Madhat Kakei’s paintings, wanderings/circles, and coincidence

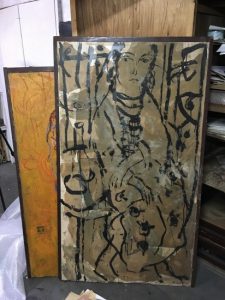

Installation view of untitled paintings by Madhat Kakei at Akutsu Gallery, Maebashi (2017). All photos: Noi Sawaragi, courtesy Madhat Kakei.

A young architect friend told me there was a Kurdish painter with a solo exhibition underway in Maebashi. His name was Madhat Kakei. “Kakei” sounds like a Japanese name, but the artist has no Japanese blood. Apparently it’s a common name among Kurds who have religious beliefs descended from Zoroastrianism (it seems the artist used to go by the Arabic name Madhat Muhammad Ali). Zoroastrianism is closely connected to the worship of fire, so much so that its adherents are sometimes referred to as “fire worshipers,” and one could if one wanted to write the name “Kakei” in Japanese using the characters for “fire” and “system.” Of course, this is nothing more than coincidental nonsense. But it is also a coincidence that Kakei came to Japan through a connection with a Japanese friend he met in Madrid. Since then he has travelled back and forth between Japan and Europe, and has maintained for some time now a space at Shosei-kan, an atmospheric joint studio housed in a refurbished old medical clinic in a lushly green neighborhood on the outskirts of Chiba city. But Japan is not his sole base. Kakei also has studios in Stockholm and on the outskirts of Paris, meaning there are three locations around the world where he is able to pursue his artistic practice. No doubt this is not particularly unusual in today’s globalized world. But in Kakei’s case, the circumstances are somewhat out of the ordinary.

Born in 1954, Kakei’s ancestral home is the large mountainous region in northern Iraq known as Kurdistan, not a “country” in the modern sense of the word but a de facto “homeland” for many Kurdish people over the centuries. Because parts of not only Iraq, but Turkey, Iran, Syria and Armenia are also referred to as Kurdistan, the entire region has a serious and complex multiethnic background, and has long confronted problems arising from the framework of the modern nation-state and the drawing of national boundaries. (A little further north is Georgia, where Stalin was born, also reputed to be the original source of the wine that later stood in for the “blood” of Christ. Come to think of it, Kakei’s moustache calls to mind Stalin, while his overall appearance calls to mind Nietzsche, who famously wrote a fictitious account of the travels of Zoroaster (Zarathustra) with a strong anti-Christian message.)

Madhat Kakei

In particular, because Kirkuk in northern Iraq where Kakei was born is one of that country’s leading oil producing regions, Kurdistan is in a complicated position geopolitically. It is also famous as the site of a massacre by Saddam Hussein of opposition forces using chemical weapons. It is for this reason that when the US military succeeded in removing Hussein in the Iraq War, the move towards Kurdish independence gathered momentum, as a result of which Iraqi Kurdistan is now an autonomous region with its own regional government. On September 25 last year, a referendum was held in which an overwhelming majority of more than 90 percent of voters cast in favor of independence. However, the Iraqi government refused to recognize the result, claiming it deviated from the framework of the Iraqi constitution, and neighboring countries also reacted cautiously. The difficult situation is further exacerbated by the involvement of various governments and the Kurdistan Regional Government in the conflict against ISIS, with tensions expected to continue to rise. (1)

As the above suggests, one could easily fill an entire column with the historical background of the Kurdish people. This is Kakei’s ethnic background, a background with roots in such a vast area and so time-honored it cannot be contained within a modern framework. Moreover, although he went to art school in Madrid after studying art in Baghdad, after he returned home in the 1980s the Iran-Iraq War broke out and he was forced to take up arms as a member of the Iraqi Army. Because the main theater of war extended over the area inhabited by the Kurds, in many cases the Kurds ended up fighting among themselves as soldiers in the armies of both countries. Unable to put up with members of the same ethnic group that had lived in the region since long before “Iran” and “Iraq” even existed killing each other because of a framework that had been put in place in modern times, Kakei decided to desert. He hid in the mountainous border region before making his way from Iran to the Balkan Peninsula and from there to Sweden, which was willingly accepting refugees from Eastern Europe. Sweden became Kakei’s temporary country of residence in place of his homeland. So is Kakei a refugee, an exile or a cosmopolitan? It is not clear. Because such labels themselves are no more than products of modern times. And given that Kakei has studios in three locations around the world, it is of no real consequence.

The first critics to pay any real attention to Kakei in Japan were Ichiro Hariu and Toru Sunouchi. Both men are among the small number of pioneering art critics who influenced me greatly. Incidentally, last year the architect Arata Isozaki published an intriguing essay titled “<i>Ararato-san</i>” (Mount Ararat) in the magazine <i>Kindai shiso</i> (<i>Shin rensai: gareki no mirai</i> (New series: the future of debris), Part 1, August 2017) in which he described his “wanderings” during a visit to Kurdistan to begin work on designing a contemporary art museum for the Kurds at the request of Kakei, at the beginning of which he writes that it was Hariu who introduced him to Kakei after the Iraq War. Meanwhile, the September 1987 issue of <i>Geijutsu shincho</i> I have in front of me now features Kakei as the last painter Sunouchi introducedin his series of essays “Kimagure bijutsukan” (Whimsical art museum) (Part. 163: “Goshoku no koyo” (The uses of misprints)). The solo exhibition at Formes Gallery for which Hariu contributed the essay “The Prints of Madhat Muhammad Ali” was held in November 1988, which means that both Sunouchi and Hariu became interested in Kakei in quick succession following his arrival in Japan in 1986. The names Ichiro Hariu, Toru Sunouchi and Arata Isozaki (in the aforementioned essay, Isozaki touches on the Genesis flood story concerning Mount Ararat, which is claimed to be the resting place of Noah’s Ark, while in my book Shinbijutsuron (Earthquakes in art) I devote a chapter to the legend of Uryujima, according to which Isozaki’s ancestors were swept into Beppu Bay when the island was destroyed by a tsunami) suggest that in a sense it was no coincidence that, as noted at the beginning of this column, it was through the introduction of a young architect friend, linked also to Isozaki, that I came to know about Kakei and visited the small gallery in Maebashi.

I visited the gallery near Maebashi Station on the same day that I went to see “Flap-flop, Clap-clop: A Place Where Words Are Born” at Arts Maebashi and the Maebashi City Museum of Literature. At the time, I was thinking about places (non-places) where Japanese (meaning) and images (meaninglessness) intersect. It was the final day of the exhibition, Kakei’s sixth at the gallery. As soon as I entered the gallery I saw a man whom I immediately identified as Kakei. And as I viewed the paintings we naturally began to converse. Though his English is not fluent, Kakei is talkative. After a while he produced the texts Hariu and Sunouchi had provided and showed them to me. Sunouchi had apparently visited Kakei’s studio in Chiba, since there was also a photo taken while he was there (I had no idea at the time that the next month, again just in time, as it was the day before Kakei returned to Stockholm, I would make my way to the same studio that Sunouchi had visited). We also talked about Isozaki’s essay. At which point Kakei also showed me a photo of the planned construction site for the contemporary art museum for the Kurds that Isozaki mentioned he had visited. The parched earth seemed to extend forever. I would never have thought that this was on the way to Mount Ararat, which supposedly survived the flood described in Genesis that engulfed the entire earth, in an area thought to have been completely submerged.

Only now do we come to the crux of this column: Kakei’s artworks. Such is the complicated and inscrutable nature of the circumstances surrounding the artist. But this multilayered background, so complex it cannot easily be unraveled, undoubtedly casts a large shadow over Kakei’s paintings. Viewed at a glance from in front or in printed form, Kakei’s paintings look like the kind of monochromatic paintings one might come across anywhere. However, looking closely at the real things, one can clearly see that this impression is simply the result of the brain bundling together as meaning (color) the almost indeterminate stochastic effect of the seemingly innumerable pale color tones radiating from the canvas and reaching the eye (meaninglessness). What is behind this effect in which one’s field of vision seems to fluctuate endlessly? Looking at the edge of one of the paintings, I discovered the answer. What appeared to be a monochromatic surface in fact had a cross section composed of layer upon layer of thickly applied paint, which I had been looking through in a perpendicular direction.

This method itself is far removed from the black and white woodblock prints and highly improvised fusuma paintings that Kakei was working on at the time and that Sunouchi touched on in his “Whimsical art museum” essay, and looking at the bilingual booklet produced at the time of Kakei’s 1998 solo exhibition at Gallery K in Ginza (which was also held at Maebashi, Chiba, Kagoshima, Copenhagen and Stockholm) to which Hariu contributed (and in which the famous Syrian poet Adunis paid homage to Kakei’s painting!), while the works have the same monochromatic quality, the color tones are completely different from those he uses now. Kakei’s current paintings have a vivid, almost shining quality that produces an after-effect that remains on the viewer’s retinas for a long time, like the afterimage that results from looking at the sun. The unexpected intermixing of the different layers of color applied one on top of the other (ie, past) creates a surface (ie, present) that at a glance appears homogenous. It goes without saying that this corresponds physically to the coexistence between endless wandering and the return to one’s roots that characterizes Kakei’s own journey from the past to the future, a journey that plays out endlessly between the individual and the ethnic group.

Both: At Kakei’s studio inside the Shoseikan in Chiba.

As I was about to leave the Shoseikan, our conversation once again turned to Sunouchi. I told Kakei, “Earlier this year, the art critic Hiroshi Okura, who was close to Sunouchi in his later years, took me to the site of the small mountain retreat in Niigata where Sunouchi said he wanted to spend his dying days to see if it was still there.” Kakei danced up and down with joy and said, “I’ve been there too!” At the time of my visit, the mountain retreat was buried in one corner of a slope with weeds growing all around it to above our waists, so that even from nearby we couldn’t see it. But after taking a roundabout route and scrambling up the slope we were able to reach the location. And then we saw it. Though dilapidated due to the effects of wind and rain, Sunouchi’s “final abode,” a dwelling that suited him perfectly, still survived. On hearing this, Kakei smiled as if he was truly delighted and shook my hand firmly. Then I remembered. Kakei was the “final” painter Sunouchi introduced in his “whimsical art museum.” Come to think of it, accompanying me on that strange journey to Sunouchi’s final abode was not only Okura but Hatoko Takahashi, who was visiting Niigata from Beppu. Takahashi had learned of another artist introduced in Sunouchi’s “whimsical art museum,” Kei Sato, and begun collecting his artworks. She even went as far as opening a museum dedicated to him in Yufuin, but it ran into financial difficulties and she was forced to close it. I met her by chance just before the museum closed during a trip to Beppu. She had made the journey from Niigata to attend a talk I was giving in conjunction with an exhibition on filmmaker Makoto Sato at the Sakyukan in Niigata. Sato was another individual who read Sunouchi’s art criticism and was so strongly affected by it that there was no going back. Though I had the pleasure of interacting closely with Hariu in his later years, I never got to meet Sunouchi. But his criticism rises from the dead again and again. Connecting Kurdistan and Chiba and Niigata with new ties while giving birth to unexpected coincidences and inevitabilities far and wide, just like Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence.

”Madhat Kakei” was held from November 18 through 26, 2017, at Akutsu Gallery in Maebashi.

1. “What’s next for Kurds? Iraq refuses referendum vote, wants its oil and airports back,” Newsweek, September 27, 2017. http://www.newsweek.com/whats-next-kurds-iraq-vote-wants-oil-allies-iran-syria-turkey-672647