NOT ONLY BLACK-AND-WHITE

By Andrew Maerkle

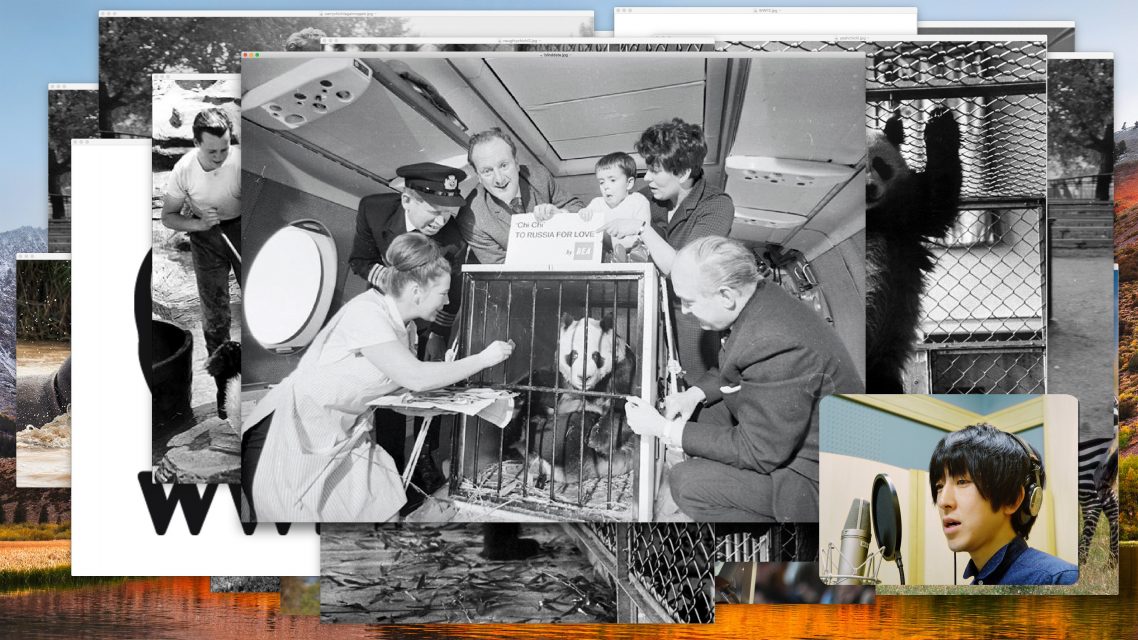

Black and White – Giant Panda (2018), single-channel video, 52 min 48 sec. All images: Unless otherwise noted, courtesy and © Hsu Chia-Wei.

One of the leading artists of his generation in Taiwan, Hsu Chia-Wei has embarked in recent years on an ambitious project to reconsider the history of Taiwan and its connections with other parts of Asia, from its complex relationship with mainland China to the legacy of its colonization by Japan and its unsettled position in contemporary geopolitics. Often taking the form of multichannel multimedia installations, his works often question the nature of mediated narrative itself. The sharp analytical wit and patient observational eye Hsu brings to his practice – as well as his timely exploration of nonhuman agencies, from gods to cancer cells to bats – have earned him widespread recognition, as his inclusion in biennale exhibitions in Bangkok, Busan, Gwangju, Shanghai and Sydney, all in 2018 alone, attests.

At the start of the year, Hsu was commissioned by the organization Arts Commons Tokyo to produce a lecture-performance, Black and White – Giant Panda, for Theater Commons Tokyo 2018, an event held at multiple venues across Tokyo. ART iT met with Hsu while he was in Tokyo preparing the production to discuss his practice in greater detail.

Black and White – Giant Panda was performed March 9 and 10, 2018, at the Taiwan Culture Center of the Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office. Hsu’s work is on view in MAM Screen 09: Hsu Chia-Wei at the Mori Art Museum through January 20, 2019, and in the 12th Shanghai Biennale, “Proregress,” through March 10, 2019.

I.

ART iT: In your work you have consistently dealt not just with Taiwan but also the region of Asia as a whole, as well as the historical connections linking different parts of Asia. What does the idea of “Asia” as a region mean to you?

HCW: My works are all primarily grounded in issues that relate to Taiwan, it’s just that those issues are not limited to Taiwan alone, but also relate to Asia as a whole. For example, the issues in Taiwan that relate to the colonial era, or the post–World War II era, or the Cold War era are all also regional issues. In particular, the experience of colonization is shared across much of Asia. The colonization of Southeast Asia by the British and French has parallels to Taiwan’s experience of colonization under Japan. In the process of colonization, the colonizers produced historical discourses of identification to make the colonial subjects identify with the metropole – for example, making the Taiwanese identify with Japan, or the Malaysians identify with Britain. This has led to many of the conflicts in the region. Although Malaysia and Indonesia are essentially neighbors, since one was colonized by the British and the other by the Dutch, the different colonial regimes ended up producing differences or even antagonisms between the two populations. Then following World War II, almost as soon as the former colonies gained independence and established themselves as nation-states, they were immediately caught up in the framework of the Cold War. For example, Vietnam was split into North and South, or Taiwan and China were set against each other.

So Asia has been affected by many different ideologies, but these ideologies are all political forms that were created by different governments or agendas. Sometimes they can feel very illusory. History itself is an illusion! The fact is there is no true history. History is always written from a specific position or perspective. This is one of the key issues I address in my works. My works question history and the way that these ideologies are constructed.

If my works only dealt with Taiwan and nothing else, they could easily end up supporting a certain ideology or view. Instead, my works often deal with the margins of Taiwanese society and locations such as Hoping Island or Matsu. Sometimes it’s enough to sketch the outline. If we always assert Taiwan is one way or another, then it can easily lead to the divisions in ideology I mentioned.

Above: Ruins of the Intelligence Bureau (2015), single-channel video, 13 min 30 sec. Below: Huai Mo Village (2012), single-channel video, 8 min 20 sec.

ART iT: Regarding imperialism in Asia, first there were the European Great Powers, then there was the Empire of Japan with its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, followed by the spread of the US military presence in the Cold War, and now mainland China is trying to establish political and economic hegemony in the region through policies like the One Belt One Road initiative. Asia has been treated as a territory for strategic domination throughout its recent history. Is this something you are conscious of in your work?

HCW: We tend to think of the Cold War as an event of the 1960s and ’70s, but in fact the influence of the Cold War can still be felt today. For example, although ASEAN has evolved into an economic entity, it was originally formed in the 1960s to counter communist activity in the region. And then even though the Cold War seems to be over, antagonisms between countries like the US and China continue to persist.

But whereas during the colonial period or the Cold War era many governments used propaganda to make the people identify with and support one ideology or the other, we no longer see this kind of top-down approach so much. We feel as though we have democratic societies, and now it is economics that drives everything – as is the case with China and the One Belt One Road initiative. Basically, what was once political conflict or propaganda war is now economic conflict.

It’s hard to say that my works directly address any single topic, but the works do achieve some kind of unity despite their complex backgrounds. Take Huai Mo Village (2012) and Ruins of the Intelligence Bureau (2015), for example, which both deal with the former Chinese nationalist soldiers who settled in the Golden Triangle region between Myanmar, Thailand and Laos. The soldiers ended up there because of the civil war between the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party, and then during the Cold War they got involved with the CIA, and now they are struggling to survive and create a livelihood there – which also ties back to China’s One Belt One Road initiative and current economic issues in the broader region.

ART iT: In Japan, publically funded cultural institutions seem to be motivated by the political agenda of cultural diplomacy whenever they work with Asian themes or collaborate with other Asian institutions. Are you trying to critically subvert or resist this kind of cultural diplomacy?

HCW: It’s not that I’m particularly trying to resist it, but when I go to different places and meet different people, and hear their stories, I see how everything we know is constructed. For example, Taiwan was colonized by Japan, so history books in Taiwan all write about the experience of Japanese colonization, but if you go to the Matsu Islands, which were never colonized by Japan, the history there is like a parallel reality. And then if you go to the Golden Triangle in Southeast Asia, the former KMT soldiers who live there will bring up yet another completely different history. We arrive at an official narrative through the influence of different politics and policies, but that official narrative is a fiction to begin with, because in fact everyone has their own history.

So I do not make works to prove that my interpretation is right, or that the official narrative is a fraud. Rather, my point is that there is no single objective viewpoint, only multiple subjective viewpoints, and the danger is when something that is clearly subjective gets presented as if it were objective.

Again, that’s why I always start my projects by meeting with people and visiting different places. When I ask someone about their past experiences, what they tell me becomes their personal history. So the works start from a very small point and then expand by weaving together different stories. They are not planned from the top-down like national policy.

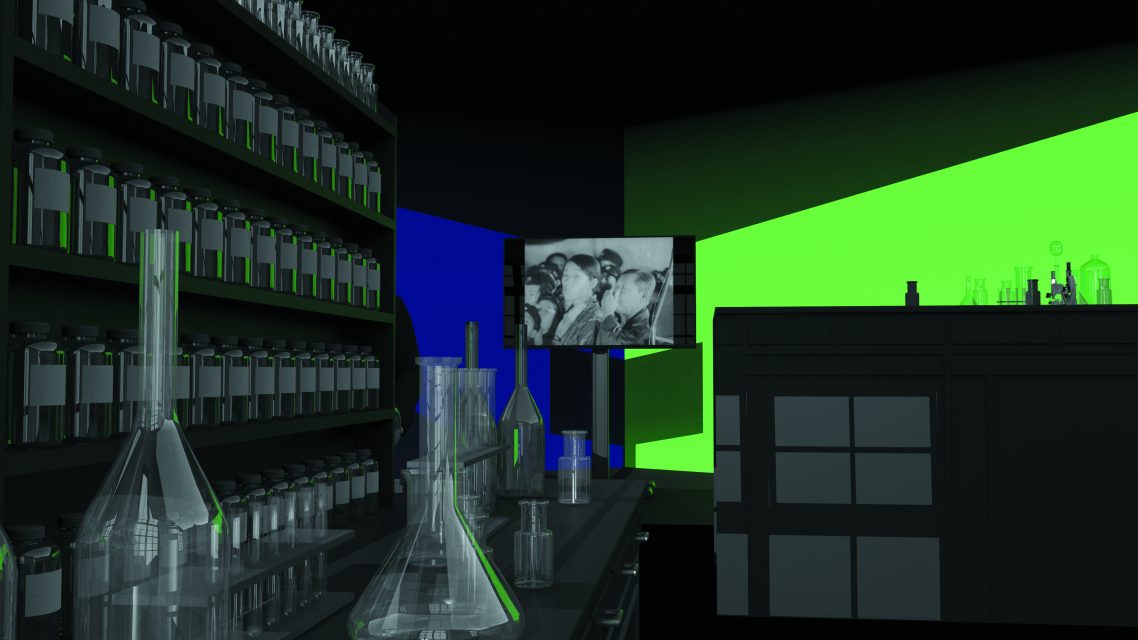

Above: Industrial Research Institute of Taiwan Governor-General’s Office (2017), single-channel video installation, 3 min. Below: Takasago (2017), single-channel video installation, 9 min 20 sec.

ART iT: The project you made in 2017, Industrial Research Institute of Taiwan Governor-General’s Office, deals with the Japanese colonial system in Taiwan, but it also touches upon the relationship between the state, technology and culture. How do you view that relationship in terms of your broader practice?

HCW: I’ll address this through my experience making Huai Mo Village, the work I shot in the Golden Triangle. The geographical term, Zomia refers roughly to the highland area between Thailand, Myanmar and the Yunnan-Guizhou plateau. According to anthropologists, this region was populated by people who settled there due to conflicts with neighboring states or who fled from their own states. Essentially, it was populated by wave after wave of refugees.

Now, the old method of anthropological research took the state or “civilization” as an analytical unit, so people would study the Indian civilization or the Chinese or Japanese or Thai civilizations. There is a lot to be said for that approach, but it doesn’t work in Zomia, because everyone came there from so many different places, and there are many things that are in-between and constantly shifting, things that are impossible to define as belonging to one country or another.

So maybe we need to change the perspective. Instead of using the nation as a unit, we could talk about how these people have come together to create a new way of life, a new culture. This culture is not some dead thing that has been fixed in place for hundreds and thousands of years. People are coming and going all the time, and the culture is constantly transforming and evolving. It’s the same with my work. There’s no way to frame it through a single country.

But Industrial Research Institute was a bit different from my previous projects, in that it led me to look at history from the viewpoint of science. Usually when we talk about the colonial history, we talk about it in terms of the pre- and postwar eras, but science offers a different scale for thinking about history that goes beyond historical periods like the Meiji era or what have you.

ART iT: In the Japanese imperial ideology, the emperor is not just a symbolic head of the nation; as the kokutai, he is the incarnation of the state. You made a work inspired by the Noh play Takasago, in which the connection between the pine-tree spirits of Sumiyoshi and Takasago is also a metaphor for the relationship between the emperor and his subjects. In your video Takasago (2017), which shows Noh actors giving a performance of Takasago in the middle of a modern perfume factory, are you trying to show how the power of the state or the colonial administration intervenes into even the most ordinary situations?

HCW: The perfume factory in Takasago is owned by the Takasago Corporation, which was founded in 1920 during the colonial era and sourced its materials from Taiwan. The main reason for the company name is that Taiwan was historically referred to as Takasago in Japanese. It might have had something to do with the Noh play Takasago as well. Someone might have thought that the two pine trees in the Noh play could also represent the relationship between Japan and Taiwan, and the Japanese would certainly have wanted to inculcate a sense of familial belonging in their Taiwanese subjects. We don’t know for sure where the factory’s name comes from, but the thing is that during the colonial era, they probably weren’t even conscious of a specific meaning to the name. There may have been some government policy or something that subliminally influenced them.

When I made the work, it was similar to my usual process. For example, if the story focused solely on the Takasago factory in Taipei during World War II, it would get stuck in a narrow frame. But by filming in Japan at the current, modern factory and having the actors give a performance of a Noh play that dates back to before the 14th century, it pulls what was originally the space-time of World War II back several centuries, while also stretching it forward by close to a century. So my approach is always to take something from a narrow frame and stretch its space-time to look at it from a broader angle.

Drones, Frosted Bats and the Testimony of the Deceased (2017), detail from four-channel video installation, each video of different run times.

ART iT: What is the significance to you of researching the colonial history and narrating it in the current moment – even if it’s done in an abstract way?

HCW: It has several aspects for me. First is that it allows me to investigate the historical process by which the current situation came about. There is a reason why things turn out the way they do. If you go to Cambodia, you will find that the Cambodians really hate the Vietnamese, and that the two people are hostile toward each other. But if we don’t try to understand the history behind that situation, and the past conflicts of the colonial and Cold War eras, then we would have no way of understanding the present situation.

Second is that the colonial period is now remote history, and many of the people who lived through it are dead. Sometimes when we discuss an event that our parents lived through, it can be too close to us, and we can get caught up in our love-hate relationship with our parents. It’s like looking at the news every day. But when we have a little distance, and there’s no longer anyone who experienced it around, then it can give us more freedom to investigate the event, to imagine it and take what we need from it. We can actually get many things that are useful to us in that way.

Every era has its own way of thinking, and different tools for thinking about things. Using different tools and methods will always produce something new, even when we’re looking at the same thing. People used to think that the world was flat, and that was their basis for viewing things. But after they discovered that the world is round, and has gravity, they could consider the event of an apple falling from a tree from a new angle, and think about what it is that made the apple fall. And then again someone comes up with the idea of particle physics, we learn that everything is made of particles, and that gives us a completely new approach for thinking about the same thing.

It’s like how there were many unexpected coincidences when we worked on Drones, Frosted Bats and the Testimony of the Deceased (2017), which was filmed at the remains of the Hsinchu branch of the Sixth Japanese Naval Fuel Plant in northern Taiwan. It turns out the bats we found in the plant are a very rare species that migrated there from Japan. And Takasago connects to the pine tree spirits, but it also has a connection to zircon ore, which was the subject of another work that relates to Japanese industrial projects during the colonial period, Nuclear Decay Timer (2017). And none of these things are human. In fact, I believe it really is possible to look at events from a nonhuman perspective. We think about World War II as a human issue, but if we were to look at it from the viewpoint of rocks or animals or trees, we might get some new ideas about it. We could write a history of World War II that would be completely different from what is told from the human perspective.

I | II

Hsu Chia-Wei: Not Only Black-and-White