Defining a Proposal Through Questions:

Jun Yang on the Taipei Contemporary Art Center

ON RECORD is a series of dialogues with contemporary artists about the ideas and influences that inspire their works. ON RECORD #2 was conducted in Tokyo and edited by ART iT in collaboration with Jun Yang.

From A Contemporary Art Centre, Taipei (A Proposal) at the 6th Taipei Biennial, 2008.

1. What are the origins of Taipei Contemporary Art Center?

5. What has the art center been doing since opening in February?

6. How do you envision TCAC if it’s still open after two years?

8. Who decides the programming?

1. What are the origins of Taipei Contemporary Art Center?

A group of 40-to-50 people including artists, scholars and curators in Taiwan have initiated a new space called TCAC (Taipei Contemporary Art Center) in two neighboring buildings – kind of classical narrow Taipei houses – located in the city center. TCAC opened in the last week of February and is now operating as a pilot project for the next two years.

The starting point of the whole project is that in 2008 I was invited to the Taipei Biennial, curated by Vasif Kortun and Manray Hsu. I had worked in Taipei before so I knew the context of what was going on there in terms of art spaces, and the situation of artists and curators. It was a very particular moment in Taipei, and at that time I myself was working on a long-term project about the conditions of exhibiting.

What is the space surrounding an artwork? Who controls the spaces, who finances them, for what purpose are these spaces built? How should a space for showing artwork look today? What are the local conditions, peculiarities and needs? As an artist I was interested to think about these conditions of exhibiting. Not necessarily in the context of an institutional critique or a social critique of the city or the site, but on a very basic level, researching fundamental questions related to the production of “artworks.”

When I was invited to the Taipei Biennial I thought it was a great chance to take this further. I could use the best-known exhibition in Taiwan as a research project to ask these questions across several layers. Even though the curators were considering showing one of my films or something similar I proposed a research project with the title A Contemporary Art Centre, Taipei (A Proposal). Within the question of the conditions of exhibiting I was “proposing an art center” without proposing a concrete image that might recall an existing art center; it was more about asking people to think of the possibilities for a space. What could such a space be? Would it even have to be physical? Who could, who would control such a space and with what intention? What are today’s art centers and spaces for exhibition?

For instance most spaces in China, or in fact almost all of them, are run as companies simply because there is no legislation for nonprofit organizations, nor is there government funding for such private initiatives. So where does the funding come from and how does it influence the structure and the space itself? These questions seemed particularly relevant in Asia.

I assembled a small team to look at existing models and past initiatives of art spaces in Taiwan. People who ran spaces in their apartments, artist-run spaces, smaller collective spaces, spaces that were funded by companies and so on. Looking at these examples, each of them expresses a certain condition, a socio-political situation and a necessity of being.

Recently I started teaching in art schools and universities in Austria and Taipei. It seemed that younger art students were concentrating on making their classical definition of an artwork. By this I’m not only referring to making “something to hang on a wall,” but also to the students’ realm of concentration – even within critical or performative or social interventions – the boundaries of their work definitions were still within a given frame. I don’t want to generalize, but there are still these tendencies: every gallery wants its artists to concentrate on producing their works.

So with the Taipei Biennial project one of my hopes was for younger students to reexamine this hierarchy of production where artists think, “I have to wait for a gallerist or a curator to knock on my door, or I have to apply for governmental funding and if I get it then I can do the work, and if I don’t get the funding then I can’t.” Even for artists who do not necessarily create visual objects, there is still the necessary moment of realizing an encounter between work and audience, whatever it may be. The same goes for curators as well.

More than their spatial characteristics or scale, their influence or their exhibitions, the essence of art centers has been that they bring together people who are interested in contemporary art. An art center is a platform for the exchange of ideas through the display of artwork, through provoking discussions and through creating opportunities for outreach. An art center is a reflection of the art community, ultimately becoming one of its voices and a visualization of contemporary art for the greater community.

If the goal of the Taipei Biennial project was to think about the conditions for exhibiting contemporary art, then building a physical art center was just one possible outcome of that project. But before that it was essential to think about the current circumstances facing contemporary art in Taiwan, taking a look at its financial, political and educational issues.

So what did we do during the Biennial? One, I occupied a pavilion in the park next to the museum. It was some kind of leftover building, a small glass pavilion that I turned into an office and research base. Because the sun heated up its interior so intensely, I created a wood façade in front of the pavilion and used it as a billboard, writing the title of the work, A Contemporary Art Centre, Taipei (A Proposal), on it in huge letters. I also placed a blue flag on top of the pavilion, with the idea of marking the site and giving the proposal a physical presence in town, like a pinpoint on a map. Even though we used the space as an office, most people who came were disappointed because they couldn’t see any “result.” On the second floor I had an installation of around 15 examples of existing and past exhibition spaces from the past 20 years in Taiwan.

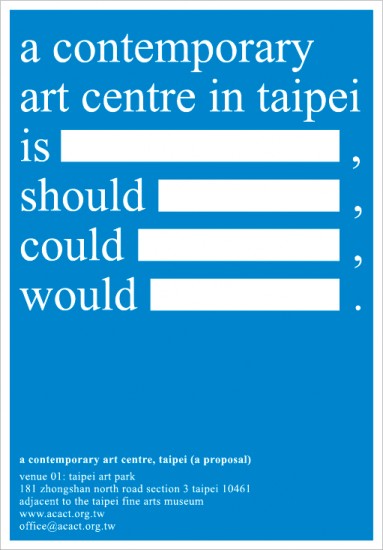

Additionally, I created a poster with the text “a contemporary art centre in Taipei is … (blank), should … (blank), could… (blank), would be… (blank).” People could write anything into the blanks – “Make my mom happy,” or whatever they liked. It wasn’t a survey, it was just a way to make the question more present. Then we organized gatherings of university art students, sort of like a series of parties outside, just to get them involved in the question.

One of the main ideas was to create a conference for 10 international art figures to discuss art spaces today. For instance, I wanted to invite someone who runs a gallery, like Hu Fang of Vitamin Creative Space, to reflect upon and discuss the idea of commercial galleries that overlap with the nonprofit platform of art centers. The goal would have been to discuss various models for creating spaces for exhibitions and visualization, as well as the considerations that go into that. But the more I thought about it and talked with people, I realized it wouldn’t have been very helpful or engaging for the local public. If I were truly interested in this question in the particular context of Taipei, I would have to think about how to generate a real discussion in town on existing models and future possibilities.

Like most museums in Taiwan, the museums are controlled by the city or the national government. Prior to starting the project with the Biennial I had worked with Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei, in 2006. It was then controlled by a hybrid private and city-run art foundation. In 2007 it was essentially reintegrated into the city’s art council, thus losing its independence, and has since been overseen by the city’s arts commissioner. The same department also oversees the Taipei Fine Arts Museum and organizations like Taipei Artist Center, which means that Taipei’s most prominent institutions are all in a very direct line of control with the city’s politicians. If the mayor changes, these institutions are directly affected, with the city appointing new directors for their programming.

Of course this situation occurs to some degree everywhere, but the question is, what is the distance between politics and professionalism, how many layers of independence and criticality can we create between these two poles? How do we define the “independence” of an independent art space?

In Taipei we had extensive discussions on this question of independence because some people define independence as refusing government funding. But coming from a European context I believe that it’s vital to take governmental support while challenging a city and a government to sponsor these spaces without controlling them, to actively protect and provide for freedom of expression.

If we look at many bigger state-run museums in countries around the world, they tend to function as extended political tools, which means that if there is the 20th anniversary of relations with Zimbabwe, they will do Zimbabwe exhibitions five times in a row and so on. This is not in itself a bad thing; every city should have such programming because it is important for other aspects of society. I think it’s very good in a way because it might create new opportunities for people to visit museums – why not? But I do think within the diversity of a city and especially within the possibility of a democratic government that a diversity of positions and viewpoints must be protected or upheld or nurtured in various ways. The problem arises when cities only support “Zimbabwe” exhibitions at the expense of other layers of production and communication, which characterizes the situations in both China and in Taiwan. This is the bigger challenge of the whole project, which leads to the question, what is the role of contemporary art in different societies? What is the necessity to sponsor these spaces and to support contemporary art, not just in regard to spaces themselves but also as in terms of artists and curators and their productions?

I have always insisted that even though at this moment TCAC is not receiving government funding, its long-term goal is to challenge the city and Taiwan to recognize that even if it’s something that cannot be controlled, it’s vital for a city and a democracy to support and create the possibility of these different opinions.

To return to the biennial project, instead of organizing an international conference, I started to think about how to host a local conference. The problem with local conferences is that many people simply might not attend or might not actually engage in a real dialogue because everybody is already familiar with everybody else’s opinions. So I decided to invite everybody to a weekend retreat in the north of Taiwan at a beach hotel. It had to take place away from Taipei since many people in the south criticized this project on the basis that Taipei, as the capital, is in itself a center and already home to a concentration of art and money. Since it was a retreat, all participants had to travel and nobody could just go home, since everybody stayed together at the hotel. I invited around 50 artists, curators and scholars. I purposely chose not to invite any officials, since it was more important to create a discussion rather then a face-off between government and artists, or a platform for officials to propagandize. I was interested in content. I felt that among 50 participants there would still be room for dialogue. And even though it was a relatively manageable number of participants, this retreat was the first time that so many people in the Taiwan art community had come together to listen to each other.

Nobody prepared anything in advance but we had three, primary discussion sessions, each having two moderators drawn from among the local art community.

The first session addressed the status quo of art in Taiwan. It was a chance to discuss where each participant thought the “problem zones” are. Why are all the art centers and museums under the control of the government? Why isn’t Taiwan producing more curators? Why are there so few exhibition spaces? What is the situation for independent curators and artists?

The second session went deeper into these problems and then in the third session we discussed possible initiatives that could change the status quo and produce a stronger voice for contemporary art in Taiwan. If we think with regard to Taiwan of the government’s stake in contemporary art on the one hand and then the commercial interest of corporations and galleries in contemporary art on the other, how far can contemporary art professionals go to produce a third voice that expresses an opinion on tendencies in cultural policy, or expresses its opinions on issues affecting society.

We had discussions about writing a petition, writing a statement, some people discussed the necessity of a new art association, others discussed the possibility of creating a new art space. We have a transcript of the whole thing, which is around 100,000 words in Chinese and is online for anybody to read.

We also had engagement in less formal settings like at coffee breaks, dinner and the bar, which we had booked out. In contemporary art, so many discussions take place in such informal situations, so I wanted to combine these informal moments of communication with formal discussions to create diverse scenarios for exchange. Participants included the curators Manray Hsu, Hongjohn Lin, Meiya Cheng, Amy Cheng and Wang Jun-Jieh, as well as artists like Chen Chieh-Jen, Chen Kai-Huang, Tsui Kuang-Yu and Yao Jui-Chung.

The third phase of this project was to “take over” a magazine. I convinced the popular Taiwanese art magazine ARTCO to let me guest edit an issue on the question of art spaces and my project (May 2009). I invited seven international contributors, each of whom are involved in an art space themselves, to introduce to readers four or five art spaces that they like, showing therefore the variety of today’s art spaces and expanding the definition of “art centers.” The final list included galleries, art museums, Internet platforms, alternative spaces and private foundations. In another section in the magazine I wrote three proposals for an art center in Taipei, as a way to sum up the research I had done to date. And then there was also a summary of the weekend retreat written by Meiya Cheng.

Even though the whole project was officially part of the Taipei Biennial, I worked almost completely independent of the Biennial framework, paying for almost 90 percent of the project by myself. And because of that, I did not need to ask for permission or go through bureaucratic processes for each step of the project. I asked the Biennial to provide me no more than the average – or even minimum – support for participating artists (eg, one flight ticket, five days in a hotel and minimum production fee). The rest of the costs I paid by myself or through my own sponsors. So I would rather say the project was produced in the context of the Biennial then to say it was a Taipei Biennial project.

Basically this was the conclusion of my Project. I had spent more then nine months working on it and felt quite relieved. It had created many discussions and also different possibilities for the future. Honestly speaking, as an artist these research projects can be extremely frustrating since I felt I was constantly talking to people and negotiating with them.

Then at one point the question of whether or not to “give it a try” cropped up. In discussions that followed the weekend retreat, participants already began to express their hopes and thoughts about experimenting with creating a new space in Taipei. Since everybody felt that such a space was missing, why not work towards initiating TCAC?

A core group met again in August 2009 to brainstorm about how to realize such a space, from issues like who would run the space to practical necessities and whether this new art center would actually need a physical space and if so, how big it would have to be. How could funding be created; what models could we apply for making decisions, how to include the community and so on.

From that moment on it became a collective project; it was no longer my concept, and my opinion became just one of several. A group of 30 people founded the art center – forming at the same time an association to ensure its future “independence” and to create an alternative to the classical power hierarchy. We did not want to create a museum with a director but instead think of an open structure where decisions would have to be made within a certain collective framework. Now the association has grown to around 70 members. It could easily have 200 members, but there is no point in having too many people since it would stall any serious decision-making. Also the TCAC does not only cater to its members, its goal is to stimulate and support the broader contemporary art field in Taiwan. Thus we include activities organized by non-members; basically there is hardly any difference between members and non-members at this moment.

The idea of membership is more related to legal considerations but also in anticipation of a possible future scenario in which TCAC actually does grow into an influential institution. What happens then? Instead of setting up a cabal of directors we felt that having an association could ensure the art center’s future balance through open board elections, such that the center has to constantly ask itself about its own necessity and direction over and over again.

This is something that would not necessarily be possible in a place like China, where it is illegal for citizens to form associations, because of the fear that such groups could evolve into political parties. Even if you were to form an association as a “company,” you would still be constrained in what you could do. And if you are running a space in Beijing it would be silly to challenge the cultural policy of China at this moment. It would be very silly to say, “I think the professional art people should organize themselves and be a counter pole to the existing governmental situation.” It would practically be suicidal. But on the other hand there are very critical projects taking place in China; the thing is how to find, within the system, possibilities for raising questions and discussing issues.

For instance, I work with Vitamin Creative Space in Guangzhou. At one point we had planned to show a video I produced for the Venice Biennale in 2005, but the work is actually quite controversial in China, so we had to ask ourselves, to what extent would it endanger the gallery and the people involved? In China you have to work with different strategies.

The same strategy we use in Taipei might not even make sense in Austria or Germany, because each locality has a very different cultural context for contemporary art.

In this sense TCAC is a very particular project that resulted in Taipei, and I think for every freedom we gain we ought to use this freedom as best as we can. This is also evident to an extent in Hong Kong, where the artists that I know there are also actively engaged in social and political issues.

So what happened since last August is that we started writing out the concept of TCAC, dealing with legal issues, possible future scenarios, practical necessities, how to fund the space, how to build its framework. We felt ultimately that it was important to have a building. Virtual things can be wonderful and enriching, but we felt it was important to give Taipei a real building – a new art center where you can go and do something there and it would be public.

We started negotiating with the city and several private companies, mostly real estate. The city was interested and has a lot of land, but it was important for the art center not to be hidden away on a mountain somewhere, it had to be easily accessible for young people. Art centers should not be tucked away in the suburbs; they should be in the city center next to the biggest cinema or whatever. But it was very difficult and time-consuming to negotiate with the bureaucracy, and we were more successful dealing with a real estate company. We finally came to an agreement with a company that frequently engages with contemporary art and design and architecture. This company buys up buildings one by one in different neighborhoods until they own enough land to create an apartment or office building. We were able to negotiate to have two buildings in one neighborhood in central Taipei. The relationship between TCAC and the company is that they provide the space, we do not owe them anything, do not have to do any exhibitions for them or seek approval for anything, nor do we pay rent. They have given us the space for two years; we did the renovation on our own budget.

There is something like a café or public space for small gatherings right at the entrance, and then we have the office also on the ground floor. The presentation, screening and discussion space is on the second floor, and exhibition space is on the third and fourth floors. The rooftop can be used for screenings and presentations as well. The office has a working station and an archive at the back, which is very important to the whole concept of the art center, while most of the events happen on the second floor.

Until now we’ve been primarily organizing screenings, sound events and discussions. We have only done a few exhibitions because they are the most expensive kind of event to produce: the production-, shipping- and display-related costs are expensive and for a small art center with no budget it is ultimately inefficient.

And also what the city was most lacking was a discursive space for initiating public issues or presenting various forms of contemporary art. For instance, if I have just finished a film, even if I take it to a museum, they cannot really fit it into their program because everything must be planned out far in advance. Nor would a gallery necessarily be open to doing an informal screening. So TCAC attempts to provide a more spontaneous element to local dialogue and exchange.

From A Contemporary Art Centre, Taipei (A Proposal), (2008).

Yes. Like I said, the project wouldn’t make as much sense as it does now if it were in Germany or Austria. The situation now – having a physical building for TCAC – resulted out of long discussions. Also the funding situation is very different to central European systems.

In the last few years, when you look at many countries in Europe, funding for contemporary art has been cut and you have private companies now sponsoring art centers, museums and so on. I am not using the phrase in a necessarily negative way, but this situation creates a conflict of interest – for example, when you have auction houses sponsoring exhibitions. It is a very complex issue.

It was interesting to look at this issue in Taipei because the structure itself is not that huge. The problems and the conflicts arose very quickly. Also within the broader background of the Chinese or Japanese context or other places in Asia, I thought it was very interesting to ask this question, since there is traditionally very little governmental funding for contemporary art, compared to the arts’ strong connection to the social state in European countries.

From A Contemporary Art Centre, Taipei (A Proposal), (2008).

As an artist you are always expected to deal with the local situation. As an artist you are invited to go some place and do a project there that has a certain sense of sustainability, but then how much can an artist create in a such a short situation, maybe going for only two visits in a year’s time? So I saw my project as a question for the biennial itself. I had been invited to several biennials prior to Taipei, and it’s pretty much the same expectations, no matter what the theme of the show actually is. It is in fact a strange situation for the artist; quite often the locals are not happy about “their” biennial. In many cases the local artists will feel left out and feel that these are prestige projects with very little impact on the local situation of contemporary art – a waste of money. The biennial flies in all these international people who then leave after a couple days of creating in many cases a so-called “site specific” work. So I felt that to develop a project with exactly these frictions of the biennial situation in mind would be a perfect frame.

From A Contemporary Art Centre, Taipei (A Proposal), (2008).

I’m not sure about the vision for the biennial, nor am I saying my contribution will resolve the problematics of biennials, but I think it’s an ongoing topic of debate. There are so many biennials coming up and Taipei is a very classic example where a very big amount of the city’s cultural funding goes into this show (although in fact it is relatively not that much) and once there’s such a flagship project the problem really is that it diverts money from other possible smaller-scale projects in town, and this is a real problem. Contemporary art is not a seasonal thing happening every second year.

For a city it’s certainly easier to market a biennial than a museum exhibition. But I do see many initiatives to question or to expand the possibility of these biennials. If biennials are a reality, and cities do think they are worthwhile marketing strategies, it’s not for us to say, “We refuse to work with them,” or “We must dismantle them,” but rather, we can view them as a tool that exists within our realm of possibilities, and then think about how to use them more critically, and how we can create something within that context that would lead to a stronger contemporary art environment, or more diversity, or how can we use them to implement certain discussions, critiques and so on. As long as we don’t just purely affirm the situation – and I think again this relates to the roles that we play, or our responsibilities as individuals – as long as we do not affirm these hierarchies and relationships but challenge them, then it can be constructive. I certainly don’t plan to recreate this project at every other biennial. I’m very happy that it’s done and can sit at home and work on the next film that I’m planning.

Exterior view of Taipei Contemporary Art Center, Taipei.

5. What has the art center been doing since opening in February?

When we started the whole project many artists stepped forward and offered to donate work. Around 40 artists donated artworks that we can sell to raise money – a small part of which goes to the artist as a production compensation and the rest going to TCAC. TCAC takes these works on commission for two years, during which we try to sell them. This is a one-time agreement; we won’t ask artists to donate every year; we are not trying to usurp the role of the galleries. We spent a lot of time talking to each gallery to say that it’s not a threat and that it’s vital to work together.

This was important because many people did feel threatened by the center, as it had accumulated all these supporters, a large space of 800-square-meters and created a substantial new entity within the city’s art scene. But the art center operates on a very tight budget, basically derived from the works we sell, but the bigger goal would be to push the government and private companies to contribute support to the project. At this moment we have to prove the necessity of the space first. We have had some success to this end because through our activities suddenly collectors have taken note and are interested in supporting us. And some galleries have realized that we are not a threat, and that their artists are involved in TCAC in any case, so why not support us. It sounds nice but I have to admit we have intense discussions, fights and talks behind every step of the way.

View of office facilities at Taipei Contemporary Art Center, Taipei.

6. How do you envision TCAC if it’s still open after two years?

We are already in the process of negotiating a long-term plan, looking for a building with a long-term lease, creating a starting budget and thinking about how to continue this project. But even if it stops, my personal opinion is that we have a minimum time limit to make the project a success. If contemporary art is always about renegotiating spaces and also the necessity of constructing spaces, then it is important within the next two years to experiment and try things out.

It’s the exact opposite of huge museums as enterprises such as the Mori Art Museum or Ullens Contemporary Art Center in Beijing where the institution has a big ambition to affect the art scene and it’s coming top-down but not necessarily responding to anything local, or perhaps not even able to provide a real space for professional discussions, since they are catering to the mass audience, which is not to say that they thus produce bad exhibitions.

Maybe Ullens had a genuine desire to create something of a discursive space for Beijing but I don’t think they were really on the ground thinking about how to do it. I think when Ullens had Fei Dawei as director along with an international group of curators, there was a real hope for creating discussions within the contemporary art community in Beijing, but I think this is now absolutely missing after changing both directors and curators and setting a new direction.

I think a discursive space or simply an exhibition space involves discussions and communication not only for critics and curators, they’re also vital for artists to reflect upon their works and to contemporary art production. And the vital thing is that these spaces need to be public. Of course there are many discussions in Beijing that take place in smaller groups, but these discussions should be accessible to younger artists and art students who are not invited to the in-group discussions and dinners. This is something that is in a way missing in Beijing. You will meet enough people in Taipei who say that as well of the art center. It’s very difficult. The art center tries to be very open; but then there are groups or people who I guess feel left out. The Friday Bar event is one of the tools we hope will be able to open the art center for the public as well as professionals from other fields of cultural production such as filmmakers and musicians.

When we started TCAC we discussed how this experiment could be different to an art center run by a small group. In a way, classically speaking, you would say that the small group itself has its own agenda and its actions reflect this agenda, thus making such an organization a kind of self-promotion and not necessarily about broader public issues affecting contemporary art. Also the group does not necessarily have to step into cultural policy or engage in discussions that are not really related to their agenda. What the art center attempts is to think about how to raise issues and support contemporary art with the broader picture in mind. For instance the archive in the office, which is publicly accessible, includes material from artists, scholars and projects associated with Taiwan that are not part of the association.

Installation view of the opening exhibition, “Donated Works Exhibition No. 1,” at Taipei Contemporary Art Center, Taipei, 2010.

I know Long March but I’d rather speak about a different but similar project since I have been working with them. Vitamin Creative Space in Guangzhou and Beijing started out as a nonprofit art space but given the necessities of funding the space and creating a stronger program, Vitamin now operates as a commercial entity as well. This is comparable to Skuc Gallery and Foksal Gallery in Europe, commercial galleries that started out as art centers or foundations.

I don’t really see a problem with that, because the gallery system itself grew out of a context at the end of the 19th century when commercial galleries first came into existence. So in this sense it’s a very old model that reflects a different necessity and social context from those that led to Vitamin or Foksal or Long March, which is very interesting to observe.

From A Contemporary Art Centre, Taipei (A Proposal), (2008).

8. Who decides the programming?

The association has elected a board that “controls” the art center and convenes every Tuesday at meetings that are open to all association members, although usually no more than 10 people actually show up. We’re trying to include more people but it’s an endless process. So at the moment we haven’t really found a smooth way of running it. When a lot of people come together we have to readapt our methods of communication and negotiation. But all the information is fully transparent and sent to every member for discussion.

In the beginning we didn’t have any intent to organize an exhibition because we didn’t have a budget, but because we received works donated from artists we decided to have a two-part donors’ exhibition. It’s interesting because the art center has a collection of 40 art pieces and in a way it’s a stronger collection than that of the city. We are now working on a bigger exhibition using even more spaces that will take place around the same time as this year’s Taipei Biennial, so that is our major project for this year.

We also have a series called Friday Bar, where every Friday one artist or curator or anyone else takes over the art center to host and create music events, lectures or discussions. Sometimes we even have several events on the same evening. These events are interesting because they open the art center as a platform for various people in the art field as well as various events and forms that are part of contemporary art. And then every month we do a Sunday art salon inviting younger artists to show and present their works outside of the regular university situation. So there are a lot of different activities.

Another thing is that all members of the association are invited to propose something. Again, practically speaking few people take advantage of this, and we are by no means overrun by proposals, but at least every week there are one or two events taking place at the center, constantly.

It does not mean all the events are extremely well attended but I feel the fact that there are people hosting events and people coming clearly shows the necessity for such a space in Taipei. It would be great if TCAC could work with other spaces in Asia as well, inviting them to do projects in Taipei or simply to exchange ideas on different strategies and possible approaches. This would depend mainly on budgets. In any case whenever international curators or artists visit town we ask them to do a presentation. The whole thing is just two months old and we are constructing the car as we are driving it – for example, we haven’t had time to finish the homepage yet.

All images courtesy the artist.