A mountain-like inquiry into “restoration”: Yamagata Biennale 2018 (Part 2)

Works by Genkichi Takahashi featured in “Contemporary Yamagata Thought” (a special exhibit at Yamagata Biennale 2018: “100 Stories Like a Mountain”). From left to right: Tachiyagawa river v. rock face, Panoramic view of the Yamadera (both shown at the “Yamadera Oil Painting Exhibition” in 1911; collection of Shogimura Tendo Tower) and Tiger (collection of the Tendo City Araya Elementary School). All: 1911, oil on canvas. All photos: Isao Negishi, courtesy Tohoku University of Art and Design.

Works by Genkichi Takahashi featured in “Contemporary Yamagata Thought” (a special exhibit at Yamagata Biennale 2018: “100 Stories Like a Mountain”). From left to right: Tachiyagawa river v. rock face, Panoramic view of the Yamadera (both shown at the “Yamadera Oil Painting Exhibition” in 1911; collection of Shogimura Tendo Tower) and Tiger (collection of the Tendo City Araya Elementary School). All: 1911, oil on canvas. All photos: Isao Negishi, courtesy Tohoku University of Art and Design.

Some of the exhibits at this year’s Yamagata Biennale also presented fresh findings concerning Japanese modern art with “restoration” serving as a medium. I am referring to the exhibits concerning Genkichi Takahashi, the son of Yuichi Takahashi, who is known as one of the leading exponents of modern oil painting in the Meiji period, and Taketaro Shinkai, who also made an important contribution in the field of sculpture also In the Meiji period. In both cases, there was an emphasis on their reinterpreted native land based on (Junzo Ishiko-esque) criticism of modernization, as well as on their art historical significance: the existence of each of these two men, which had been obscured on account of their distance from the “center,” being newly discovered and visualized by way of Yamagata.

I will come back to the individual achievements of these two men later. But first let me state that the reason such a thing was possible at Yamagata Biennale 2018 – and this also relates to my decision to focus in this column on the question posed by Natsunosuke Mise, the artist behind the “Contemporary Yamagata Thought” exhibition, “Is restoration possible?” – can also be glimpsed from the name of the institution responsible for hosting the biennale, Tohoku University of Art and Design. Through the Institute of Conservation of Cultural Property, which was established in 2001 from the point of view of “art and design,” the university has been involved in investigation, restoration and conservation work. However, the focus is not on technology alone. Because earlier, in 1999, the Tohoku Cultural Research Center was established at Tohoku University of Art and Design, as a result of which conservation and restoration work has also taken on folkloric, cultural anthropological and local historical meaning. In fact, at this exhibition, these two centers themselves are counted among the “exhibitors” of the 38th and 36th “stories” of “100 Stories Like a Mountain” and assisted greatly in the abovementioned “discovery” and “visualization.” Let us now take a more detailed look. (1)

Consider, for example, the 42nd “story” in this exhibit, “Yuichi Takahashi: Governor Mishima’s Road Maintenance Memorial Picture Album.” Governor Mishima refers to Michitsune Mishima, the first governor of Yamagata prefecture. In 1884, Mishima commissioned Yuichi to produce a series of paintings to record for posterity the road developments he completed in Yamagata, Fukushima and Tochigi, which he regarded as important projects. At the time, Yuichi was said to have spent around four months doing research on these developments, but it was his son, Genkichi, who was largely responsible for completing the three picture albums the following year based on Yuichi’s sketches. Incidentally, such “pictorial records of public works” themselves had special significance in the new order of the Meiji period. Because in order for the newly installed government to push ahead with its plan to encourage the growth of new industry, it needed to establish a national distribution network that completely reformed the outdated feudal system of the shogunate and domains, and what underpinned this was above all the kind of centralized infrastructure development represented by roads. In order to make the abolition of the feudal domains and the establishment of prefectures a reality, too, it was also necessary at all costs to publicize these public works projects that were transforming (modernizing) the landscape in these regions through liberal application of the latest technology introduced from the West following the opening of the country to the outside world. This being the case, the picture albums also served as effective propaganda designed to convey the results of these projects to later generations. In a manner of speaking, through his work as a painter, Yuichi involved himself in an aspect of national policy.

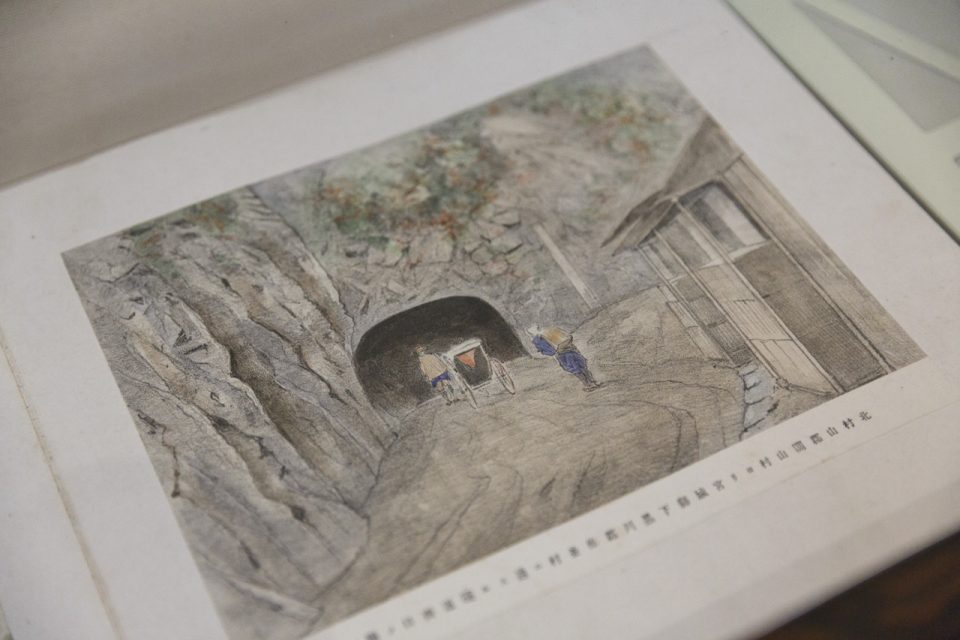

Governor Mishima’s Road Maintenance Memorial Picture Album (1885), lithography and light color on silk. Collection of Yamagata University Museum.

Governor Mishima’s Road Maintenance Memorial Picture Album (1885), lithography and light color on silk. Collection of Yamagata University Museum.

It would seem that Genkichi, also a painter, saw through this to a greater extent than Yuichi. Because while Genkichi learned the basics of painting from Yuichi, he also studied the subject at modern Japan’s first government-established art school, the School of Arts and Technology. As the name of this institution suggests, at the time the modernization of drawing was significant for the state from an engineering perspective because it would enable it to conduct the surveys and develop the strategies required to wage war with the great powers. However, with greater emphasis being placed on the function nationalism served with respect to the nation state, the School of Arts and Technology was abolished in 1883 and the leadership role in art shifted to the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, established in 1887, where Western-style painting was eschewed and Nihonga took center stage. In response to this, in 1889 a number of artists affiliated with the School of Arts and Technology formed the Meiji Art Association, with Genkichi among its key figures. However, after 1896, when the principal positions at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts were taken up by Western-style painters who had returned from studying abroad, among them Seiki Kuroda, the Meiji Art Association quickly atrophied, and in 1901 it was forced to disband. Genkichi also severed his ties with the government-sanctioned art world and embarked on a lengthy life of itinerancy. It was around this time that he showed up in Yamagata, where he had earlier striven to convey Yuichi’s achievements as a painter to future generations.

Interestingly, at this time Genkichi was involved in efforts to reestablish a pre-Meiji Restoration cultural base blotted out by Governor Mishima’s Road Maintenance Memorial Picture Album, which Genkichi had devoted himself to and was conveyed to future generations in Yuichi’s name. These efforts are the subject of the 39th “story” in this exhibit, “Genkichi Takahashi: Yamadera Oil Painting Exhibition.” In respect to which, I will cite a passage from an essay by Shinoko Oba and Shunsuke Kobayashi (2), who in recent years have been surveying and researching in depth Genkichi Takahashi’s achievements as a painter in Yamagata.

The various settlements that existed in Yamadera up until the early Meiji period had as their economic foundation the flow of people and goods along the Futakuchi Kaido, but with Michitsune Mishima’s assumption of the position of governor of Yamagata prefecture in 1876 and the completion of the Sekiyama New Road and the Kuriko Tunnel, the volume of traffic passing over the Futakuchi Pass from Yamadera, which had until then been the main route leading from Yamagata to Sendai and the Pacific coast, fell dramatically, causing them economic hardship. However, thanks to the efforts of Yamadera village, Higashimurayama district and Yamagata prefecture as a whole, the Crown Prince paid a visit to Yamadera as part of his 1908 tour of the Tohoku region, and newspapers in various places reported that the scenery at Yamadera was “more beautiful than Yabakei,” as a result of which the village’s name became widely known throughout the country. To borrow the words of Eiji Izawa, who played a central role in arranging the Crown Prince’s attendance, “Yamadera, where it seemed as if the lights had gone out, came to life again” following the Imperial visit, and went on to become a famous tourist spot. (3)

In other words, the “Yamadera Oil Painting Exhibition” played what we would refer to today as an art festival-like role in promoting the cultural aspect of Yamadera, which was placed in an unexpectedly difficult position when the flow of people and goods dramatically changed as a result of the very road projects initiated by Governor Mishima. One can appreciate from this the extent to which a single civil engineering project changed the makeup of a region and how important a role oil painting played in both “publicizing” this and “reviving” a district that had fallen into decline. The important thing is that state-of-the-art technologies of the time, including civil engineering projects and modern oil painting, have been brought back to life and reconnected in Yamagata in the context of their School of Arts and Technology origins, a context that is separate from the government-sanctioned Tokyo School of Fine Arts trajectory. In this sense, photography was undoubtedly also a state-of-the-art technology.

In the 35th “story,” “Shingaku Kikuchi: Yamagata Prefecture Photo Album,” a documentary-painting quality similar to that of Yuichi’s oil paintings can be detected in Kikuchi’s photographs, which were not only gathered together as an album but were also lurking (reiterated) in Governor Mishima’s Road Maintenance Memorial Picture Album where they provided a structural outline to Yuichi’s paintings. Genkichi almost certainly also referred liberally to photography as a form of cutting edge technology. Here, through their contiguity to “art-technology” studies, the pairing of public works and oil painting, and of oil painting and photography, form a single loop centered around the same location at around the time of modernity that transcends genre differences and value hierarchies. This is distinctly different from the Meiji art history that developed from Tokyo School of Fine Arts into the establishment of the Bunten (Ministry of Education Art Exhibition) in 1907.

Installation view of the “Osawabutsu” group of sculptures.

Installation view of the “Osawabutsu” group of sculptures.

Similarly, sculpture, too, yielded peculiar “results” in Yamagata throughout the same period. The Yamagata-born sculptor Taketaro Shinkai cultivated many successors – Teijiro Nakahara foremost among them – and is famous for the sculpture Yuami (Bathing, 1907), which is regularly displayed in collection exhibitions at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. This year is the 150th anniversary of his birth. However, as the eldest son of a sculptor of Buddhist images, he also contributed to bringing into existence the so-called “Osawabutsu,” the group of sculptures with a mysterious background that feature in the eighth “story” in this exhibit. According to the guidebook, the name “Osawabutsu” refers to a group of Shinto deities and Buddhas relating to the faith of one of the Three Mountains of Dewa, Mount Yudono. “A visit to Mount Yudono involves a practice known as ‘osawa-gake‘ in which worshippers ascend and descend mountain streams leading to the objects of worship. Over time, the names of Shinto deities and Buddhas were given to the distinctive rocks, caves and other natural objects worshippers passed along the way,” resulting in these objects also becoming objects of worship. Gradually, images and idols modeled on these objects came to be produced, actions “deemed to have the same religious merit as visiting Mount Yudono,” and these images and idols were subsequently enshrined and visited as Shinto deities and Buddhas. In fact, given these circumstances, the Osawabutsu seem to resemble beasts from the natural world as opposed to Buddhas from the heavens, and the person responsible for creating them was none other than Taketaro Shinkai’s father, Muneyoshi Shinkai, who was also a sculptor of Buddhist images. However, Taketaro apparently also helped in the making of these Osawabutsu. Although there would seem to be an infinite distance between the Osawabutsu, which can only be regarded as the product of animism, and the academic Yuami, with the insertion of the native land of Yamagata between them, they are in fact contained within an infinite gradation.

Concrete examples of this infinite gradation also take principal positions in this exhibit. These include the 21st “story,” “Taketaro Shinkai: Statue of Sho-Kannon (Aryavalokitesvara)”; the 24th, “Taketaro Shinkai: Arhat”; the 27th, “Taketaro Shinkai: Snow”; and the 17th, “Taketaro Shinkai: Siva and Parbutta.” All provide crucial viewpoints in terms of radically reevaluating the state of Japanese modern sculpture.

Taketaro Shinkai – Statue of Sho-Kannon (Aryavalokitesvara) (1925), bronze, collection of Yamagata Museum of Art.

Taketaro Shinkai – Statue of Sho-Kannon (Aryavalokitesvara) (1925), bronze, collection of Yamagata Museum of Art.

Statue of Sho-Kannon (Aryavalokitesvara), which is in the collection of the Yamagata Museum of Art, was “created by Shinkai with the aim of producing the ideal statue of Kannon” and incorporates elements from all of the sculptural forms the artist himself studied during his formative years, “including not only the forms of the Buddhist images from the Edo to early Meiji periods that he studied in his childhood, but elements of the finest statues of Kannon from the Nara to Heian periods and Indian Buddhist images.” (ibid) Arhat is one of a number of reliefs Taketaro made after returning from a trip to France and Germany to brush up on Western sculpture and was apparently “inspired by the numerous metal artworks adorned with reliefs that he saw in France.” Reliefs gradually retreated from the formative arts mainstream on account of their halfway nature, being difficult to define as either painting or sculpture, but – perhaps because the shadow cast by the local demand for decorative carving in Yamagata, one of the country’s foremost centers for the production of carved Buddhist alters – in Taketaro’s efforts to revive the art form one can get a glimpse of his peculiar way of thinking.

Taketaro Shinkai – Arhat (1908), bronze, collection of Yamagata Museum of Art.

Taketaro Shinkai – Arhat (1908), bronze, collection of Yamagata Museum of Art.

Taketaro Shinkai – Snow (1917), color on plaster (plaster cast), held by Yamagata Museum of Art.

Taketaro Shinkai – Snow (1917), color on plaster (plaster cast), held by Yamagata Museum of Art.

Snow is an “ukiyo chokoku” (genre sculpture) that Taketaro began working on in 1911 in which he “sought to depict through Western-style sculptural techniques some of the Japanese social manners and customs of the time such as shoeshining and sumo training,” and could perhaps be described as “the sculptural equivalent of ukiyoe.” But of the four works, the most remarkable is probably Siva and Parbutta. This is a plaster figure created as the mold for a bronze work, and given that very few of Taketaro’s plaster molds survive, it is extremely valuable. Astonishingly, it was apparently discovered by accident in 2014 at the Casting Department of Nishimura Kojo in Yamagata City. In combination with the 28th “story,” “Takezo Shinkai: Mother and Child” (a sculpture by Taketaro’s nephew depicting inhabitants of Yap based on photographs taken by an anthropological survey team dispatched to the islands of Micronesia occupied by Japan in World War I) and the 31st “story,” “Takezo Shinkai: Chinese Lion” (a downsized version made in bronze of the guardian dogs Takezo created for the Yamagata Prefecture Gokoku Shrine), these works shake from its very footings the view of the history of Japanese modern sculpture we vaguely remember with from history textbooks.

Left: Taketaro Shinkai – Siva and Parbutta (1915), color on plaster (plaster cast), held by Yamagata Museum of Art.

Right: Takezo Shinkai – Mother and Child (1915), color on plaster, collection of Yamagata University Museum.

Takezo Shinkai – Chinese Lion, bronze, collection of Yamagata City.

Takezo Shinkai – Chinese Lion, bronze, collection of Yamagata City.

The crucial thing is that when one actually stands in front of them, one senses that these peculiar pictures and images are in fact the normal state of the formative arts we see in the Japanese archipelago from day to day. And let us not forget that this was discovered as an extension of Mise’s question, “Is restoration possible?” It goes without saying that here, “restoration” is not limited to physical restoration but includes “restoration” (as opposed to recovery) as it pertains to the loss of memory concerning art in the Japanese archipelago. And this itself will undoubtedly become an important support when it comes to thinking about the question that Mise has positioned further up ahead: “Is the restoration of the regions possible?”

Note 1: Akira Miyamoto, co-curator (with Natsunosuke Mise) of this exhibition, runs a cultural property management company to support the restoration and preservation of local cultural assets, including the launch of Japan’s first Buddhist image crowdfunding project. The following website shows examples of restorations of the oil paintings by Genkichi Takahashi featured in this essay, restorations carried out in collaboration with Shinichi Nakane of the Yamagata Historical Building Research Society.

https://camp-fire.jp/projects/view/44552

Note 2: As indicated by the presence of the word “contemporary” in its title, one of the main purposes of this exhibit was to undertake a reinterpretation of the modern era throughout Yamagata as a whole in parallel with the contemporary, which is why a large number of works by contemporary artists were displayed. However, touching on these would have required even more installments of this column and resulted in it deviating from its original “comments on current events” nature, and so reluctantly I abandoned the idea. One could say it was a “mountain-like” exhibit that kept on giving.

Yamagata Biennale 2018 was held from September 1 to 24, at the Yamagata Prefectural Local Museum “Bunshokan” and Tohoku University of Art and Design, among other venues.

1. For details on the contents of the exhibitions discussed in this essay, see the 100 Stories Like a Mountain guidebook (editorial direction: Natsunosuke Mise) (Suginoshita Design Room + Aya Nakajima, 2018).

(https://biennale.tuad.ac.jp/2018/100mono.pdf)

2. Shinoko Oba and Shunsuke Kobayashi, “Genkichi Takahashi and Yamadera,” in A Report on the Research Results of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Private University Strategic Research Base Formation Support Project (2010-2014) “Research on preserving local cultural heritage through multifaceted preservation/restoration activities and improving regional cultural power” (Tohoku University of Art and Design, Institute for Conservation of Cultural Property, March 20, 2015), pp. 83-101. (http://www.iccp.jp/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/1.2.pdf)

3. Ibid., p.95. Note that the original gives 1976 as the year of Michitsune Mishima’s assumption of the position of governor of Yamagata prefecture; this has been corrected to 1876 in the citation.

For readers in Japan: Noi Sawaragi is scheduled to speak on December 9 on the subject of NeoPop and its times”, an episode of the talk series “Wartime Japanese Avant-garde Art” running in conjunction with the exhibition “Records of Space Plan – Totttori’s Avant-garde Artist Group” (at Birds’ Gallery Tottori). The talk will be moderated by curator of the exhibition Hiroki Tsutsui.