The lost world of the radio cassette player

HITACHI TRK-W4U, (ca.1984), 50 x 15 cm

Whenever a story like “Pakistanis collect stolen cars to secretly ship offshore” or “Bulk bicycles found bound for North Korea on the Mangyongbong-92” hits the news, invariably there is mention of a “yard” – a temporary holding pen of sorts, surrounded by a high fence and located deep in the hills or in a corner of some fallow field, where cars, bicycles, household appliances and so on are gathered to send overseas.

At these yards, frequented by buyers hailing from the Middle East to Southeast Asia and most points in between, word has it the most popular electrical appliances destined for new lives in the developing world are not – as one might expect – TVs or refrigerators, but humble radio cassette players, or “raji-kase” as they are known in Japan. Their ability to run on batteries makes them ideal for listening to the radio in places without power. Batteries will last around a month if the machine is used solely to tune into music, news etc. on the radio, making it a vital means of staying connected with the outside world.

In places like Thailand and Vietnam one spots street stalls with piles of cassettes stacked alongside CDs. Even music shops in America and Europe still sell new tracks on cassette as well as compact disk. If you’re reading this website it’s likely you don’t even bother with CDs any more, instead just downloading the music you want, but even in Japan cassette tapes still have an important role to play: in the realms of enka and karaoke. Go to any record shop specializing in enka and you’ll still find tapes on sale alongside CDs, not to mention piles of blank tapes for recording.

Record store proprietors explain that a CD player is next to useless for that “rewind a bar and try again” variety of fine-tuning people do when practicing karaoke, and older customers in particular prefer cassettes. Certainly it’s true that in terms of interface operability, the good old analog cassette deck beats even today’s flashiest CD players, MP3 players and so on hands down. Moreover if the data on a CD or MP3 is damaged in even just one place, the whole thing becomes unreadable, but with a cassette, you can just rejoin the affected part to play the remaining data undamaged. And as a memory device too, the tape is a far more stable medium than hard disk or CD.

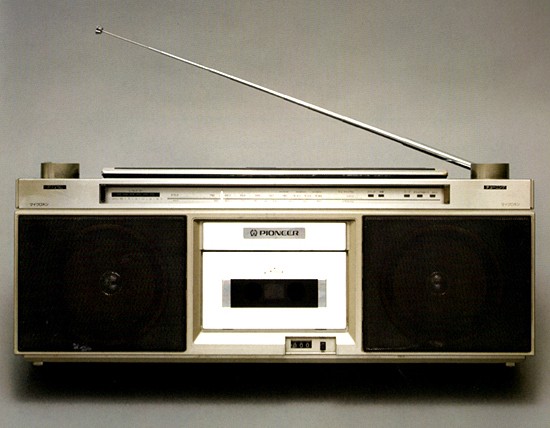

PIONEER SK-400 (RUNAWAY MIDI), (1980), 50 x 20 cm

To listen to these cassette tapes you need a radio cassette player – that wonderful invention that emerged from Japan in the late 1960s. Incidentally, the term “radio cassette player” is said to have been coined by Pioneer, also makers of the world’s first commercial car stereos, car navigation systems and laser disks.

The raji-kase, with which one can listen to the radio, play cassettes and record, and which runs even on AC power and batteries, was a revolutionary technology that enabled music previously confined indoors to step outside and get on the move. Probably more revolutionary than the Walkman or the laptop, and definitely a greater innovation than the iPod.

Those of a certain vintage will remember the much-loved “boom boxes” and “ghetto blasters” that underpinned the early development of hip-hop in 1980s America. Taking music out onto the street, carrying around one’s own personal sound system: without the radio cassette player to make this possible, hip-hop culture may never have been born.

And the radio cassette decks that took the world by storm from the 1970s to the early ’80s were almost without exception made in Japan. In the South Bronx black youths strutted around with Japanese cassette players on their shoulders, while in Beijing, the Chinese nomenklatura in their apartments danced close to mood music emanating from those very same decks.

Since then the radio cassette player has fallen from favor, its role reduced to that of “poor man’s audio” for the technophobic or those without access to newer technology – that is, those unable to either purchase or use CDs or MP3s – leaving only a handful of childish, ugly specimens lurking in dusty corners of electrical stores. A sad and sorry fate for the once all-conquering raji-kase.

Left: SONY CFM-11 (Musican), (1981), 16.5 x 24 cm. Right: SHARP CT-6001 (Color TV THE SEARCHER), (1980), 59 x 35.5 cm

There are many who look back fondly on the robust, redoubtable players that enjoyed global domination in the 1970s and ’80s. In fact, obsessive collectors of radio cassette decks abound in Asia and the West, with parts for repairs also much easier to find outside of Japan.

Like cars, household appliances have now become black boxes, meaning that when something breaks, it’s no longer a matter of repair, but replacement. In the case of the cassette deck however, you can see the tape turning, and the mechanism and internal wiring are all visible. Thus “mechanical” in nature, the trusty raji-kase is eminently fixable. Which in turn, for some, makes it very attractive. While it’s hard to imagine still repairing and continuing to use your iPod thirty years hence, with a radio cassette player, it’s perfectly feasible.

The radio cassette player is laughably large and heavy compared to today’s music devices. This is also partly what makes the raji-kase sound so great. It also functions as a stylish retro chic design object. And you can record sound easily yourself using cassettes. No matter where you go in the world, the CDs sold in stores are packaged music, a commercial product, but flea markets and other less orthodox outlets frequently offer untidy heaps of odd tapes that on listening may turn out to be just talking, or a message of some sort, or even sounds from nature; all recorded directly, without mixing or modification. Or, one of those very personal homemade compilations with a list of tracks handwritten in small print on the cover. That intimate quality, that sense of the creator, is something very specific to the cassette tape.

These days, even if one happens to find a cool-looking radio cassette player in a second-hand shop perhaps, or at a flea market, the odds are it won’t actually work properly. And it’s not as if you can take it to the manufacturer’s agent for repair. I’m sure many of us have had the experience of finding one of these treasures and thinking “hmmm, I really want it, but…no point having it just for decoration.” Recently however, fans of radio cassette players from that golden era of the ’70s and ’80s have been opening their own repair and resale outlets. Tokyo’s Design Underground in Adachi-ku, shown here, is a private workshop at the forefront of a trend toward a renewed appreciation of the radio cassette player.

Japan may just well be the best country in the world at creating things and then discarding them with no understanding of their true worth – the lost culture of the radio cassette player being yet another unfortunate casualty.

Design Underground, with a workshop located in a public housing complex in Hanabatake, Adachi-ku, is one of a rare breed: a factory where old raji-kase are given a new lease of life. It is the brainchild and gamble of an interior designer so smitten with ancient radio cassette players that when he was already in his 40s he quit his job to devote the rest of his working days to them.

Design Underground is situated in the ground-floor shopping precinct of a rundown, dated cluster of housing blocks in the north of Adachi-ku bordering on Saitama, stretching between the rather inaptly named Hanabatake – meaning flower garden – and Hokima.

Pushing open the opaque glass door of the one place in this little shopping center that actually seems to be open during working hours on weekdays, one is greeted by the chaotic sight of radio cassette players, portable TVs, parts, parts and more parts, piled all over the place. A tentative hello directed toward the back of the shop, screened from view by shelves, summons Junichi Matsuzaki, boss and self-styled “factory foreman” of Design Underground.

Born in 1960, Matsuzaki has recently presented his own personal collection of radio cassette players in an exhibition titled “Raji-kase Design!” and has also published a photo collection-cum-confession showing his extraordinary passion for the machines. The players here are just a sample of some of the stellar specimens resurrected by his devoted hands.

Design Underground

Hokima No. 5 Danchi 14-105, 5-15 Minami Hanabatake, Adachi-ku, Tokyo

All images from Junichi Matsuzaki’s Japanese Old Boombox Design Catalog (2009), courtesy Seigensha Ltd.