of living, meaning Sato’s works were no doubt received in various ways. That such an initiative as this was nevertheless possible was undoubtedly because the wind that began to stir from Fort Hananoki and passed Hananoki Museum reliably reached the various people concerned and moved them in some way. According to the text on the exhibition flyer, it was “an exhibition in which the works make their way out into the community.”

“Shunzo Sato: One Place/Piece” map. Photo courtesy the Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum.

However, the circumstances are different from an exhibition that tours art museums or galleries. No two locations offered the same conditions. Moreover, one thing led to another, and before long the number of venues, which was originally estimated to be 30, had grown to more than 100. Though there was an executive committee, most of the work was done by the above-mentioned pair, making for a shortage of hands. One can hardly imagine how difficult it must have been to install the works. However, the two men who came up with this idea of diffusion and condensation speak about it in a surprisingly cheerful manner.

Kimura: Upon installing them in the venues (the works took on new meaning by being placed there), the first place I felt this being Futago-ji temple. It was raining that day, the wind blowing furiously, but as I installed the painting amid the rustling and swaying of the surrounding forest, everything calmed.

Ninomiya: The owners of the Myojo ramen shop in Kunimimachi-Taketazu cleared the tokonoma in their tatami room and the painting fit there perfectly. But what really made me happy was when the president of the Hotel Seikai in Beppu said I could put the painting anywhere, meaning I could install it in the perfect place.

Kimura: One place that was refreshing was Mamenomonya in Ota, Kitsuki. Places like Uemura Bread in Usuki and Mametake Coffee deep in the Yabakei Valley you’d think weren’t really suitable, but they get quite a lot of customers. I was really impressed by the actions of the young people there.From a conversation published in the “Rainbow, Summer Grass, Softshell Turtle: Shunzo Sato” flyer.

Be that as it may, given that even after his death he transmits diffusion and condensation from person to person like rippling waves, exactly what kind of artist was Shunzo Sato? What follows is a brief overview.

Shunzo Sato was born in 1954 in Oga, Hiji, Hayami district, Oita prefecture, the same place where his self-built studio, Fort Hananoki, and the Hananoki Museum were later constructed. As a member of the drama club while studying at nearby Kitsuki High School, Sato was in charge of writing the script and directing a production of Kafka’s Metamorphosis, and this along with his involvement in the publication of a small literary magazine give an indication of his sensitive disposition towards the arts. He came from a farming family, but the facts that his father, Kitaru, who took over the family farm, frequented Kimuraya (a salon-like art supply store for the culturati) in Oita city from before the war and that his older brother Shozo, who wrote the above-mentioned critical biography, was also involved in publishing small magazines since his student days, suggest that Sato was destined to love art and literature from a young age. Endowed with such a passion for art, Sato built a studio in the place where he was born while helping out at the local agricultural corporation, continuing to produce paintings there until his death in the same place. In this sense, he lived much of his life with the temperature of the land.

Shunzo Sato – Water, three states: (left to right) Jozen (The highest goodness), 2008; Fuchi (A deep pool), 2001; Honryu (Torrent), 2002.

However, this does not mean he never left the place of his birth. After graduating from high school in 1972 Sato went to Tokyo, where apparently he aspired to become a stage designer while working at a seafood company in Tsukiji. But his interest shifted from stage design to the pursuit of art in a purer sense, and while hopping from one occupation to another he began to teach himself to paint. He also traveled around Asia, North Africa and Europe. Later, in the early 1980s, he enrolled at B-Zemi, an alternative art academy in Yokohama, and under the influence of Shintaro Tanaka, a teacher he met there who was a member of the Neo-Dada Organizers, his inclination towards contemporary art grew stronger. Last time I wrote that the real birthplace of Neo-Dada was not Tokyo but Oita, and in this regard too, Sato’s paintings do a full turn and connect again with Oita while looking back from afar at the Neo-Dada storm that raged in Tokyo in the 1960s. After returning to Oita, Sato formed a relationship with Sho Kazakura, one of the Neo-Dada members from Oita; this being another factor one can cite as to why the “condensation” exhibition should indeed be condensed. Oita Art Plaza, which played a nursery-like role in once again gathering together Sato’s paintings from various locations, was designed by a young Arata Isozaki, who also designed Shinjuku White House, where the members of Neo-Dada assembled in Tokyo and radiated hot temperatures day and night (incidentally, Shinjuku White House has recently been reborn as the alternative space WHITEHOUSE run by Chim↑Pom). Today, as well as containing a reference room dedicated to Isozaki, it also houses a “60’s Hall” showing works by Shintaro Tanaka, Sho Kazakura and others. To borrow a term used by Isozaki, this “condensation” exhibition was by no means a mere retrospective; it was also a kind of “fuka katei (incubation process).”

Given the above, the fact that one can see among the works Sato made in Tokyo while attending B-Zemi pieces that are closer to objects than paintings may be due to atavism from Neo-Dada, which originated in Oita. It was in 1991, after all these trials and errors, that Sato moved back to Kitsuki. Then, between 1999 and 2001, he concentrated on painting while building his residence-cum-studio, Fort Hananoki, in Oga. Until his death in November 2010, he helped out on nearby farms while quietly continuing to paint, keeping the amount of work he did to the minimum required to make a living.

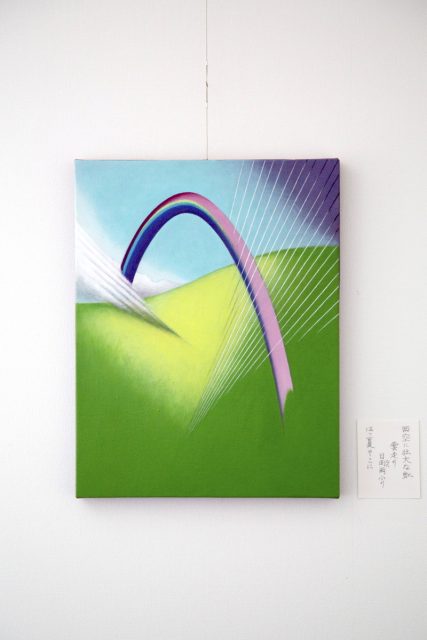

Shunzo Sato – (left) Tanagokoro (The palm of the hand), 2007; (right) A glorious rainbow in the west sky / the clouds scurry / a sunshower / there, are the beginnings of summer, 2007.

In this way, Sato’s daily life and art practice, the land and his body, were connected and became one through farming, art and his lifestyle, with his paintings becoming something like the harvest extracted from this. That one notices here and there motifs reminiscent of plants probably stems from his perspective of daily work and life dealing with the land, but essentially these are starting points and depicting them has not become an objective. The canvases are all large, the colors perfectly clear, and looking at them we are drawn into the color planes. The forms are abstract but do not derive from concepts, and while we cannot specify what they depict, they have a kind of corporeal concreteness. They also have an earthly dimension, as if one were following with one’s eyes the sky, clouds floating in it, the ocean or a range of mountains forming a ridgeline far in the distance, and when I encountered them at “All About Shunzo Sato” I felt calling them somehow universal would measure up favorably as a metaphor. Later, when I looked through the critical biography, I learned that this was not an exaggeration.

Several works from this period are suggestive of a connection with the universe. Shunzo perceived the very existence of humans as nothing but the universe. This thought process is different from such simple-minded ones as my own, given that on hearing the word “universe” all I can think of is darkness and spaceships. It seems Shunzo believed that all life (organisms) irrespective of whether they are flora or fauna are connected to the universe, and he set out to depict this in his paintings.

Hananoki no kaze: Sato Shunzo hyoden, p 31.

I should make it clear immediately that Sato’s paintings are not related to the universe as the outside world. As I wrote last time referencing the title of Sato’s main poetry collection, Niji, natsugusa, dorogame (Rainbow, summer grass, softshell turtle), his route to the universe is possessed of an almost topological inverted dynamism in which a viewpoint at eye level or ground level where mud glistens in the sunlight leads to a perception of the world not as earth but as a planet. In fact Sato’s paintings all have the capacity as picture planes far larger than what might be called the switching of two-dimensional figure and ground. In his paintings, front and back are continually reversing topologically, so that the position of the viewer in front of the work is relativized. They remind one that this earth is at once the ground that remains horizontal, and in a planetary dimension where up and down, left and right do not exist. However, to repeat myself, Sato did not produce these paintings based on intellectual knowledge and theory. They were his everyday life and came about as if exuding from it. He was well acquainted with the ecologies around us that certainly exist but are difficult to see as well as with their changes, and incorporated these organic mechanisms in his work.

But Shunzo loved most dearly the byways. He sought out and walked not the paved roads made for automobiles, but farm roads and byroads, non-legal public roads and animal trails. Even though they may be superior in terms of convenience, roads travelled by automobile never raise one’s spirits. However, as soon as one enters a byway one sees all manner of vegetation growing there. They present to us seasonal changes. Sometimes one even encounters wild boar and other wild animals. Sato couldn’t help feeling happy about such encounters. On one occasion he spoke with delight of coming across a family of over a dozen wild boar moving along in a row.

(Ibid, pp 30-31.)

It is precisely these byways that are connected to the universe. And it is the discovery of them that enables us to experience that the earth is not something that can be understood through horizontal or vertical rational design, but is endlessly divided up by planetary labyrinths, that it spills out from society and the world due to the activity of lifeforms that bubble up from these gaps, and is connected as is to the planet (earth) as the source of life and its cradle. And this experience is extremely similar to the reverberations that remain in one’s body after viewing Sato’s paintings.

Shunzo Sato – Tendo (The ways of Heaven), 2009.

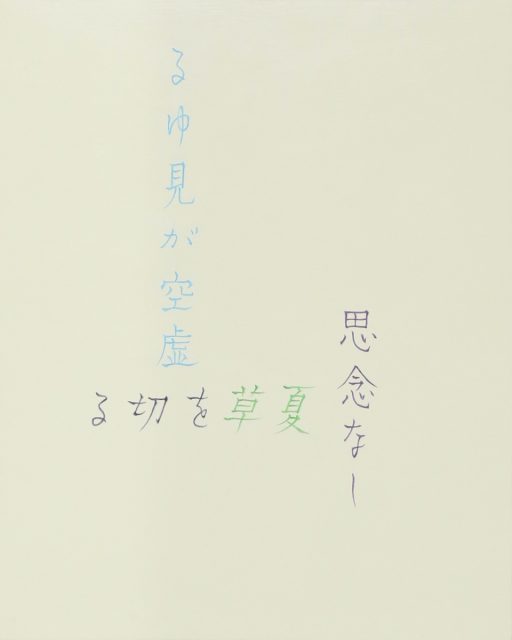

At such a level, the modern, functionalist distinction between words as dealing with meaning and pictures as dealing with images loses any perceptible meaning. In fact, Sato connected painting and poetry inside and out in a very topological way, enabling the two to coexist. And for this very reason his poetry had to be presented not as type but as handwriting. The following verse from Shozo Sato’s critical biography made a particularly strong impression on me, but reading it again, it undoubtedly has the potential for the same kind of physical impact one experiences when viewing his paintings in that the ground and the universe are reversed in front of one’s eyes.

Without thought / I see the empty sky / cutting down the summer grass

Shozo offers the following comments.

Most of the poems I have quoted so far are included in Sato’s poetry collection. This collection is unusual in that the handwritten works are reproduced and printed as is. The handwriting contains the author’s sentiments, including the rise and fall of his emotions. With type, all the words would inevitably have a normal temperature, but with handwritten text, the letters are not confined to the page, so that each word seems to have a life of its own.

Ibid, p 35.

Words do not lose their individual character by being typed using a keyboard. Rather, their presence is enhanced by being written down by hand.

Shunzo Sato – I see the empty sky, 2003.

In any case, Sato’s paintings have survived. But there was a possibility that they would not. For many of the paintings he left behind, there was apparently some discussion about what to do with them after the artist’s death. In the end they all survived, which is why I can write about them here. But Sato’s other older brother, Takashi, had a somewhat surprising proposal. He suggested it might be best to burn the paintings at Itogahama, a beach around a kilometer from Sato’s studio. When they were children, the Sato brothers used to play at this beach until they were tired, in which sense it is truly imbued with the temperature of the land.

Even if it were a joke it would still have been going too far. At the time, I interpreted it as being said out of concern for the burden that would be placed on us in the future. But my older brother’s intent was different. Shunzo didn’t produce his paintings with the intention of leaving them behind; rather, painting represented his way of life. Throughout his life he’d been searching for a “unified path.” And he was on the verge of achieving it. He wasn’t thinking about what to do with his works after reaching his destination, after his death. That being the case, once he’d had passed away, there was no reason for keeping them in this world. As for the method of their disposal, my older brother thought burning them at Itogahama, one of the indelible scenes of Shunzo’s childhood, would be most appropriate. It wasn’t a lighthearted joke; he was quite serious. (Ibid, p 12.)

For a brief moment, I pictured in my mind a scene of Shunzo’s works piled high and burning furiously on a beach at night. And I tucked it away in the realm of the imagination. (Ibid, p 43.)

When I read this, what came into my mind was none other than MOCAF, the art museum that opened as a white revolving door in a corner of Tomioka, Fukushima prefecture after the silent tribute at 2:46 pm on March 11, 2021, the tenth anniversary of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, only to be dismantled and burned as firewood later that same day, and the strange space-time arranged beyond that revolving door. That was a space-time in which art society exhibitions like the “Shunyo Art Exhibition” looked nothing like they once did, and that was where I alighted. There, there were no such distinctions as contemporary art, fine art, Western-style painting and art societies. It was a world where there was only one level of expression in which by being “uncommonly” domestic, art could transcend being domestic, which is to say it could be at once domestic and beyond/domestic. There, I was “reunited,” as it were, with Mine Oka’s paintings and the paintings of Shunzo Sato. Of course, unlike MOCAF, Sato’s paintings did not end up being burned at Itogahama. However, while they were not actually burned, Sato’s paintings were later assembled together at the Hananoki Museum and in due course temporarily removed from this root and guided by many winds to encounter the gazes of unfamiliar people by way of diffusion and condensation at the exhibitions “One Place/Piece” and “All About Shunzo Sato,” so in my imagination I cannot help thinking that such an imaginary burning took place. Surely this constitutes the seeds of the unknown art that has the potential to expand into the universe that still lie dormant in Sato’s painting?

“Rainbow, Summer Grass, Softshell Turtle: All About Shunzo Sato was held from March 17 through 30, 2021, at Oita Art Plaza. The Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum (Hijimachi, Oita) displays primarily works by the artist year round.

Note: Schedules nationwide have been subject to change due to Covid-19. Please check the venue websites before visiting.