III. Difference is Difference

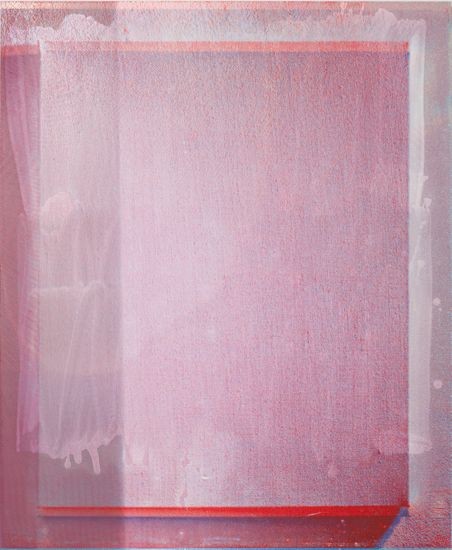

Untitled (2010), acrylic, silkscreen on aluminium, 86.3 x 58.4 cm. Photo Kei Okano, courtesy

Untitled (2010), acrylic, silkscreen on aluminium, 86.3 x 58.4 cm. Photo Kei Okano, courtesy Nathan Hylden and Misako & Rosen.

ART iT: Are there any artists today who really interest you?

NH: There’s several but if I had to pick some favorites I will say that right now I think On Kawara is really amazing. There’s an essential analysis of the practice of painting in his work, that’s something I hope to find in my own, the simplicity of his work makes it exceedingly complex to me. An essential aspect of painting is that it does exist in time, so there’s something significant about the act of doing it in that moment, and Kawara’s paintings are a very specific record of that.

Tony Conrad’s “Yellow Movie” (1973) paintings are also important for me lately, with the white paint that is gradually turning yellow as it deteriorates over time.

I think it would be great to put those two artists together. They share the idea that the object is always situated in time. I always like the idea that painting is not simply there but rather has the effect of being always switched on, projecting its presence. Even with the patterns that I make, the optical vibration gives a sense that the painting is “on.” This is perhaps why we use the word “painting” – a present tense verb – to describe an object. I am most interested in painting that investigates this temporal dimension.

ART iT: Similar to Conrad’s “Yellow Movie” paintings, looking at your paintings with the metal panels you feel the idea of some kind of chemical reaction taking place, suggestive of photo processing. Was that something you were thinking about?

NH: Not really, but it’s an interesting association. I like the flatness and the rigidity of the metal surface, but also with its reflectivity I like leaving it raw as a base material. I buy the panels from an industrial place, and normally you can see all the scratches that come out of the factory, which I leave as they are. In terms of the sense of presence of the thing, there are basic elements to each material: the canvas is rough, and the metal is metal.

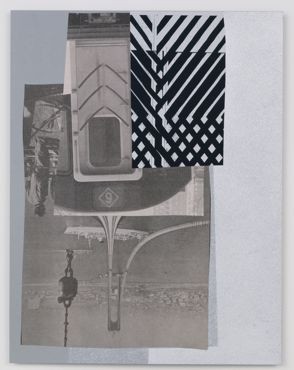

That’s why I use a lot of industrial materials. It allows a certain kind of surface to be made. In another sense it has a feeling to it. Maybe it even relates to the collages and the idea of construction and destruction happening at the same time.

Basically I found that in more and more of the canvasses, the use of color was about intensity, which in certain aspects made the surface difficult to look at or made it project its own kind of light. Then I started using specialized paints so that the colors shifted as you walked around the works but also created a strange displacement of the locality of the surface. In a similar but different way, the metal panels continue this interest in exploring the locality of where the surface lies. There’s always a play of where you would visually locate the surface of the painting, which is amplified by printing an image of a traditional support.

.

.

Top: Installation view of the exhibition “Still Now Again” at Johann König, Berlin, 2008. Courtesy Johann König, Berlin, and Misako & Rosen, Tokyo. Bottom: (Left) Installlation view of the exhibition “Starting to an End” at Misako & Rosen, Tokyo, 2007. Photo Kei Okano; (Right) November 8, 2007-2 (2007), collage and paint on paper, 27.9 x 21.6 cm; both images courtesy Misako & Rosen, Tokyo.

ART iT: Do you continue to use both canvas and metal panels?

NH: Something I’ve been doing lately is to have combinations of canvases and panels. The first time I presented the images on the metal panels I wanted them together with the canvases to illustrate the 1:1 aspect that the images printed there are printed to the exact size of the object that was first printed, because I like the idea that in reproducing the size, you’re making visible the 1:1 relationship with the referent.

ART iT: If all your works have an outside referent, does that make them narrative as well, or non-narrative?

NH: I try not to think of my work as narrative, because that to me would be about achieving a definite goal, whereas I am not really going anywhere specific. Another painter I really like is Robert Ryman, who would mount paintings with large bolts through the front because he didn’t want you to see them as pictures, but as definite objects. Working today, it’s both good and challenging at the same time is to consider the establishment of that fact and then complicate or contradict it. So there’s an inherent contradiction involved with using an image while also considering the idea of presence. For Ryman there was a definite narrative aspect from which you could view history and see a progression toward the physical fact that the painting is no longer a picture, but an object. However, to depictorialize painting is a contradiction in itself, because of painting’s inherent conventions. Now it’s more about utilizing that simultaneous occurrence of representation and objectivity, where you can have something physical and present but also pointing outside of itself. However, in the case of my work that pointing is circular as it leads back to the work or rather to another painting. In that way my work is non-narrative, in that circularity doesn’t lead in any direction.

ART iT: But couldn’t you say with your works that each piece narrates its own existence? To offer a parallel, in his Cosmicomics, Italo Calvino has a group of stories that take place before the existence of the world – for example, when the entirety of the universe was contained in a single point – and there was no space or time as such.

NH: The visible traces that remain from the making of the work do in some way narrate its existence. An argument I had with somebody in the past was about whether process could exist in the work or not. This was a painter who had a specific sense of the autonomy of the artwork, and his idea, which I find really difficult to accept, is that with the painting all you can have is what’s there in front of you. I like thinking that the visible traces of a process are a form of representation. So you can see marks and you don’t need to know exactly what they are, but they become a representation of the process of the production of the thing that you’re looking at. This is in line with the semiotic concept of the index as a form of sign. In that sense you can have a kind of localized narrative pertaining to each work.

I’m sure for a writer the idea of linear narrative would be an interesting thing to challenge, and thinking about different approaches as to what constitutes a narrative, and how to move outside the logic of progression. What I was thinking about as a bigger narrative for my own work is that it’s not necessarily about a development toward a definite goal, it’s just that difference is difference, from one to the next. It’s not that each one is somehow better than the one that came before; it’s just about difference.

Return to Top

Nathan Hylden: Process Present Tense