II. I believe in the skin

Monica Bonvicini discusses fetishism and the act of destroying her own works.

Hammering Out (an old argument) (1998), video color projection, sound, amplifier, two speakers, 18 min 45 sec. All images: Courtesy Monica Bonvicini and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin.

ART iT: You mentioned that in the 1990s you made works dealing with gender theory before starting to work with fetishes. What led to that transition? For example, was I Believe in the Skin of Things as in that of Women (1999) a transitional piece toward looking at fetishism?

MB: I would say that work was the close of a particular chapter. I had been reading all the books I could find about gender, and had to escape from all that theory for a while. I Believe in the Skin… was a way of coming to terms with that. I didn’t stop there, but for me gender theory was interesting because of its analysis of the construction of sexual identity, and the relation between that and architecture brings with itself a research into the realm of sex in general. Fetishism seemed to me to be a logical development to gender theory.

ART iT: But what happens when you put a love swing in the gallery space? Doesn’t that have a normalizing effect on something that is generally considered to be abnormal?

MB: I hope not. Love swings are nothing new. They were not new when I made The Fetishism of Commodity in 2002, and many more people know of them than would have you believe. I don’t think I took something that belongs to an alternative culture and exploited it for marketing purposes. My intent was to have people – and not in a relaxing way – think about space and art differently. In fact, I’ve never used regular love swings, which you could buy online or at any sex shop if you want. I made “double” love swings that I designed myself. I don’t like it when something that functions well in a specific community is made public for everybody – and I don’t think I did that.

The Fetishism of Commodity (2002), galvanized steel, chains, leather swing, Plexiglas, latex, 208 x 500 x 444 cm.

ART iT: Did you also have a formal attraction to S/M gear? Did you anticipate it having some kind of effect on viewers’ experiences of the space, or was it more about the connotation of the objects themselves?

MB: When I showed the first swings I also displayed drawings, which for me are, in a classical sense, a way of putting down thoughts and making plans for what could potentially be translated from the level of language into an object or sculpture. There was also a graffiti text based on a statement by Bernard Tschumi on how sensuality can overcome space, and I used cheap material that I felt could represent Mies van der Rohe’s idea of transparency in architecture. I made a fragmented cube-shaped partition using Plexiglas instead of glass, and partly oiled latex panels instead of marble. I wanted to express how as an architect Mies fetishized particular materials and visual effects, which I saw as being trapped into a personal taste that was independent of all the theorizing that has been written about him. To use a love swing was also perhaps a way of showing that.

Also, with a double love swing there is no determined passive or active way of behaving, whether you’re lying on it or sitting in it. In fact, once you’re physically in it, it requires some athletic effort to get out on your own. It was not a symbol, but of course physicality is part of the fundamentals of sculpture, in that sculpture always relates to a body or a space and is experienced through the body, and in this sense I think the love swings trigger different readings.

ART iT: Some friends recently took me to a legendary Berlin cruising bar. The moment we entered, everyone turned and stared at us intently. In such instances there is such a strong sensation of being looked at that it changes how you relate to your body. Do you think of the fetish object as also somehow reversing the gaze onto the viewer?

MB: I couldn’t say, but for me museums are incredibly sexy spaces because you are there to look, yet at the same time are looked at, whether by the guards or by other visitors. Think of the new MoMA in New York, with all these windows and glass partitions that allow you to see into other spaces. You might wonder why some guy is standing in front of a painting for so long, and decide that you have to go see it yourself. Even if you are completely alone, you still have all these people watching you from within the paintings.

I don’t believe there is any neutral space, and this applies equally to museums and galleries. This is what I love about Bruce Nauman, who almost forces you to go into the corridor to understand how his work functions [as in Performance Corridor (1969) or Live/Taped Video Corridor (1970)], or in the case of my work Plastered (1998), to walk on the plaster floor and break it, or to have the possibility to go on the love swings. These are all decisions everyone has to take on their own. It’s like being watched in some clubs. You look and act differently than if you’re buying vegetables at the corner store.

I must say that when I used to visit London or New York, my friends often took me to the kind of S/M and gay places that I would never have been allowed to enter in Berlin. I experienced these places as offering a freedom of sexual expression and desire that I didn’t know and still don’t know from heterosexual spaces. I never went to any swingers’ clubs, but I don’t believe that I would experience this total freedom of getting fucked, fucking, watching, dirty, not dirty, pain, whatever. I found it to be very liberating and positive, and on the other hand defining oneself as strictly heterosexual or gay to be very limiting.

Many people have written about me regarding gayness or pain and my use of chains. “Think about the slaves,” they say – it may be true somehow, but my experience of S/M practice, even if only as an observer, has been very liberating. I never associate it with something that is forbidden or dirty.

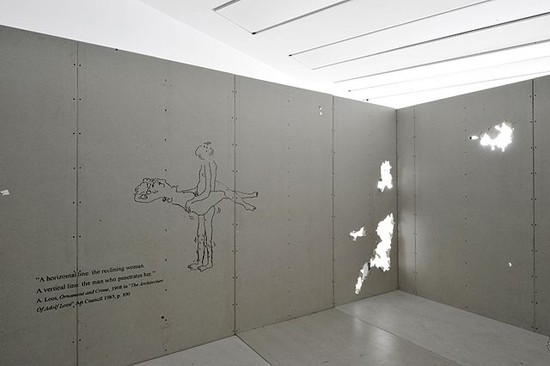

Both: I Believe in the Skin of Things as in that of Women (1999), drywall panels, aluminium studs, wood panels, graphite, 250 x 700 x 400 cm.

ART iT: In that sense is your work really about power dynamics, or is that more a projection made by people who are intimidated by your use of materials?

MB: Making work on power structures was really popular in the 1990s, and it meant something but it also didn’t mean a thing depending on what you were doing. There are power structures within the work or within the museum, or a personal experience, or what you encounter in your daily environment. In my case, it is the accumulation of all these experiences that forms the body of something to address. When you’re in the process, you can’t understand everything because there are too many people or things involved.

ART iT: Yet in works like I Believe in the Skin… or the video Hammering Out (an old argument) (1998), you literally attack physical structures.

MB: The first time I made I Believe in the Skin… was for a gallery exhibition in Vienna. I did the wall drawings and everything, and knew I was going to destroy it, but didn’t say anything to the dealers. I rarely do this, but I played the “sensitive artist” and said that I wanted to stay alone with my work the night before the opening. It took me hours before I could start breaking it because I was so afraid. I already had the finished work in front of me; it looked totally fine. But I built it to destroy it. The act required determination, mixed with anxiety. I went home very late. The next day when they entered the space and saw everything the dealers were completely shocked and upset.

I think there’s something beautiful in breaking your own work, because you’re not supposed to do it. Louise Bourgeois did that. And of course it’s a political act in a way, because somehow you’re devaluing your own work. It’s an extreme decision that you take; it’s your own work and you can do with it what you want. For me it’s about the physical act. I would never break the works in front of people: I don’t like to romanticize the idea of destruction. It’s part of the process and part of the result, but not something to display for everybody.

Return to top

Monica Bonvicini: Erect As Sin