III.

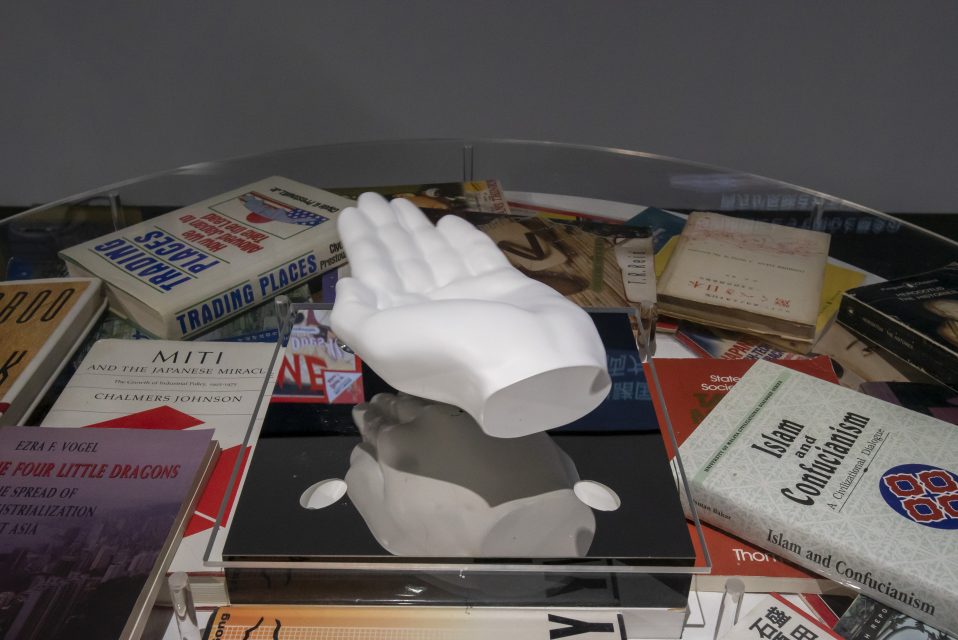

Asia the Unmiraculous (2018- ), detail, lecture and video installation with digital prints on paper mounted on LED-illuminated acrylic, books, and magnetically levitated hand model. All images: Unless otherwise noted, courtesy Ho Rui An.

ART iT: It seems to me that the Western episteme, which has de facto become the international episteme, can be thought of as a kind of artificial intelligence. It takes itself as its own object of inquiry, so all of our attempts at criticality, which are in fact rooted in the episteme itself, only keep expanding the episteme further. The more we try to escape from it, the more it expands.

HRA: Farish Noor’s talk for “The Breathing of Maps” was super-instructive in this regard, because he was talking about mapping as a vital 19th-century technology for imperial domination. As I was listening to him, it became clear how pivotal the 19th century was in forming these epistemic structures that are still the primary modes by which we know the world today, from maps to calendrical time. And since they have become so paradigmatic, it will take a lot to move away from them. I feel that overtly culturalist arguments that distinguish between, say, Asian and European conceptions of time only further obscure how deeply the European imaginary has been entrenched in our institutions, such that virtually no culture in the world can voluntarily exempt itself from its hegemony. Dismantling this hegemony is definitely not something that can be done within any individual practice, but I think asking questions about it—and at least identifying potential moments of rupture—is a good place to start.

ART iT: What were some of the intellectual keystones for you in building your own sensibility?

HRA: I come from a more visual culture media-theoretical academic background, but I did my masters in anthropology at Columbia University in New York, so that also informs my methods. It was during my study of anthropology that I started looking at the lecture as a discursive form for presenting my work. The first full-length lecture I did, Solar: A Meltdown, dates to that time.

I’ve always been fascinated by thinkers who are able to work with images, and one of the reasons I turned to anthropology is that I find that the images I’m most interested in circulate outside the art world. Many of the images I use are drawn from cinematic history, but the images that inspire me the most tend to come from what I would call vernacular cinema. In Asia the Unmiraculous the most significant example is the Coin Test China High-Speed Rail video. This is a genre of videos that started appearing on the internet in 2015 in response to China’s ongoing investment in high-speed rail infrastructure. In each video, which is often captured by a tourist or foreign traveler using the Chinese high-speed rail network, a standing coin is balanced on the ledge of the train window to test the train’s stability. I find these videos absolutely cinematic. In a way, they offer a kind of countershot to another genre of videos that I was looking at in my earlier work DASH, which are the videos shot by dashboard cameras or dashcams. The dashcam is a new cinematic apparatus, and with a new apparatus comes a new mode of perception. What are the broader implications, political or otherwise, of such new modes of perception?

The most provocative texts I’ve read addressing this question are written by anthropologists attending to the ways such vernacular cinematic practices are given form, extended and refigured by the social environments through which they circulate. I learned a lot from my teachers at Columbia—especially Rosalind Morris, John Pemberton, Marilyn Ivy and Brian Larkin.

ART iT: You have a playful approach to language, with many of your ideas flowing through word associations.

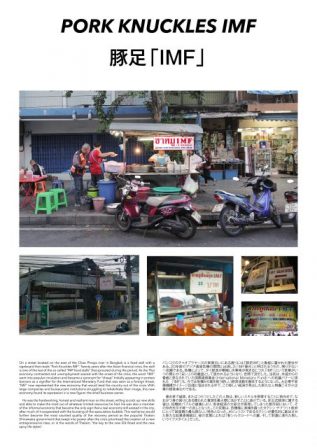

HRA: I try to follow the movement of signifiers, sometimes by way of their contiguous associations, sometimes by just attending to the form of the word itself, as with the abbreviation IMF—taking the literal letters as my starting point and on that basis connecting the International Monetary Fund to the Impossible Missions Force from the Mission: Impossible film series and seeing where that leads me. I enjoy making such lateral connections rather than just analyzing a word on a purely semantic level. Partly because I think language itself operates by way of lateral flows. In Thailand, the word IMF entered popular usage during the Asian financial crisis and became a synonym for “cheap.” I think the foreign origin of the word, or what Vicente Rafael calls the “promise of the foreign,” is what opens the word itself to becoming a carrier for new meanings. It might be productive then to think about all words as harboring this promise, as it might open us toward new ways of seeing the world that words are meant to represent.

ART iT: How much of your research gets left out of the lectures?

HRA: A lot, actually. The process usually starts with a lot of reading and watching films. I will watch anything that I think might be remotely related to my subject. For instance, at one point in my research for Asia the Unmiraculous, I started watching all the Sean Connery films, simply because he appeared in one film, Entrapment, that I mention in the lecture. I really wanted to include You Only Live Twice, which is set in Japan with the younger Sean Connery, and connect it to the older Sean Connery in Malaysia in Entrapment. But it was hard to fit it into the narrative.

So basically I begin with a very broad premise and accumulate material to the point where some tropes start to emerge—for instance, Sean Connery. Then I try to follow the lines of thought that these tropes open up to me. At some point these lines start to take shape as a narrative, and usually this is a very long process that can last over a year.

Both: Asia the Unmiraculous (2018- ), detail.

ART iT: In this case, you were physically moving between far-flung points in the globe for your research: Piraeus, Yamaguchi, Bangkok. Is that something you’ve done at this scale for previous works?

HRA: Compared to my previous works, this project has required the most on-location research—partly because of the dearth of images about finance that I mentioned at the beginning of our conversation. There are many images about the fallout that followed the financial crash, but very few address the political economy of global finance itself. So one reason for going to the places I visited was to look for something that might not actually be there or might not be very visible from the outset. Furthermore, this work is very much about the present, and so revisiting some of these sites that were significant during the miracle and crisis period is something I felt was important to my process. So much of the work is about the dialectic between miracle and crisis that is still unfolding as we speak. And as I allude to in the lecture itself, there is a new discourse of the Asian miracle anchored by a new protagonist, China.

ART iT: The polarities are constantly shifting. For example, colonies like Hong Kong and Singapore were once forward operating bases that were very much in a center–periphery relationship with the metropole. And now, with the rise of China’s economic clout, we might conceive of them as being at the forefront of the global financial system, whereas Europe is lagging behind.

HRA: In that sense, Singapore is in a strange position. But it would be delusional to imagine that it can acquire the status of a hegemonic power in the world or even the region, however powerful it may be in economic and military terms. At best, it’s a mercenary operating within a global system which currently finds itself with little space for maneuver as it attempts to manage the competing interests of the actual hegemons of the region that are China and the US.

ART iT: But Singapore, as I understand it, has also tried to advance neocolonial strategies in other parts of Southeast Asia by investing in economic infrastructure and trying to establish a cultural hegemony over the region.

HRA: Yes. In fact, the relationship to the region is one of direct extraction, whether in terms of labor or even the land on which we live. It is well known that land reclamation in Singapore depends on the city-state’s ability to exploit the environmental resources of its neighbors. Of course, a lot of this has to do with Singapore’s economic muscle, and to that extent Singapore is not so different from Japan in terms of its relationship to Southeast Asia. But I think the bar has to be higher if we are talking about hegemony. One key aspect to being a hegemon is the exporting of ideology, and for all the interest in the “Singapore model,” which has in fact been taken up by many cities in China, you don’t see this translating into the city-state meaningfully setting the agenda at a global or even regional level. I think it’s more useful to think of Singapore as a laboratory from which larger powers extract lessons on how to perfect their techniques of social control.

ART iT: Since Asia the Unmiraculous is centered on the financial crisis of 1997, contemporary China does not play such a large role in the work, although you end on the image of the coin test video. Do you see yourself turning to China next?

HRA: China is the ghost that haunts the whole lecture. I begin with it, but then don’t address it for most of the duration of the work. And that in itself is reflective of the entire discourse of the Asian miracle. If you read the World Bank report on the East Asian miracle, which was published in 1993, just a year after Deng Xiaoping’s Nanxun tour of southern China, there are all these allusions to China, but it’s clear that few economists anticipated how quickly the economy would “take off,” to use the vernacular of the time. So in a way the structure of the lecture reflects the region’s historical relationship to China.

But China’s economic miracle as a subject in itself is also one that demands its own series of lectures to unpack. I find many of the current commentaries on China to be a little hasty and incapable of accounting for the uncertainty that we are faced with. To a large extent the liberal media still draws heavily upon imaginaries from the past when they talk about China today, and naturally many of these tropes are indebted to a 19th-century capitalist industrialist imaginary. I think much of what is happening in China demands new conceptual frameworks.

Asia the Unmiraculous (2018- ), detail. Photo Yasuhiro Tani, courtesy Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media.

ART iT: I’d like to wrap up with a small detail. The hand in the performance is floating by magnetic levitation, which evokes the maglev train under development in Japan, and you end the lecture with the coin test video, which has a kind of screensaver feel to it. The two images suggest the idea of suspended animation. We’re used to thinking about the world in terms of historical development, but perhaps suspended animation—which could also refer to something that is dead but not dead, as well as something that is moving but not moving—could be an alternate way of thinking about where we are at the moment.

HRA: I like that you point out the magnetic levitation and its relationship to the train. One of the books I include in the installation is Shintaro Ishihara’s anti-Western nationalist polemic The Japan That Can Say No. One example Ishihara gives of Japan’s ascendancy over the West is the levitation height achieved by the Japanese maglev train, which I think was eight centimeters at the time, exceeding that of the German trains. While in the colonial era it was the breathtaking speed of the train that was a signifier of power, for Ishihara the height at which the train could be suspended above the tracks became the new index of economic supremacy. And now you see in the coin test videos how stability has become the new signifier of technological advancement. It is an image that holds up the fantasy of the Chinese state as a stabilizing force at a time of financial volatility. This is a fantasy that is often purveyed by certain elements of the West who look at China and imagine that it can provide a solution to the current global crisis.

ART iT: We end on an image of inertia, basically.

HRA: Or repose. The ability to not move, even when you are moving. That has become a privilege, if you think about the trends in global migration. These days the people who often have to move are those who are in a precarious condition, such that not having to move, or moving in repose, is actually the ultimate sign of privilege. I guess that is what is so attractive about the image of the coin test.

I | II | III

Ho Rui An: Image Crisis