A Bar-Hopping Lesson in Architectural Reality

For the better part of three years now I’ve been traveling around Japan reporting on “snack” drinking establishments by the name of Limelight, as part of a series for the photographic monthly Asahi Camera. And I must confess, visiting some 30 bars named “Snack Limelight” in locations from a Hokkaido fishing village in the north to drinking dens on tropical Yonaguni island in the far south has been a blast.

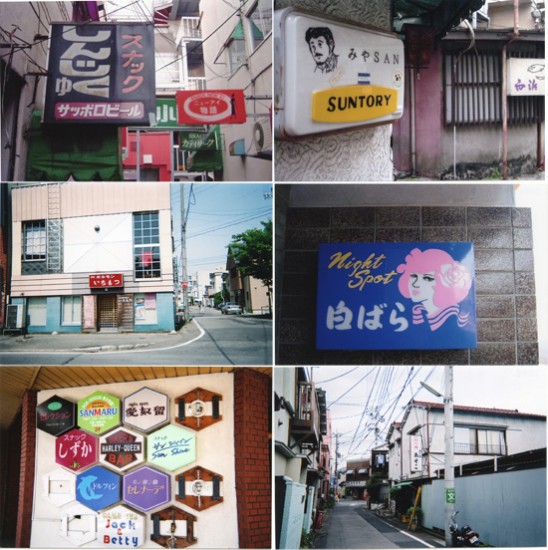

Of the estimated 150-160,000 snacks in Japan, why focus on “Limelight”? Because it’s been suggested that there are more bars in Japan by this name than any other. Not that there’s any “national snack association” to confirm this, but even a cursory glance at phone books and on the Internet reveals at least 70 such-named establishments scattered across the country. What is surprising is that the name Limelight is also favored by various other businesses, from Chinese restaurants to brothels and even, unusually, a dry cleaner’s. The name is written in Chinese characters that literally mean “coming dream, coming person,” and are read “rai-mu-rai-to.” Its sheer popularity shows how skillfully this ultra-minimalist verse of just four characters and unknown authorship speaks to the Japanese soul – in a vein similar to the ubiquitous bosozoku bike-gang tag “night-dew, death-torment,” which is read “yo-ro-shi-ku” and provocatively puns the homophonic Japanese salutation used to express regards to another person.

Every month I make my way to a “Limelight” in a different prefecture, taking photos and conducting interviews. I talk to the proprietors – Mama-san or Master – about all manner of topics, but the one question I invariably pose is, “Why did you choose the name Limelight?” One proprietor cited a love of Chaplin films, another Rumiko Koyanagi’s “Limelight” (a middling pop hit from 1980). But I was rather surprised to find that the most common reasons are, “It is a name you hear a lot” and, “A customer saw it somewhere and recommended it.”

It is unlikely that any one person would run many more than one drinking establishment in a lifetime. Comparing the bar trade to my own, that of an editor, I suppose at most a proprietor might establish a new bar about as many times as I’d launch a new magazine. In fact, as life events go the former might be even more rare. Now were I to start a new magazine, I’d think long and hard about the name: something no one else was using, something unique – like ART iT, for example. I have long imagined owning a bar to be exactly the same. However, rather than adopting a name that no one else would ever think to use, a new proprietor might instead seek the most common name possible. That whole philosophy of life – if it’s not overly dramatic to put it that way – perfectly captures the essence of the snack as a laidback pleasure spot. Here we have a way of living neither in the past nor in the future, but firmly in the present, where making a snap decision about something of once-in-a-lifetime importance is no big deal. This laxity, or lack of complexity, is precisely what makes owning a snack so alluring. Ultimately, this nonchalant attitude is what I find so seductive about the lives of snack owners.

Every few months a fat envelope turns up at my address. Inside are snapshots of bar districts around Japan, the sender one Junichi Hirata, born 1970. A Kawasaki native, Hirata took a job as a machinist after graduating from his local high school. At the same time, he started recording music by himself on multi-track cassette tapes and, on weekends, traveling around Japan on Seishun 18 discount local-rail passes. In 1993 he released his first CD, God Save the Raji-kase Rock, and continues today to present unique live performances, including those at a well-known venue in Tokyo’s Koenji district, serenading audiences with poetic lyrics while banging on confectionery tins to backing tracks recorded on a small radio-cassette player.

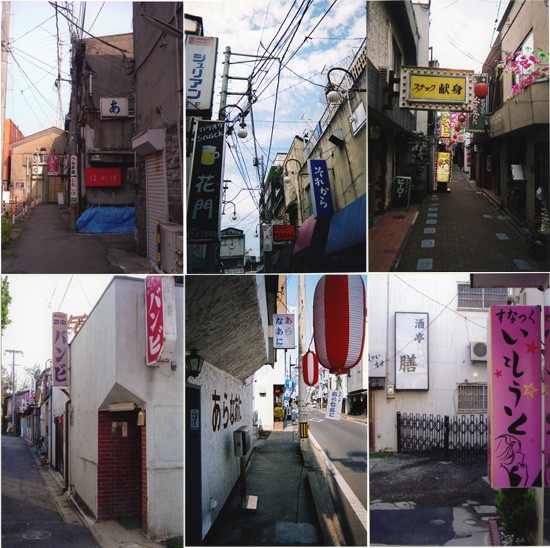

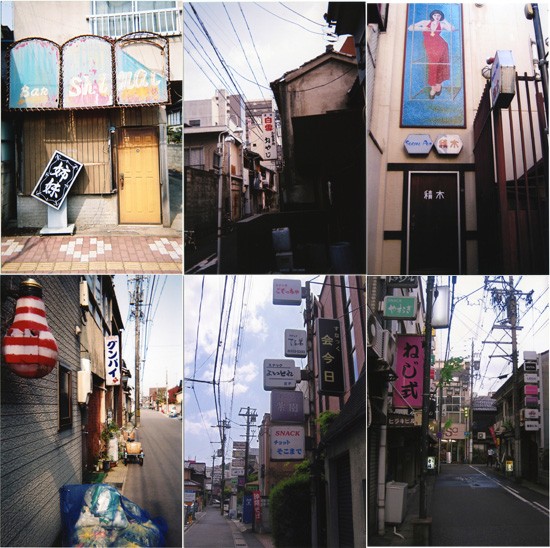

Hirata says he began photographing snacks in 2000. On a trip to the city of Shin-minato (now Imizu) in Toyama, he was impressed by scenes he encountered there of local trains and the entertainment district. Having no camera on him at the time, he photographed these scenes using a disposable model. From then on he was hooked, and embarked on an exhaustive survey of Japan’s regional cities.

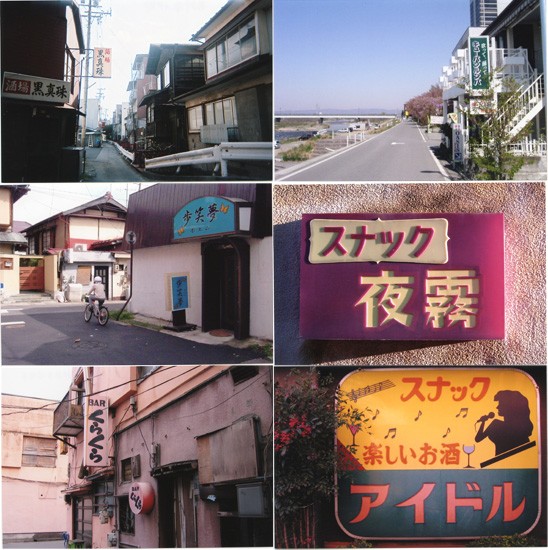

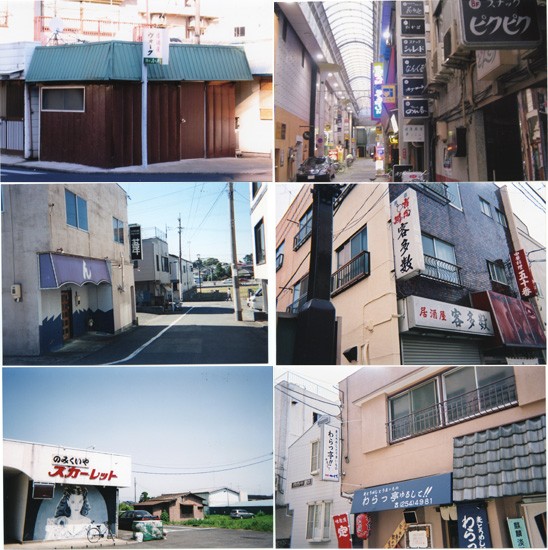

Hirata photographs bar districts during daylight hours – totally deserted precincts peculiar to the less populated corners of the archipelago; bar signs showing names into which only minimal, if any, thought has been applied; gaudy façades; rundown booze joints ripe for the wrecking ball; weary, old faces that the dark will conceal once night falls, but are unable to hide from the harsh glare of daylight. As I laughed at the bizarre names of the bars in these photos, and the frightful design sense of the signage, it gradually dawned on me that here was actually a kind of seedy poetry. Here was the reality of Japan in 2010. And while it may not be remotely cool, or trendy, that reality can – depending on your point of view – be quite delightful, and far from unpleasant.

Japan’s architecture media congregate in Tokyo, but the main outlet for Japanese architectural talent right now is in the regions, in towering station buildings surrounded by shuttered small-town shopping arcades, in the magnificent shells of government offices and art museums that only impress on the outside. Flip through any architecture magazine and you’ll find it crammed with “works” of this nature, but the reality of being Japanese, right here right now, and of living somewhere other than Tokyo, as 90 percent of us do, will never be found in “architecture as art” such as this. So-called cutting-edge architects simply cannot see how ridiculous it is to discard the local for a stab at something global even when the buildings are made for people who are perfectly happy to remain local.

I now have several hundred 3×5 prints sent by Hirata. I’d love to turn them into a book one day, but the man himself persists in demurring with an embarrassed smile. Doing temp work to get by, he continues to spend his off-days walking alone around Japan’s bar districts in the blazing sun, documenting them for posterity.

While I no longer expect anything from big names at the top of the heap, it would be wonderful if even one in a 100 aspiring young architects forsook that pilgrimage to Europe in pursuit of Le Corbusier, Mies, et al, to sweat it out stumping around the rundown bar districts on their own turf where people can, with a straight face, name their establishments things like Limelight, Cactus/Kakutasu (Lots of customers) and Madonna /Mado-onna (Bewitching woman).

Because no matter how you dress it up or how you stretch the truth, architecture devoid of reality is architecture without love, either.

All photos Junichi Hirata.