Before “Freedom of Expression?”: 2019 for Shusei Kobayakawa, Kikuji Yamashita, and Nobuyuki Oura

Shusei Kobayakawa – Kuni no tate (Shield of the Nation) (1944), color on paper, collection Kyoto Ryozen Gokoku Shrine (entrusted to the Nichinancho Art Museum).

Shusei Kobayakawa – Kuni no tate (Shield of the Nation) (1944), color on paper, collection Kyoto Ryozen Gokoku Shrine (entrusted to the Nichinancho Art Museum).

Late this summer I went to two exhibitions in Tokyo’s Kyobashi/Nihonbashi district, an experience that was accompanied by complex feelings of admiration and deep despair. In both cases the venues were not museums but galleries. One was an extremely rare, sizeable exhibition of works by Shusei Kobayakawa at Kashima Arts. Apparently Kobayakawa did not sell work through commercial galleries while he was alive, and even today opportunities to see his paintings are limited, with this exhibition said to be his first solo show in the Kanto region. What’s more, it was centered on Kuni no tate (Shield of the Nation) (1944), Kobayakawa’s masterpiece painted during the war. This painting was made in response to a commission from the former Imperial Japanese Army, although at the time there was an unwritten rule within the military to the effect that dead Japanese soldiers must not be depicted, as a result of which the army refused to accept it. That it is currently in the possession of the Kyoto Ryozen Gokoku Shrine (entrusted to the Nichinancho Art Museum) may be because it was considered all the more important that it be passed on to posterity as an image of the spirits of the war dead not so much simply because it is a war painting, but because it was rejected by the state as a painting. Yet I question whether this really was a case of the state censoring expression or infringing on the freedom of expression.

Of course, this question is distorted due to “having perspective” from a historical point of view. It goes without saying that the prohibition of censorship and freedom of expression are based on rights guaranteed in the Constitution of Japan that came into effect as a result of Japan losing the war. In fact, during the war, censorship of expression was openly tolerated. One of the reasons we are asking these kinds of questions here and now despite knowing such obvious facts is that Kobayakawa’s painting is different in all respects from other paintings that were once banned due to crackdowns on the freedom of expression. Normally, when we call to mind paintings whose production or presentation had to be abandoned during the war, these are almost always cases of progressive, free expression such as abstract painting or surrealism. However, Kobayakawa’s painting is nothing like this at all. In fact, depending on how it was received, it is the kind of work that was even applauded by the military. Whyever would such a painting be censored? That is my first question. Secondly, why was it in 2019 that this painting of Kobayakawa’s that was once rejected by the state and consigned to historical ignominy finally became so widely known that anyone can see it? This is the second context that makes me question whether the circumstances that once surrounded this painting were really what could be called censorship.

Despite its short length, this exhibition attracted a lot of attention and was even featured on the NHK program Nichiyo bijutsukan (Sunday Art Museum). It was just after this program was broadcast that I went to see the show, and though I timed my arrival to coincide with the opening time of 10am in an effort to avoid the crowd, there was already a constant stream of visitors. Everyone seemed to be there to see Shield of the Nation, which was at the far end of the venue, and after moving forward as one they surrounded the painting, gazing intently at the canvas. Following their gazes, I saw an image of a dead soldier still wearing his uniform, both hands firmly clasped on top of his chest, his face covered with a Good Luck Flag. As a so-called “war documentary painting” it relies heavily on the artist’s subjective interpretation, and cannot possibly be called a “record,” and perhaps it was not only the fear that seeing a fallen soldier would kindle feelings of war-weariness among the Japanese people but also this manner of depicting the subject that induced the army to reject it. From Kobayakawa’s perspective, I think this rejection was a result of him boldly seeking a new type of war painting that could only be realized in the nihonga style, which was far inferior to Western-style painting in terms of achieving the documentary-like realism sought by the military. In the end, however, these efforts were not recognized.

Yet standing in front of this painting today, as if defying the military’s judgment during the war, I sense that it actually has a powerful ability to enhance national prestige. One can also see this to a greater or lesser degree in the expressions on the faces of the people who show up at the gallery to view this painting and gaze at in intently. I wonder how many people actually sense from this painting that war is bad. Rather, I wonder if deep down they feel deep respect for this nameless soldier who became a “shield” for his country and stepped forward to become a “fallen hero.” But this is the very kind of sentimentality that the army rejected in refusing to accept Kobayakawa’s painting. The way people saw this painting during the war and the way they see it after the war are diametrically opposed. It is as if at some time or other between the war period (enhancing national prestige) and today, after the war (war-weariness), the way it is received was reversed. What is happening now to the way we look at paintings?

I wanted to view Kobayakawa’s painting a little longer, but instead I left the gallery, which had become crowded as midday approached, and headed down Chuo-dori towards Nihonbashi. Along the way, the glaring new skyscraper housing the former Bridgestone Museum of Art, now renamed the Artizon Museum and scheduled to reopen in 2020, came into view on my right. Before reaching that site, through a large window in the Toda Construction Building facing the street, I caught a glimpse of the “Tokyo 2021 un/real engine: engineering of mourning” exhibition (curated by Yohei Kurose), due to open in just a few days in part of an office building slated for demolition to make way for yet another new building. Were souls of the deceased being consoled here, too? If so, who were they? With these thoughts still in my mind, I quickened my pace, as I was anxious to get to the “Kikuji Yamashita” exhibition at Gallery Nippon, located on a narrow street I reached by turning left at the next set of traffic lights and heading towards Tokyo Station.

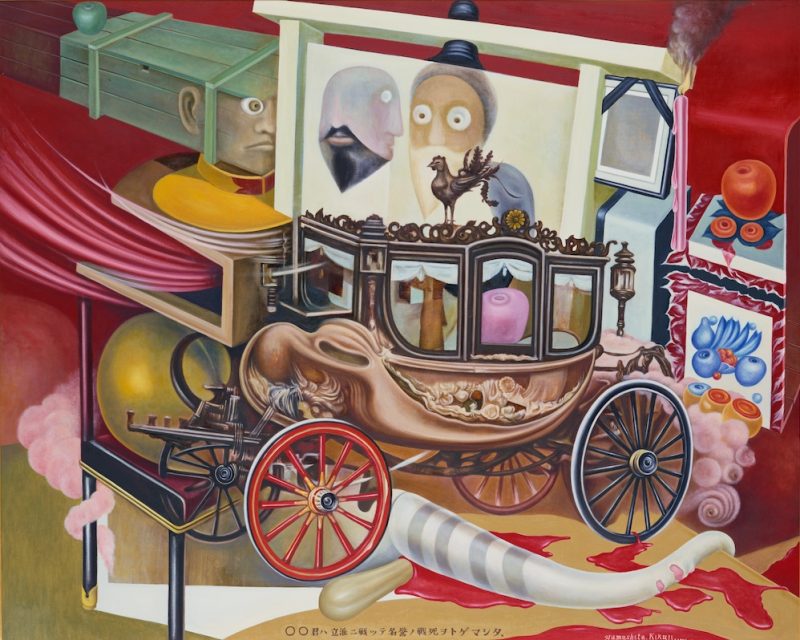

Kikuji Yamashia – Shin Nippon monogatari (The Tale of New Japan) (1954).

Come to think of it, perhaps the fact that (what can be called) memorial solo shows by these two artists, Kobayakawa and Yamashita, opened within walking distance of each other at around the same time is a symbol of the times and not necessarily a coincidence. Because the thing that made me think I had to go to the latter was my discovery on the Gallery Nippon website of the statement, “This year, 2019, is the centenary of his [Yamashita’s] birth. The exhibition includes masterpieces such as Shin-Nippon monogatari (The Tale of New Japan) and Seikatsu sensen (Lifestyle Front) along with rarely displayed oil paintings.” When I read this I could hardly believe my eyes. The writer Hiroshi Noma once heaped the highest praise on Yamashita, rating him “at the upper end of my list of the ten best Western-style painters of the post-war era,” and even now in 2019 there is no reason at all to deny this. Rather, from the point of view of someone who shares the same problems concerning post-war art, it is surely self-evident. Though it is some time ago now, in a poll conducted among art critics and curators to find the top ten postwar works of art from 1945 to 1993 and published in the February 1993 issue of the art magazine Geijutsu shincho, Yamashita’s Akebono-mura monogatari (The Tale of Akebono Village) (1953), came in at number 7 (incidentally, numbers 1 through 6 were as follows: 1. On Kawara, “Bathroom” series; 2. Tomio Miki, Ear; 3. On Kawara, “Date Painting” series; 4. Nobuo Sekine, Phase-Mother Earth; 5. Kazuo Shiraga, Tenisei sekihatsuki (Red-haired Devil); Masao Tsuruoka, Heavy Hand. Yamashita’s work shared the number 7 spot with works by Shusaku Arakawa, Yoshishige Saito and Lee Ufan).

Kikuji Yamashia – Seikatsu sensen (Lifestyle Front) (1955).

Kikuji Yamashia – Seikatsu sensen (Lifestyle Front) (1955).

Kikuji Yamashia – Akebono-mura monogatari (The Tale of Akebono Village) (1953), collection the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

Kikuji Yamashia – Akebono-mura monogatari (The Tale of Akebono Village) (1953), collection the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.*This work is on view through October 20, 2019 in the Museum’s the “MOMAT Collection” exhibition, and is scheduled to be on view again in their collection exhibition held from November 1, 2019 through February 2, 2020.

Given his standing, why, in this truly memorial year marking the centenary of his birth, is there no major Kikuji Yamashita retrospective at a national or other public art museum in Japan? Is there some reason why paintings such as The Tale of New Japan (1954) and Lifestyle Front (1955), which are displayed alongside each other at this tiny gallery and are absolutely indispensable in terms of speaking about postwar Japanese art, are still not in museum collections? Astonishingly, it was not until 2014 that The Tale of Akebono Village, which rates alongside these two works as one of the great reportage paintings, entered the collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. This latest venture at Gallery Nippon was a dizzying display in which masterpieces from Yamashita’s earlier years were arranged together like glittering stars, but to be honest, surely in this centenary of Yamashita’s birth something other than this small gallery space would have been more appropriate. Was no art museum prepared to plan something to try to give an even greater number of people the opportunity to view Yamashita’s paintings and engage in the kinds of discussions we should be having today? What about the Tokushima Modern Art Museum, for example? Tokushima was Yamashita’s birthplace, and in 1996 when Tamon Miki was director it held a substantial exhibition to mark the tenth anniversary of Yamashita’s death that toured the country the same year, stopping at the Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura, the Miyagi Museum of Art and the Itabashi Art Museum. The words of greeting that appear at the beginning of the exhibition catalog in the name of the Kikuji Yamashita Exhibition Executive Committee include the following statement: “The work left behind includes many important items, and could be said to be an indispensable testimony to postwar history. As we look at these works, perhaps we need to listen intently to the voices of the period and try to adjust our own posture accordingly.” Truly these could be read as words directed at us today. Just 23 years after the tenth anniversary of his death, has such sentiment really vanished, and is Yamashita’s reputation really in tatters? Perhaps plans are secretly underway to stage something next year? Curious, I asked someone at the gallery, but they said they had heard nothing of the sort. Nor do there appear to be any signs of planning being underway for a publication of some kind. So whenever did Kikuji Yamashita become a completely forgotten artist? (1)

It was precisely because I practically had the entire venue filled with Yamashita’s masterpieces to myself that I felt so terribly anxious. I hardly saw any information about the exhibition to begin with. The only reason I went was because someone posted on social media a photograph of the exhibition schedule displayed at the entrance to Gallery Nippon. It was not mentioned either in Bijutsu techo online, which is a reliable source of information on the most noteworthy initiatives, or in ART iT. To say nothing of the fact that NHK failed to put together a feature story about it for Nichiyo bijutsukan. To be honest, on the occasion of this exhibition at Gallery Nippon, I really wanted NHK to do a feature story about the centenary of Yamashita’s birth. In a sense, this is in contrast to the situation surrounding the Kobayakawa exhibition, which was the subject of a somewhat unexpectedly put together feature story in what appeared to be an effort to restore his honor to the extent that people flocked to the gallery while the exhibition was on. Had some kind of momentous change of the times occurred without my knowledge? I think I spent at least an hour at the Yamashita exhibition venue. It was right around lunchtime, and the street outside was crowded with passersby. But not one of them opened the gallery door and came inside.

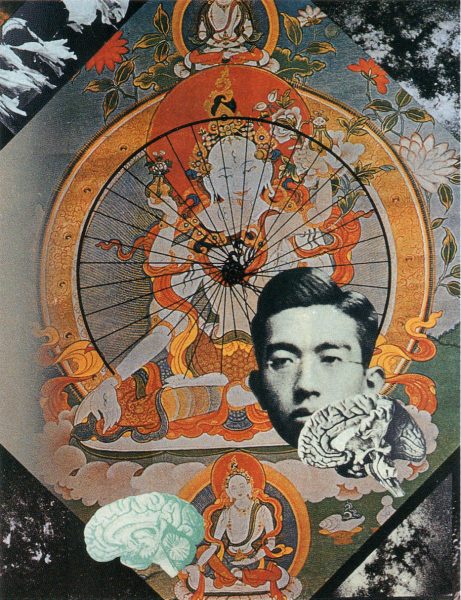

Kikuji Yamashia – Seisha (Holy Carriage) (1971), collection the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo

One reason for this “cold reception” is clear. It is probably not unrelated to the fact that Yamashita produced a series of paintings with Emperor Showa as their motif. In fact, at the 1996 retrospective, none of the works from this so-called “anti-emperor system series” were displayed. Which is no doubt precisely why in the catalog, Masato Ozaki, who was the curator in charge at one of the venues for the touring exhibition, the Itabashi Art Museum, expressly added the subtitle “For a Kikuji Yamashita exhibition to come” to his own text and added a note emphasizing that “This exhibition is not a Kikuji Yamashita retrospective. I think it presents a selection of Kikuji Yamashita’s artworks for a Kikuji Yamashita exhibition to come. But first I would like to state that naturally, some of the responsibility for such a presentation also lies with me.” In taking it upon himself to leave behind a clear statement that the show in question was “not a Kikuji Yamashita retrospective,” but merely “a selection of Kikuji Yamashita’s artworks” for a retrospective (in the true meaning of the term) “Kikuji Yamashita exhibition” that needs to be held sometime in the future, Ozaki was partly expressing his own responsibility for not being able to achieve this, but there is undoubtedly also a desire to entrust this task to those who would follow. So at the 1996 “Kikuji Yamashita exhibition” at least, the fact that such a “lack of freedom of expression” still existed was touched on in the exhibition catalog. And even though it could not be displayed, the fact that one work from the “anti-emperor system series” made its way into the catalog in the form of a plate no doubt represented a modest act of resistance. There, the beginnings of an analysis and critique of this series of works was also faithfully included (in a text by Hikaru Harada from the Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura).

If the above is true, then surely there was no better opportunity to hold this “Kikuji Yamashita exhibition to come” than this year, the centenary of Yamashita’s birth. And if this year was too difficult, the next best opportunity is probably the 50th anniversary of his death (2036). Or perhaps the 150th anniversary of his birth (2069). Then again, those who waited for the “Kikuji Yamashita exhibition to come” to be held on the centenary of his birth waited in vain. This is a reality that cannot be changed. The exhibition staged at Gallery Nippon for just 15 days was the sole opportunity to impress this on the world. But was this serious loss really a result of official censorship? No, such a plan itself did not exist, so there was nothing that could be the subject of censorship to begin with. Because there was no plan, there was also no way to do the self-censorship we hear so much about these days. Here, forgetting, which is so much more worrying than simple censorship or “lack of freedom of expression,” wields its barbarous power to the full, unseen and not pointed out by anyone.

Installation view of “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” at the Aichi Triennale 2019. Photo ARAI Hiroyuki.

Installation view of “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” at the Aichi Triennale 2019. Photo ARAI Hiroyuki.

That I have used the above language is of course because the forced closure after just three days of the “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” exhibition at the Aichi Triennale 2019, which opened before the above two solo shows but is beyond comparison in terms of scale, is in my thoughts. The reason for the closure was the presence in the exhibition of Kim Seo-kyung and Kim Eun-sung’s Statue of a Girl of Peace (2011), symbolizing the harm inflicted on so-called “comfort women.” As a result of the “social media-style soft terrorism” (Aichi Triennale Investigative Committee) directed at this statue – including a vast number of phone calls, some consisting of threats and intimations of murder, that interfered in the running of the exhibition – it was claimed that it had become difficult to guarantee the safety of visitors. Regarding this decision, opinion is divided over whether closing an exhibition on the grounds of such safety concerns corresponds to censorship, which is clearly forbidden in the Constitution of Japan. However, even granting that further investigation is needed to determine exactly what kind of danger was imminent, if priority is given primarily to restricting visitors’ “right to know” on the grounds of ensuring safety in terms of running the event, then it is inevitable that this will be regarded as official restriction of people’s rights, i.e. censorship. To begin with, in terms of chronological order as well as importance, the thing that should be restricted is not a possible “right to know” but “aberrant, unreasonable behavior” (the expression used in the judgment at the first “Emperor collage incident” trial concerning “Holding Perspective” (1982-83), a series of lithographs by Nobuyuki Oura that were also among the targets at “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'”). For example, having become aware of the situation, more than a few artists requested that their work be removed or the contents altered in protest over the official restriction of their undoubted right, or in other words censorship. However, that the majority of the artists who immediately took these measures were participating artists from overseas also highlighted that fact that the points of reference for ways of thinking about censorship and freedom of expression differ greatly in Japan and other countries (it became clear that, in general, Japanese artists tend to attach importance to opportunities for additional dialogue and independent study groups rather than the use of force). At the same time, this triennale was enveloped in a peculiar dynamism the likes of which have never been seen before, with numerous statements from Japan and abroad flying back and forth, press conferences being held in various locations and unofficial opportunities for discussion also being created in a section of the venue. However, it remains unclear whether these activities will actually lead to the reopening of the individual exhibits. (2)

Nobuyuki Oura – “Holding Perspective” (1982-83), set of four prints.

Nobuyuki Oura – “Holding Perspective” (1982-83), set of four prints.

In any case, I think the main obstacle in terms of reopening “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” is not Statue of a Girl of Peace, whose appearance at least is completely ordinary, but Oura’s new video work, Holding Perspective Part II (2019), which includes a scene of the artist burning works from his own series of collages, “Holding Perspective,” bearing photographs of Emperor Showa, and could be regarded as in the tradition of Yamashita. This is not done simply to shock. It goes without saying that people’s emotional resistance to a portrait of Emperor Showa being burned is based on their opposition to harm being inflicted on the state system that has the emperor at the top (in Japanese, kokutai). That being the case, people’s extreme feelings of aversion towards Statue of a Girl of Peace also stem from the same hierarchy. It is precisely because the emperor system lies at the source of such discrimination that even an apparently banal image of a girl becomes a target of hatred. And so the debate around censorship and the responses and discussion around freedom of expression triggered by the closure of this exhibition that do not make an issue of the emperor system are fundamentally ineffective. For example, in the “public broadcaster” NHK’s report on the matter on Today’s Close-up: Repercussions of the Closure of “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” (broadcast September 5, 2019), Statue of a Girl of Peace is shown as a matter of course, but not once is “Holding Perspective” shown (Is this censorship or voluntary restraint? Or is it perhaps editorial rights?). Similarly, independent discussions and learning opportunities that do not mention the emperor system as it is covered in “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” are nothing more than formal art games designed to reassure the world that the participants are “socially engaged.” Moreover, hasn’t it been the very “shams” that are “international contemporary art exhibitions,” including “triennales,” which purport to be the intellectual pinnacle of these art games, that have long avoided (discriminated against) any debate around expression of the emperor system? That the artistic director of this year’s triennale, Daisuke Tsuda, often cites the examples of decidedly “political” international contemporary art exhibitions such as documenta is also probably because he wanted to overcome such “differences in degrees of enthusiasm” regarding these exhibitions in Japan and overseas, something he had become aware of through his work as a journalist, using as a weapon the otherness that only an “outsider” can employ. In fact, the absence of the “Kikuji Yamashita exhibition to come” in 2019 has also occurred in the wake of an accumulation of a pervasive difference in degrees of enthusiasm generated by this country’s contemporary art, which has been swallowed up by events that present themselves as “international contemporary art exhibitions” but are in fact bright, cheerful “art festivals.” To put it another way, it is not because they are “domestic” that artists like Kikuji Yamashita are not suited to international contemporary art exhibitions. The very circumstances in Japan in which artists like Yamashita are not dealt with in similar occasions are “domestic,” and being able to boldly deal with them is something about which there ought to be international solidarity within art by its very nature. That being the case, there is a deep connection between the “Kikuji Yamashita exhibition to come” not being held in 2019 and Oura’s work at “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” not being able to be seen “now.”

At the same time, why was it that Oura felt compelled to submit a new video work despite it being contrary to the spirit of “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” (to display works that encountered difficulties in terms of being displayed in public places in the past)? To begin with, the reason Oura used portraits of the emperor is not because he opposes the emperor system. It would appear that, having once lived overseas, he used the emperor, who surfaced as a means of compensating for a self that was in all respects empty, as one element in a series of self-portraits/collages. However, the state did not accept the completed series of works, “Holding Perspective.” Or rather, to be precise, it accepted it initially but after a flood of complaints and attacks from right-wingers, the Toyama Museum of Modern Art, which had purchased and exhibited the works, stopped showing them in public and sold them to an anonymous individual. They also burned all their copies of the exhibition catalog in which the works were featured. The suit Oura and his supporters brought against the museum as a result of these actions was ultimately dismissed in the Supreme Court. In other words, just as had happened to Kobayakawa earlier, the value of the existence of Oura’s works had in effect been denied publicly by the state. The video work Holding Perspective Part II reiterates the process surrounding this series of rejections by the authorities and does not “target” the emperor at all. To put it simply, it is his position not as a perpetrator but as a victim that is retraced in Oura’s mind. From what position is he able to comfortably exhibit work at such a public forum as the Aichi Triennale without clearly expressing this contempt he had received as an artist? In fact, the court that dismissed all of Oura’s claims at the second trial was none other than the Kanazawa Branch of the Nagoya (home of the Aichi Triennale) High Court.

However, what would have happened if in 2019, an opportunity for the “Kikuji Yamashita exhibition to come” including the “anti-emperor system series” to be held at a national or other public art museum this year had been brewing? In this case, at the least this “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” exhibition, and also probably the “Freedom of Expression?” exhibition (Gallery Furuto, 2015) on which it was modeled, would likely not have existed in the same form. But that does not necessarily mean that the connections that lie at the root of the problem would themselves disappear. In fact, at 2015’s “Freedom of Expression?” exhibition, Kikuji Yamashita’s Tamanori No. 1 (Riding Bullets No. 1) (1972), which depicts Emperor Showa alongside Charlie Chaplin, was displayed together with Oura’s work. In terms of connections, in November of 1986, the same year that “Holding Perspective” became a problem (June), Yamashita passed away at the age of 67, which is three years younger than Oura’s current age. Unless we “hold” them, such “perspectives” cannot be seen. It is because we lose sight of them that the images alone become isolated and the one-sided denunciation begins.

In this sense, in 1996, “perspectives” on history were still alive. At the “Kikuji Yamashita Exhibition” held that year, while the “anti-emperor system series” itself was not displayed, the series “Rebel Army Collages” (1970) that preceded it and “War and the Sayama Case Trials” that followed (1976) were. However, would it actually be possible to exhibit these series by Yamashita today at a national or other public art museum? Perhaps the abnormal situation in which in 2019, the centenary of his birth, not one art museum in Japan will hold a Kikuji Yamashita retrospective is itself the greatest example of “before freedom of expression” that we have been unable to hold on to since during the war when Kobayakawa’s Shield of he Nation was rejected.

Postscript: This column was written on September 25, 2019, at a time when the situation concerning the “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” exhibition was changing moment by moment.

1. On this subject, I found a somewhat concerning article in the Tokushima Shimbun, so I am including a link. “Editorial: Increase opportunities to experience powerful emotions at the Tokushima Modern Art Museum,” Tokushima Shimbun, November 2, 2018.

2. Editor’s note: On September 25, the investigative committee set up by Aichi prefecture to look into matters surrounding the cancellation of “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” expressed the view that the exhibition “should be reopened as soon as possible after the conditions have been satisfied.” Meanwhile, on the following day, September 26, it was reported that the Cultural Affairs Agency had decided to withhold a 78 million yen grant to the Aichi Triennale. On the same day, ReFreedom_Aichi, a group comprising artists participating in the triennale, launched a petition at Change.org calling for the reinstatement of funding for the Aichi Triennale. As of September 30, more than 90,000 people had signed this petition, which included the message, “Stop the Cultural Affairs Agency killing culture.” As well, since the Cultural Affairs Agency’s decision to withhold funding was reported, people have gathered in front of the Agency’s headquarters calling for the repeal of this decision. On September 30, the Aichi Triennale Executive Committee and the “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” Executive Committee agreed to reopen the exhibition. The reopening would occur sometime between October 6 and 8, with discussions between the two parties expected to continue. On October 8, 2019, after the writing of this article, “After ‘Freedom of Expression?'” reopened for the first time in 66 days, a week before the end of the Aichi Triennale. Visitors were issued a numbered ticket, and based on a lottery, were allowed in to see the exhibition one group at a time.