From oil painting to Ko-Kutani – Inosuke Hazama’s pursuit of modern painting

The Inosuke Hazama Art Museum (Kaga, Ishikawa). All photos courtesy the Inosuke Hazama Art Museum.

The Inosuke Hazama Art Museum (Kaga, Ishikawa). All photos courtesy the Inosuke Hazama Art Museum.

Last June, after staying the night in Kanazawa following my participation in a discussion at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art with guitarist Shin Sasakubo, leader of the Chichibu Avant-Garde, I set out the following morning by train for Kaga Onsen Station on the Hokuriku Main Line, planning to visit the Inosuke Hazama Art Museum in Suisaka, Kaga. I mentioned this at the drinking party the day before, but even an art insider I knew who has lived in Kanazawa for a quarter of a century hadn’t heard of it. Another person had been to the museum once several years ago. They assured me it was an interesting place, but I got no real mental image of it at all. I was curious as to what sort of place it would be. I called to mind this exchange as I sat in the train looking out the window at the passing scenery. Before long we arrived at Kaga Onsen. It goes without saying that the station was completely unfamiliar to me. Because the name of the station included the word “onsen,” I imagined it would have some charm, but the exact opposite was the case. After passing through the station building, rendered maze-like due to ongoing construction work, I climbed in a taxi still feeling slightly anxious and told the driver where I wanted to go. He seemed to know the place, which came as a relief. But soon after setting out we left the city center and headed further and further into the country, and after passing over a large bridge from where I could see a group of people cutting grass we entered a hilly area before finally ascending a steep incline. I thought the driver was going to be kind enough to take me all the way to the entrance, but before reaching the top he stopped the meter, saying he couldn’t go any further, and I ended up having to walk the rest of the way. Luckily I could see a sign for the Inosuke Hazama Art Museum just up ahead, and was able to reach my final destination without getting lost.

The crest of the hill seemed to be choking with greenery putting on a growth spurt before the onset of the rainy season. At the entrance to the magnificent wooden Japanese-style building was a tasteful sign welcoming visitors to the Inosuke Hazama Art Museum. But for some reason there didn’t seem to be any people about. Sure enough, as I got closer I noticed that a “Closed today” sign was displayed. For a moment I gave up hope, though it was something that was relatively common with private art museums. Given the long journey, I had made thorough preparations, including checking the schedule several times. I decided to wait a while until someone appeared, but then I noticed an intercom next to the entrance. I immediately pressed it, whereupon a man’s voice announced that he would open the door for me. After everything I had been through, I finally felt a sense of relief.

Why go to all this trouble to visit this place? Let me explain the reason.

In 2015, in collaboration with the artist Makoto Aida, I published Sensoga to Nippon (War paintings and Japan) (Kodansha), which contained a dialogue between Aida and myself on the subject of so-called “war campaign documentary paintings,” aka “war paintings,” during the Pacific War (for more, see “Notes on Art and Current Events 76“). That in itself was a good opportunity, but one of the war paintings we chose to include in the book (it was actually selected by Aida, who responded to the somehow relaxed mood of Japanese war paintings) was a massive oil painting by Inosuke Hazama (1895-1977) called Closing in on Lin-an (c. 1941, on indefinite loan to the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo). Both of us wrote brief commentaries on this painting, but mine resulted in the Inosuke Hazama Art Museum contacting the editorial department to suggest I had misunderstood Inosuke’s achievements as a painter. I had viewed his move from Tokyo to Kaga after the war to devote himself to Ko-Kutani ware as an extension of his pursuit of highbrow tastes arising from a leisurely lifestyle, but I now accept that this was due to my own negligence.

To begin with, would Inosuke, who was born and raised in Tokyo and later lived there for many years, really put aside his regular job and not only leave to live in Suisaka, Ishikawa, a place he had no connection with, but establish a kiln in the mountains there to pursue a hobby? In Inosuke’s Ko-Kutani ware, or more accurately speaking in his devotion to Ko-Kutani ware, one can detect something extraordinary. Having come to sense this at some point while looking through the material the Inosuke Hazama Art Museum sent me, I decided that in the not too distant future I had to travel to this place that Inosuke moved to and never sought to leave until his eventual death and visit the museum dedicated to educating people about his work. However, while I continued corresponding with Koichi Hazama and Kimiko Amabe, who together run the Museum, I was so busy I was unable to realize this. Until June, that is. For me, it was a “detour” with special meaning and worthwhile even if it meant returning home via a different route.

Interior view of the Inosuke Hazama Art Museum.

Interior view of the Inosuke Hazama Art Museum.

I was left waiting at the entrance for around five minutes. The museum director, Koichi Hazama, arrived having climbed the slope, and after a rushed preliminary greeting he quickly unlocked the door and showed me in. Inside it was roomier than I imagined and the air clean. According to the director, an extremely experienced, skilful master carpenter built it more or less on his own by incorporating modern techniques into traditional Japanese wooden architecture. Incredibly, there was not a single pillar to obstruct the view inside the generous space. It had earthen walls and plasterwork to absorb moisture without creating an oppressive atmosphere. Natural light was introduced via the ceiling, thereby avoiding the cold impression typical of artificial lighting. It was in this space that Inosuke’s paintings, both large and small, dating from the pre-war to the post-war period, were displayed together with works produced after he concentrated his energies on Ko-Kutani ware. There was also a wide selection of related material. The current display was put together on May 1 and was due to continue until March 31 next year. The collection was so extensive that even in such a large space the exhibited works could be replaced several times. I greeted Kimiko Amabe, who had arrived unnoticed at some point, and apologized to my two hosts for the ingratitude I had displayed in not visiting earlier and for my former negligence. Then I listened as they explained the background and history of the museum and about the significance of Inosuke’s decision to give up oil painting and devote himself to Ko-Kutani ware. We were also able to exchange opinions. I don’t have the space here to go into the details of the difficulty of that journey, but embedded throughout it were ideas that I knew would help deepen my thinking with respect to “art in the Japanese archipelago,” a subject about which I have been thinking a lot in recent years, or should I say continually since the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami.

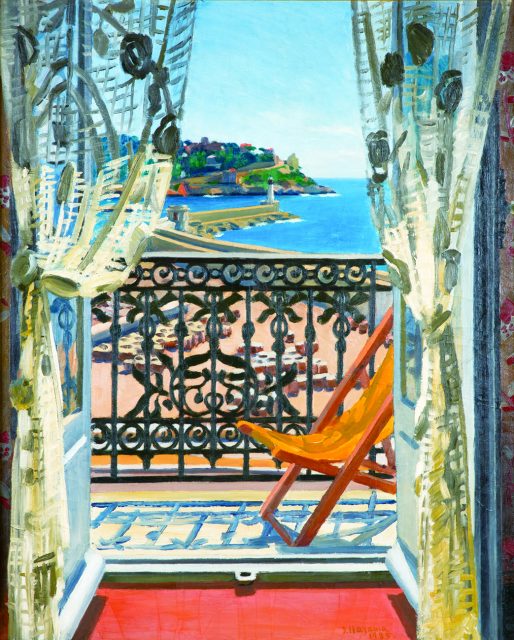

Inosuke Hazama – From the Room (A Balcony in the South of France) (1935), oil on canvas, 72 x 91 cm.

Inosuke Hazama – From the Room (A Balcony in the South of France) (1935), oil on canvas, 72 x 91 cm.

Before I go into that, however, I need to give a brief outline of the artist Inosuke Hazama. Such is the infrequency with which his name is mentioned by art insiders. Which is surprising since at the age of just 17 he participated in the first Hyuzan-kai exhibition (1912) and competed against the likes of Ryusei Kishida and Testugoro Yorozu. Later, in 1921, he traveled to Europe together with Narashige Koide and Hanjiro Sakamoto for the purposes of mastering oil painting, the first of four trips he would make to that continent during his lifetime. It was in Europe that he got the opportunity to meet Matisse, who became his teacher, and the relationship between the two continued for many years. Indeed, if it had not been for this close connection, the 1951 Matisse exhibition, which contributed greatly to modern art taking hold in post-war Japan, as well as the later Picasso, Braque and Van Gogh exhibitions, would not have been realized. Inosuke worked tirelessly not only on his own practice but also on promoting modern art nationally, including acting as the translator for the Iwanami Bunko version of The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh. He also contributed illustrations for publications by such writers as Masuji Ibuse and Fumiko Hayashi, and worked on the design of numerous books. So how did such an artist become so far removed from our collective memory?

The main reason is probably the change in his practice during the second half of his life. After the war, in 1950, as if he didn’t care about the status he had achieved as an assistant professor at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts responsible for teaching young people and president of the Japan Art Association, he quit his job at the school and traveled again to France at the invitation of Matisse, and from around the time he returned home (1951) he began making polychrome porcelain (Kutani ware). In 1959 he established a porcelain section within the Issui-kai art association, and in 1962 he moved to Suisaka near Daishojimachi in Ishikawa Prefecture (near the center of present-day Kaga), a location with a close connection to Ko-Kutani ware, where he established a kiln, completely immersing himself in the world of Ko-Kutani ware. Finally, in around 1970, he quit making oil paintings altogether and until his death in 1977 at the age of 82 he devoted himself completely to exploring the pictorial world arising from the arrangement and harmony of the colors of Ko-Kutani. But what did he hope to achieve by doing this?

Inosuke Hazama – Square dish with Tone floodgate design, porcelain with overglaze polychrome enamels, Kutani style (1975), 15.2 x 15.2 cm.

Inosuke Hazama – Square dish with Tone floodgate design, porcelain with overglaze polychrome enamels, Kutani style (1975), 15.2 x 15.2 cm.

Inosuke Hazama – Plate with Kutani overglaze enamel design, “Newspaper” (1973), diam. 11.5 cm.

Inosuke Hazama – Plate with Kutani overglaze enamel design, “Newspaper” (1973), diam. 11.5 cm.

The most common misunderstanding, and one I previously fell into, is that it was a kind of role reversal in which Inosuke’s interest deepened and he became absorbed in ceramics to the extent that he gave up the most important thing, that is, oil painting. What is fundamentally wrong about this is that until the very end Inosuke continued to explore the essential appeal of oil painting: the production of colors and the arrangement of pigments in a way that utilizes them to the maximum. To put it another way, the reason he once studied oil painting so earnestly was not to acquire the techniques of oil painting itself, as was the aim of the mainstream Japanese art world, but to address the issue of how he could demonstrate in a natural way in his own work the peculiar appeal of oil painting. However, despite the fact that they are the same pictures, the colors of oil paintings viewed in Japan and those viewed in Europe are somehow different. Have you ever felt that a picture looks different from what you expected? I know that I have. In particular, a scene of a dry landscape like that of Arles in the south of France viewed through air containing hardly any moisture has a vividness that puts to shame the mirage-like visibility in Japan during the rainy season in which the landscape itself appears to faintly float behind a curtain of moisture. As seen in the work of Cezanne, Picasso and Matisse, modern oil paintings were produced on the assumptions of such a dry atmosphere and the contrasts that relentlessly and sharply traverse it. Having studied under Matisse, this is something of which Inosuke should have been painfully aware.

In fact, in a letter to Inosuke, Matisse wrote, “Every country has its own beauty, and in the end that prevails.” This would suggest that in a climate like that of the Japanese archipelago, one need not necessarily seek in oil painting a harmony comparable to oil painting that derives from the fixation and balance of colors. As Matisse indicated, in the Japanese archipelago there is a beauty that originates in the Japanese archipelago’s climate and techniques that abide by it that have existed since long ago, and it would make sense to consider these as a route for searching by different means for the quintessence of oil painting in Japan. If so, then Inosuke was destined to encounter Ko-Kutani ware. Where else would true colors lie other than in the cycle of the seasons in the land concerned, in the breathing of the flora and fauna that live there, and in the lifestyles led by drawing upon these diverse blessings? Assuming that is the case, then surely the only option is to live in that place. Inosuke’s choice was not a change of profession, but rather a deepening of it within the Japanese archipelago and a necessity for the purposes of pursuing modern painting in the real sense of the term, which is more than simply importing or acquiring techniques.

One can immediately understand this if one looks at the Ko-Kutani works Inosuke devoted all his energies to creating. The transparent yet powerful vividness of the colors achieved by applying pigment to the large plates that served as his supports and firing them, the balance created by adjacent colors in which neither dominates, and above all the animated sense of energy that only exists in vibrantly breathing life forms and arises from scenes of natural landscapes or daily life observed and depicted down to the smallest detail, are all of a dimension that ultimately could not be achieved in Japanese oil painting. This work was temporarily interrupted by Inosuke’s death, but was later taken over along with the artist’s living space by his successors, Koichi Hazama and Kimiko Amabe, who continue to pursue it diligently. It may be called a museum, but the Inosuke Hazama Art Museum is more than a simple institution. It is a special place that tries to introduce in a bodily fashion as if it were a heart the “blood flow” of such a pursuit to the art of this archipelago.

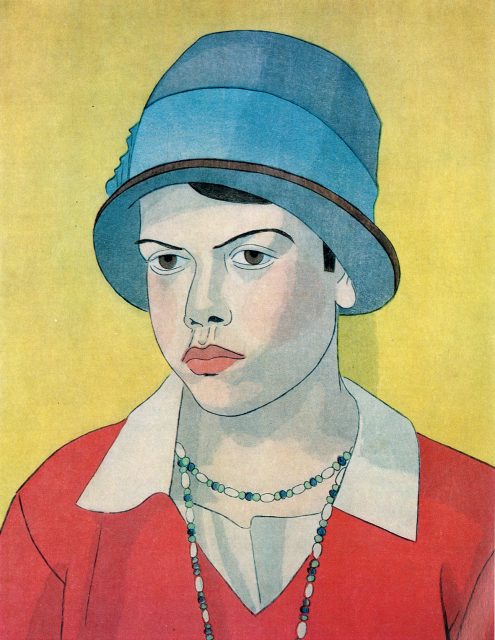

Inosuke Hazama – Country Girl from Southern France (1931), woodblock print, 39 x 29.5 cm.

Inosuke Hazama – Country Girl from Southern France (1931), woodblock print, 39 x 29.5 cm.

There is another area of creative endeavor in which Inosuke ran counter to the mainstream Japanese art world. This stemmed from his belief that art was something that was not created alone by talented individuals. Inosuke learned this from traditional Japanese multicolored woodblock prints. Certainly, in the case of the ukiyoe of the Edo period, there was a division of labor within individual publishers with painters, carvers and printers each honing their skills and working together. To put it another way, it is beyond question that unless this were the case, it would have been impossible to produce such amazing brightness and harmony of colors. Ironically, it was not in Japan but in faraway Europe that he came to realize this. At the time, people in Japan regarded Western techniques as advanced and thought that following them was akin to the progress of civilization. There was disdain for ukiyoe, which people were unable to view as respectable art. However, modern painting of the period was shocked by the two-dimensional picture planes, composition and color arrangement of ukiyoe, and was able to discover truly visual painterly space in the survey-like, flat picture planes that attached importance to the accuracy of perspective, so in fact their priorities were grossly wrong. However, those who were captivated by a simple progressive view of history in which mechanical learning was easy were unable to see this. Inosuke was one of only a handful of Japanese painters who were able to understand this through a process of reverse irradiation from faraway Europe to Japan via his teacher Matisse.

In light of this, it stands to reason that having loosened the shackles of the ego’s insatiable hunger for art – one of the diseases of modernity never satisfied by any amount of appreciation – Inosuke was naturally drawn to the world of Ko-Kutani, the core of whose beauty, like ukiyoe, lies solemnly in the division of labor and the joy of the harmony arising from this. In fact, following the principles of modern art, Inosuke, who discovered the possibilities of the above by way of ukiyoe, at one point attempted to master the entire printmaking process himself, and more than twelve woodblock prints resulting from these efforts survive. But how do they compare to the work of the ukiyoe artists Inosuke particularly admired, such as Harunobu, Utamaro and Hokusai? These works are part of the movement referred to as sosaku-hanga, or creative prints, which has suddenly attracted attention in recent years, and while it is good when a neglected history is rectified, after passing through his sosaku-hanga phase, Inosuke didn’t forget to look back and see that there was a lofty dimension of art that could only be achieved through the division of labor and collaboration.

The possibilities of “painting rooted in polychrome porcelain,” which Inosuke opened up through his completely independent inquiry that involved recreating in the climate of the Japanese archipelago the essence of oil painting by way of Ko-Kutani ware, are being preserved and passed on to future generations by his former apprentices, Koichi Hazama and Kimiko Amabe, and by the Inosuke Hazama Art Museum and the Kutani Suisaka kiln. And these efforts are sustained not by the public via taxes or by corporate money, but by members of the “supporters’ association” who respond sympathetically to the strong will of the pair and the unparalleled world of beauty Inosuke left behind. Certainly, nearly everything about the Inosuke Hazama Art Museum is different from a normal museum. However, it is also an undeniable fact that one can gain there both a deep sense of ease and a profound actual sense of how this kind of art museum is what is needed in Japan.

The Inosuke Hazama Art Museum (Kaga, Ishikawa)

4-3 Suisakamachi, Kaga, Ishikawa

http://inkaga.net/hi/