Performance of Reanimation in Celebration of Kyoto Prize Laureate Joan Jonas, Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

Performance of Reanimation in Celebration of Kyoto Prize Laureate Joan Jonas, Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

Putting Oneself in the “Midway Time,” Where Live Humankind, Glaciers, Flora, Weather, and Planets: Review of the Joan Jonas Performance and Exhibition in Celebration of the Kyoto Prize Laureate

Kyoko Iwaki (theatre and performance studies researcher)

A theatre performance that consciously deals with its fundamental temporal nature is a rare thing. Time forms the foundation of the viewing experience. Why is it, then, that only a few artists attach importance to that base? One reason is the directorial misstep, arising from losing the bird’s-eye view that considers why the ornamental musical notes of dialogue and gesture are inscribed on the score. Or perhaps it is the manifestation of a torpor whereby our sense of crisis, our feeling in life that time is finite, has weathered with the years. Created, performed, and with stage design and video projections by Joan Jonas, who has been based in New York since the second half of the 1960s, Reanimation (December 12, 2019, ROHM Theatre Kyoto South Hall) was a multimedia performance that responded with remarkably acute sensitivity to various standards and measures of time.

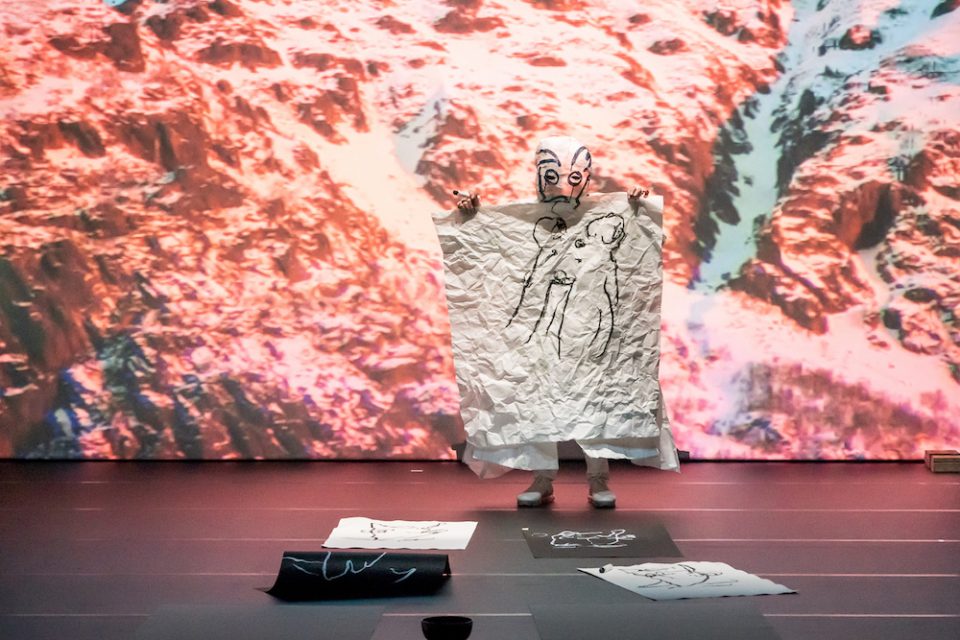

The onstage performers number just two: the small-of-stature Jonas, like a young girl dressed in a modern white costume made with Japanese paper; and the jazz pianist Jason Moran, sitting at a giant Steinway. (Another woman, who functions like a stagehand removing the props, does not appear as an actual performer.) Matching the music that Moran plays with great vigor yet dignity, Jonas starts the performance by using chalk attached to the tip of a long stick to sketch snow crystals on a blackboard standing in front of her. Simultaneously, on the large screen behind, is projected the frozen scenery during a blizzard, shot by Jonas when she stayed in the Norwegian islands of Lofoten. The visual whiteout projected in the background, the auditory overload of the improvised piano performance, and the unhesitating, light brushwork from Jonas provide multilayered stimulation to the synapses in the brains of the audience.

The time until the sketch is complete, a time of humankind, of glaciers, of flora, of weather, of planets, and of the reverberating piano, or the time of the performance that the audience senses, can all be expressed in the same word “time,” but like snow crystals, are actually plural and not the same, single “time.” And yet, though it seems simultaneously contradictory, it is also a fact that time is something equally ephemeral for all sentient beings. Here, borrowing the aged body of Jonas exposed onstage, the rich plurality of time and the ephemerality of dying creatures intermix and are projected at the audience. Or rather, the art time, flawlessly arranged like precision machinery, and the fragilely disordered living creature time that unavoidably emanates from this, simultaneously surge in all at once.

Performance of Reanimation in Celebration of Kyoto Prize Laureate Joan Jonas, Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

Performance of Reanimation in Celebration of Kyoto Prize Laureate Joan Jonas, Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

The expression “glacial time” is used to describe a sense of time changing slowly, so much so as to be imperceptible to humans. When audiences or viewers tell her that her work is too difficult to understand, Jonas apparently often gives the following advice: “Take your time.” And indeed, this work encourages us to go beyond our regular senses and take our time when viewing. We slowly, carefully turn our eyes and ears to the passing clouds, the gushing water, the melting icebergs. “Are you sure the lilies of the field are silent? If a sensitive enough microphone were placed beside them?” Borrowing these words by the Icelandic Nobel laureate Halldór Laxness, Jonas speaks into a microphone in a level voice construable as both resignation and anger.

As demonstrated in the life she has lived as an artist emphasizing, among other things, deliberation, process, and ephemerality in New York, a hypercapitalist society that conceptually prioritizes speed, results, and productivity above all, Jonas advocates, in a sense, the limits of right-wing accelerationism. We cannot avoid the sixth mass extinction now taking place in the Anthropocene by extreme speed or technological development, she tells us physically. To illustrate this through one scene from Reanimation, there is the act of Jonas using chalk in her hand to trace the outlines of the footage of mountain ranges, glaciers, fields, clouds, animals, and so on projected behind her. This is surely a metaphor for the activity that humankind has engaged in across history of trying to control nature. But Jonas knows full well that the act is simply abortive. This is because at just the moment you think you could finally capture the outline of something from nature, it slips away like a handful of sand trickling between your fingers and mercilessly shifts into a different form. To put it another way, nature is controlled by the god that is time and people are unable to stop this time. We merely go always hither and thither according to some kind of “process.”

Process could also be described as “impermanence.” It is feasible that Jonas has employed in her work various aspects of Japanese traditional performing arts such as Noh, Bunraku, and Kabuki after her first visit to Japan in the 1970s due to being intensely captivated in some form or other by such a Buddhist notion of time as impermanence. That urge in her early period, of course, might also have come from her dialogue with artist peers like Richard Serra, Robert Smithson, and Robert Morris with interests in process art (that is, art that emphasizes the process over the ultimately finished form). Or possibly it was from her exchange with choreographers such as Trisha Brown and Merce Cunningham who utilize time in their practice. Jonas, though, more than those aforementioned fellow artists, has truly endeavored to embody the mutability, ephemerality, and impermanence of time. Curiously, perhaps due to succeeding brilliantly in this endeavor, Jonas has been regarded as an “unfocused” artist and did not hold a major solo exhibition even in her home country until the twenty-first century. (This might also be the result of having acquired by then a degree of authority after taking up a teaching position at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1998.) Jonas, however, knew: in order for women to evade being swept up into the historical narrative that men weave, they have no choice but to express the colloquial over the written, the mask over the human, the impermanent over the permanent. This is already evident in Organic Honey’s Vertical Roll (1972), an early work included in the exhibition at Kyoto City University of Arts Art Gallery @KCUA. Blurring, warping, truncating, fluctuating. That black and white video footage on the monitor embodies the indeterminate, ungraspable, uncontrollable strength of women, fair yet forceful.

Performance of Reanimation in Celebration of Kyoto Prize Laureate Joan Jonas, Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

Performance of Reanimation in Celebration of Kyoto Prize Laureate Joan Jonas, Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

Performance of Reanimation in Celebration of Kyoto Prize Laureate Joan Jonas, Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

Performance of Reanimation in Celebration of Kyoto Prize Laureate Joan Jonas, Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

Jonas’s fascination with water has perhaps the same origin. In Reanimation, for instance, not only is footage of the sea surface and streams frequently projected onto the screen, Jonas also soaks melting ice cubes in Indian ink and draws patterns by hand on cardboard. And in the recent video work Moving off the Land II (2019), another exhibit at @KCUA, sandy beaches and the ecology of marine life filmed in the sea off Jamaica are conveyed to us not through the formal language of adults, but rather in the falteringly uttered words of the children who symbolize the future.

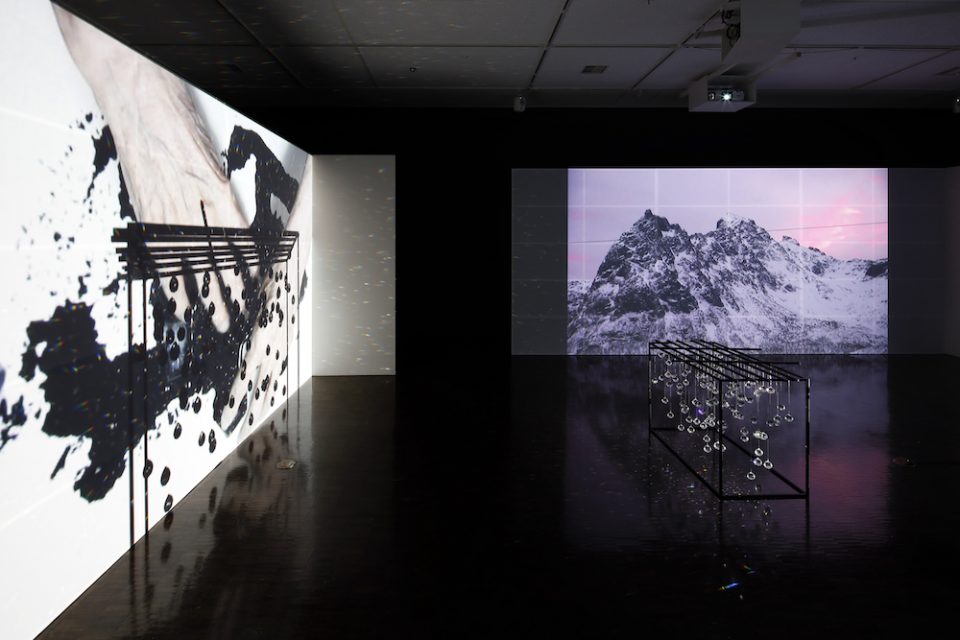

In contrast to the stationary nature of land, water is mutable. Attempting to visualize that indeterminate form of matter just as it is, onto the screen are superimposed various images like ripples appearing and disappearing: fish, children, Jonas diving or reading poetry and prose, her pet dog playing among the waves, surf cleaning a sandy beach, wave crests visible on the horizon. Or by implying the providence of the natural world whereby all kinds of things exist interdependently and in mutual cooperation, she evinces a previously unseen constellation of relationality in the exhibition room. Her work naturally evokes such philosophical posthumanist notions as Bruno Latour’s actant and Jean Bennett’s vibrant matter.

During my time in New York in 2018, I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to view the work of American artists from the same generation as Jonas such as Trisha Brown, Meredith Monk, Richard Serra, ORLAN, and (shortly before her death) Carolee Schneemann, though each time, to speak candidly, their work felt like the task of confirming the “past exploits” of a legendary artist, and never like contemporary art responding vividly to our rapidly changing society today. And it is for this reason that what left an impression, more than anything, when seeing this work by Jonas was her stance, whereby she references her past methodologies while striving to respond sincerely to the present day and create an entirely new kind of work. This is a light-footed attitude of returning once again to revise an artistic language with which one had previous success, to not cling to the past. In a text written for the Joan Jonas retrospective at Queens Museum (2003–2004), DJ Spooky describes the work of Jonas as a shared quest for developing “new vocabularies” that implicates both performer and viewer in order to reconfigure “new stories from the old.” (1) Leading and enjoying this adventure is the 83-year-old Joan Jonas.

In the final scene of Reanimation, Jonas walked straight over to the piano stage right, taking the hand of Moran while he was still playing and pulling him to the center of the stage to take their bow together and end the performance. Our time alive does not have a beautiful beginning or ending like in a story. That everything is all too “midway” was plainly expressed in what Jonas did. And this clean ending also seemed to express the very way that Jonas treats life.

(Translated from the Japanese by William Andrews.)

1. Jane Philbrick, “(Re)viewing ‘Lines in the Sand’ and Other Key Works of Joan Jonas,”, PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, Vol. 26, No. 3, September 2004, pp. 17–-29.

Photo: Takeru Koroda, Cortesy: Kyoto City University of Arts

Photo: Takeru Koroda, Cortesy: Kyoto City University of Arts

Photo: Takeru Koroda, Cortesy: Kyoto City University of Arts

Photo: Takeru Koroda, Cortesy: Kyoto City University of Arts

Performance of Reanimation in Celebration of Kyoto Prize Laureate Joan Jonas

12 DEC 2019

ROHM Theatre Kyoto South Hall

https://rohmtheatrekyoto.jp/en/event/55153/

Joan Jonas, Five Rooms For Kyoto: 1972-2019

14 DEC 2019 – 2 FEB 2020

Kyoto City University of Arts Art Gallery @KCUA

https://gallery.kcua.ac.jp/en/

Joan Jonas | Celebration of Kyoto Prize Laureate | Special Website:https://gallery.kcua.ac.jp/joanjonas/?lang=en

Kyoko Iwaki is a JSPS Post-Doctoral researcher affiliated with Waseda University. Currently, she is also a part-time lecturer at Chuo University. Kyoko obtained a PhD in Theatre from Goldsmiths, University of London in 2017. After her completion of PhD, she became a Visiting Scholar at The Segal Center, The City University of New York. Her publications include, Japanese Theatre Today: Theatrical Imaginations of Eight Contemporary Practitioners (Tokyo: Film Art Publishing, 2018 in Japanese). She has also contributed a chapter (chapters) to Fukushima and the Arts: Negotiating Nuclear Disaster (London, Routledge, 2016) and A History of Japanese Theatre (Cambridge University Press, 2016) among others. From September 2020, she is a Lecturer of Theatre Studies in University of Antwerp.