A mountain-like inquiry into “restoration”: Yamagata Biennale 2018 (Part 1)

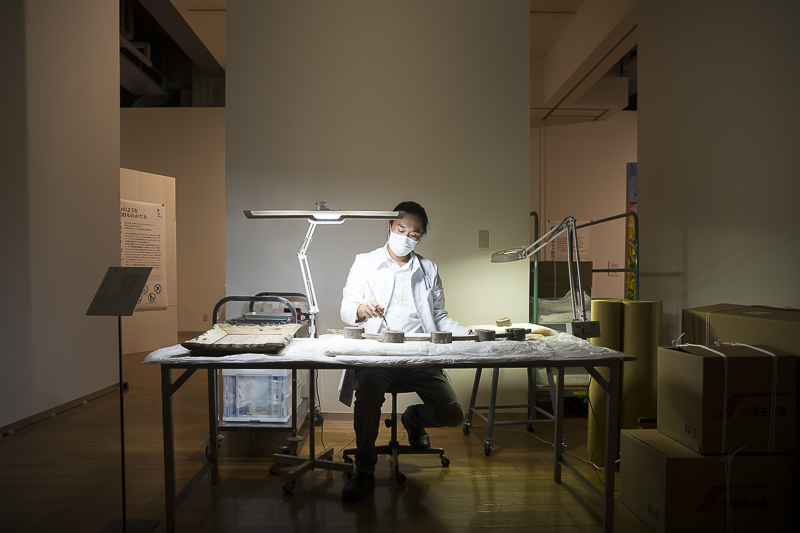

Hiroaki Ido – Haibutsu kishaku (engaging in restoration) (2018), installation view at “Contemporary Yamagata Thought,” (a special exhibit at Yamagata Biennale 2018: “100 Stories Like a Mountain.” All photos: Yamagata Biennale.

Yamagata Biennale 2018 is the third edition of the art festival that celebrates “art in the mountains.” This year I attended for the first time. As usual, it was hosted by Tohoku University of Art and Design. But the biggest difference compared to the previous two editions is probably the significant increase in the number of exhibitions staged at the vast university campus in addition to those held in venues around Yamagata Station (the Bunshokan area). In any case, the title “mountain-like” applies to the entire event. It includes such a mountain of exhibits that it was literally impossible to see them all.

While there were various highlights, perhaps the most noteworthy development at this year’s biennale is the curation by artist Natsunosuke Mise – who leads the “Is Tohoku-ga (Tohoku-style painting) possible?” project that has been ongoing at Tohoku University of Art and Design since before the March 2011 disaster – of an exhibition within the university grounds titled “100 Stories Like a Mountain,” which accounts for the majority of the space devoted to the biennale as a whole. Consequently, this year’s Yamagata Biennale far exceeds the bounds of an art festival as a project hosted by a single university and reaches a completely new level worthy of careful consideration by everyone involved in art, not only in Yamagata but throughout the Japanese archipelago. The main reason for this is that “Contemporary Yamagata Thought – Is Restoration Possible? Community/Region/Japan,” a special exhibit co-curated with cultural heritage management specialist Akira Miyamoto and presented in such a way that it uses effectively the far-from-desirable corridor-like space on the seventh floor of the main building, is almost unprecedentedly challenging from the perspective of thinking about Japanese modern art. I will expand on its significance in a later column, but here I would like to begin with a summary of its contents.

Installation view of “Contemporary Yamagata Thought.”

Resembling a “cabinet of curiosities” crammed with everything from images of deities to sculptures, ema (votive tablets) to oil paintings and mysterious plant specimens, the exhibit is divided into nine parts in accordance with Miyamoto’s classification. In order, these are “01 Mukasari ema and contemporary views of life and death,” “02 Yudono-san faith and Osawabutsu,” “03 Various manifestations of Yamagata metal casting,” “04 Buddhist images in the modern era,” “05 Modern reliefs and Yamagata,” “06 Taketaro Shinkai and the blending of Japanese and Western styles,” “07 Exploring urban landscapes,” “08 Yuichi and Genkichi Takahashi and modern Yamagata” and “09 Collecting nature.” But there is also a prelude-like introductory chapter that begins as soon as one steps out of the elevator, with the exhibits proper laid out beyond a temple gate-like display through which visitors pass. This “introduction” and “gate” subsume the entire exhibit, which is structured so that after seeing it one arrives back at the beginning. In other words, the “gate” and “introduction” that serve as the entrance turn inside out, becoming the “exit/entrance” to a newly reformed world.

At this entrance, counted as the second of the “100 stories,” we come across a man in a surgical mask concentrating on some kind of activity, the subject of which is the artwork Haibutsu kishaku (2018) by sculptor and conservator Hiroaki Ido. That being said, on “display” is the artist himself and the process of restoring ancient cultural properties with which he is involved. Together with the unusual shapes of the tools designed specifically for use in conservation work, the manner in which he shines a light on the subject on his worktable, studies the details and silently moves his hands gives the appearance of a surgeon about to commence an extremely difficult operation. The term haibutsu kishaku, of course, refers to the widespread destruction of Buddhist images that occurred all over Japan in response to the Ordinance to Separate Shinto from Buddhism, which was promulgated as part of a move at the time when Japan was beginning to modernize to follow in the footsteps of the West by establishing a form of monotheism (State Shinto) with the Emperor at the top. Readers may recall that this year is being promoted as the 150th anniversary of the Meiji Restoration, in which sense it is exactly 150 years since haibutsu kishaku. (It is also a truly intriguing coincidence (?) that next year we will witness the “previously notified” ending of the Heisei period under the present Emperor.)

Installation view of the statues of Fujin and Raijin (Oe-cho Ikazuchi Shrine) and at nimbus paintings by Tatsuaki Oyama Thunder and Lightning Nimbus, Whirlwind Nimbus at “Contemporary Yamagata Thought.”

This restoration work serves as a hidden approach to the gate (ie, bounds of a sacred place) formed up ahead by the two statues of deities. These are the statues of Fujin (the god of wind) and Raijin (the god of thunder) that from some point onwards were seemingly abandoned in the inner sanctuary of the Ikazuchi shrine at the top of a steep slope in a certain village (Oe-cho). In fact, it is no exaggeration to say that “Contemporary Yamagata Thought” began with (or rather, begins with) these two statues. Because the objects Ido is working on in the aforementioned “introduction” are a battered tablet from the torii (gate) leading to this shrine and bearing its name, the drum Raijin beats to produce thunder and the “wind bag” Fujin uses to produce wind and rain. The two statues were apparently enshrined in the main hall in the inner sanctuary beyond this torii, but they were so dilapidated that it would have been no surprise had they collapsed under the weight of the snow that would have fallen come the next winter. In a sense, this green god of wind (ie, god of water) and red god of thunder (ie, god of fire) were “saved” due to human intervention immediately prior to this – despite them being gods.

There are reasons for the “abandonment” of such local cultural properties that go back to the very haibutsu kishaku mentioned above. Because originally, statues of Fujin and Raijin were not enshrined in the main halls of Shinto shrines; rather, they were normally situated on either side of Buddhist temple gates. In this sense, too, they are special. Furthermore, the sculpting of the two statues could not really be complimented or described as skillful; rather, they almost have the appearance of imitations made by a novice (a carpenter?) following the example of others. But even so, why were such images displayed in the inner sanctuary of a Shinto shrine? Could it be a practice that has at some point naturally made a comeback here in the Japanese archipelago, where the synthesis of Buddhism and Shinto has long been regarded as a custom? Or is it that “in response to the separation of Shinto and Buddhism at the start of the Meiji period, a Buddhist image in the main hall was removed and we were shifted from our original location on either side of a Buddhist temple gate to inside the main hall”? (1)

Installation view of Osawabutsu and works by Soichiro Fukai at “Contemporary Yamagata Thought.” The exhibition features a mix of historical materials and works by contemporary artists.

The question curator Natsunosuke Mise is asking about such statues here, before all the other exhibits, is “Is restoration possible?” This is also the difficulty dealt with in a way that provides no clear “answers” in Ido’s Haibutsu kishaku, the work that serves as the “introduction” to the entire exhibit, in which the artist is seen restoring abandoned “cultural properties” he himself came across in the course of his investigation. The questions Ido poses are these. “Do artworks have a lifetime? Do they live forever as long as they are stored and conservation work continues? Are they really alive if there is no chance that they will be seen by anyone…? What ‘death’ means for art is not clear. Maybe there is even such a thing as mercy killing. Why were they made, and why are they being preserved?” (1) Perhaps this accounts for the fact that Ido’s work is somehow suggestive of surgery (ie, resuscitation). Perhaps surgeons, too, are faced with a similar question. In some cases, rather than surgically “restoring” something in the knowledge that it will not return completely to its original condition, wouldn’t it be better for it to be “euthanized” as is?

In an essay titled “Is Restoration Possible?” Mise again poses a similar question. “Where should these statues be in the future? They will be carefully restored and kept in a museum. Yet this is not where these statues should really be. But there are no longer any people waiting for them. If nothing is done, at around this time next year they will probably have been crushed by heavy snows, and will some day turn back into soil. Perhaps this in itself is a beautiful ending.” Here, a method of inquiry (is such-and-such “possible?”) characteristic of Mise, who continually asks “Is Tohoku-ga possible?” is repeated like superscript. Mise does not regard either “Tohoku-ga” or “restoration” as established in advance. Because both are things that only barely reveal themselves through the process of asking “Are they possible?” and actually practicing them. In “Contemporary Yamagata Thought,” too, while taking as his starting point such a difficult-to-answer question, Mise does not go on to assert either that restoration is meaningless because of this, or that restoration is definitely meaningful despite it. Rather, he attaches importance to slowly bringing into the open the countless “stories” that lie scattered between these two poles. Accordingly, this exhibit’s “introduction” and “gate” are a completely necessary “approach/birth canal” designed to enable each viewer to uncover by their own efforts the “(101st?) story” that emerges as a result of such questioning.

“01 Mukasari ema and contemporary views of life and death” continues directly after this demonstration of the “ambiguous” state these statues of deities find themselves in at present. The word “mukasari” originates in a dialect used in the Murayama region of Yamagata prefecture. It derives from the standard Japanese “mukaeru” (“to greet”), and has come to mean “to marry.” And ema are votive tablets. So mukasari ema are votive tablets depicting wedding scenes (mostly the exchanging of cups of sake). In Japan, votive tablets are offered during prayers to Shinto deities or Buddha for the fulfillment of a wish. In other words, the pictures on the tablets represent scenes that have been prayed for. Accordingly, mukasari ema depict the weddings of people who, due to their premature death or some other reason, were not able to marry during their lifetime, in the hope that they might at least experience marriage in the next world.

Installation view of mukasari ema at “Contemporary Yamagata Thought.” Shown beside them are what might best be called contemporary mukasari ema works by Yukiko Hata and Hiroaki Kano (bottom photo, left).

What we are able to see by way of this exhibit are recreations (ie, realizations) of such scenes (including recent examples made by combining separately taken photographs of a bride and groom or featuring victims of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami) that were not originally intended to be viewed at all. In fact, their nature is such that people with no connection to the families might normally shy away from viewing them. But using as a steppingstone the question “Is restoration possible?” he posed in regard to statues of deities, Mise dares to display them while grappling with the question “Is the artistic appreciation of ema possible?”

Such questioning of the essentially “ambiguous” nature that cultural properties inevitably have in the modern era also relates to the problems art critic Junzo Ishiko faced when he, too, turned from thinking about art to thinking about ema. At the time, Ishiko’s insights, which had the appearance of an all too sudden “change of course (betrayal?),” led him to detect as an extension of his “art criticism” of manga, a consumer item, an “appearance and disappearance” peculiar to ema as a folkloric custom. (Considering the close relationship between Ishiko and Lee Ufan that existed at the time, one cannot exclude the possibility that this is potentially connected to the non-substantial “encounter” that was characteristic of the later “Mono-ha” art movement). Clearly, Ishiko saw in the manner in which pictures painted while standing under waterfalls gradually disappeared the essential form of ema. Related to this is that fact that in the period leading up to his death, Ishiko was drawn to the unnamed, uncelebrated maruishi-gami (spherical stones worshipped as gods) scattered across Yamanashi Prefecture. To put it the other way round, like the action of a swordsman reversing the direction of his stroke to stab a second adversary, Ishiko saw in such a propensity for always disappearing at some point while existing naturally “modern spells” (Ishiko) haunting Japanese cultural properties and putting a priority on the exact opposite of this in the form of artificial and permanent conservation. And he continued to contemplate what kind of meaning these had with respect to his own art (or in my manner of speaking, to the art of the Japanese archipelago). Of course, there is a connection over time between these and Mise’s “mountain-like” inquiry through this exhibit (in a corridor-shaped ie, circular fashion) concerning the question, “Is restoration possible?” (To be continued)

1. Suginoshita Design Room + Aya Nakajima, 100 Stories Like a Mountain guidebook, 2018. The guidebook itself is counted as the first of the “100 stories.”

Yamagata Biennale 2018 was held from September 1 to 24, at the Yamagata Prefectural Local Museum “Bunshokan” and Tohoku University of Art and Design, among other venues.