NEVER ENDING STORY

By Andrew Maerkle

Paradox of Praxis I (Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing) (1997), Mexico City, video documentation of an action, 5 min. Photo Enrique Huerta. All images: Unless otherwise noted, courtesy Francis Alÿs.

Born in Belgium and based in Mexico City, Francis Alÿs is currently the subject of a unique two-part survey exhibition organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo. Held from April 6 to June 9, “Part 1: Mexico Survey” brought together representative works from across Alÿs’s career. On view through September 8, “Part 2: Gibraltar Focus” introduces the large-scale project staged in the Strait of Gibraltar, Don’t Cross the Bridge Before You Get to the River (2008), as well as related works, notes and documentation.

ART iT met with Alÿs in Tokyo to discuss his practice in the context of his two-part exhibition at MOT.

Interview:

“Francis Alÿs: Mexico Survey,” installation view, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo. Photo Keizo Kioku.

ART iT: Spanning practices that include painting, drawing, sculpture, performance, video and installation, you produce a diverse body of material in preparing each of your projects, and even where many of the works are ultimately presented as videos, they each address a diverse range of themes and situations. What interests me is that on the one hand each work has a very protean identity, which can expand or contract depending on the situation, and yet each work can also be distilled into a specific document. How do you understand this dynamic in your practice?

FA: Well, thematically I’m probably more reduced than you imagine. I do indeed use a broad range of media, partly because, having studied architecture, I’m not trained in any particular media. So I collaborate with people who are proficient in a specific medium, while I’m often something like a producer, or an orchestrator, somebody who puts together a series of people to make something happen.

However, in terms of thematics, even though I wish I could be as broad as possible, when you look into it there are only a few ideas approached from many different angles. For a while people would talk in a broad sense of the tension between poetics and politics in my work, or how through a series of interventions the protagonist can be reduced to one individual, or a collective action, or an animal. But in the end it’s always the same few elements, which draw from ideas that I developed early on.

I think what’s interesting here in Tokyo with this two-part show at the Museum of Contemporary Art is that the first part was a survey – and it happened to be about the early works – while the second part is about a later work and more focused. My career is not that long, more or less 20 years. It started like an inverted pyramid, developing from one idea to another and continuing to expand outward, and then at a certain point – what is called mid-career – the pyramid reverted its orientation and things have started to narrow toward a single idea again. You limit yourself because you know you only have so much time and energy – conviction – left and you just try to cover the full extent of the original ideas you developed.

It’s a funny scheme, but the basic formula for my practice doesn’t vary that much. It’s always about trying to tell a story, and if possible a very short story that has some kind of grounded dimension, addressing a specific place at a specific time of its history, so that the work is very real but also leaves room for potential interpretations or even an allegorical dimension independent from its original context.

What matters is that the ideas have the potential for continued expansion. Three years ago I had my first real survey show, organized by Tate Modern, Wiels and MoMA – they called it a retrospective, which I think was a bit premature -. so I had to analyze what I had done, and I realized it’s most often the same idea bouncing back and forth and then eventually opening up to a new development that in turn leads to another development. There’s no master plan. It’s like a long narrative comprising a series of episodes, but in a non-chronological sequence: while you’re already at episode seven, you may find yourself starting to work on episode three, like Star Wars.

I think some artists can develop many different parallel investigations, but I find mine to be rather linear. I think in its expression it may appear very hybrid and dispersed, but thematically it’s more like a “route,” and I have to say I don’t know where it’s taking me.

ART iT: I feel your works operate on multiple registers. There may be one register that is consistent between each work, but there are also other registers going in different directions.

FA: Maybe it’s easier for you to see than it is for me. I’m good at sensing when I’m stepping out of my narrative, even though I can’t tell exactly what my narrative is. It’s a funny criteria. You’re invited someplace – say, Kabul – and because it’s such a fascinating and rich universe, even over the course of a one week visit you immediately come up with 10 options for response, but really there’s only one that fits the course of your narrative, and I know my work enough to realize which one I need to push.

It may not be the most sexy or heroic option, but if it fits the development of the longer story, it is the only one worth making, because once you commit, it’s a year-and-a-half of your life swallowed up in a 20-minute video or an afternoon event. It’s a good example of how you expand and expand, and then there’s a moment where you realize, this is more urgent than everything else, and then you kind of censor yourself. It can be frustrating, because sometimes it would be nice to start again fresh.

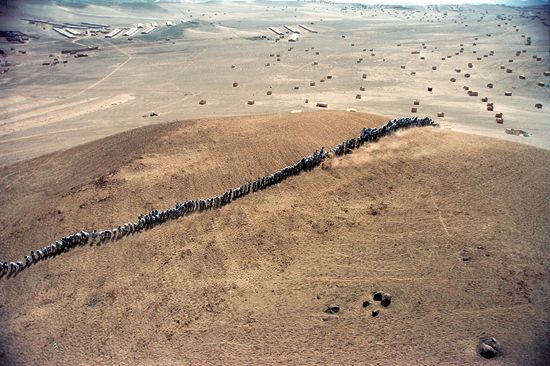

Top: When Faith Moves Mountains (2002), Lima, in collaboration with Rafael Ortega and Cuauhtémoc Medina, video documentation of an action. Photo Francis Alÿs. Bottom: Barrenderos (2004), Mexico City, in collaboration with Julien Devaux, video documentation of an action, 6 min 36 sec.

ART iT: So what are your core ideas? For example what connects a work like Barrenderos (2004), with the line of street sweepers pushing garbage through the streets of Mexico City, to your other projects?

FA: One could say that Barrenderos is an urban application of mechanics similar to When Faith Moves Mountains (2002), [for which volunteers used shovels to displace a sand dune outside of Lima, Peru], which itself was connected to my performance pushing an ice block through the streets of Mexico City in Paradox of Praxis I (1997), and so on. I can connect all the stories, but in a sense it’s superficial. If you understand too well what you’re doing, you stop doing it. If you suddenly see it from outside, then you lose contact with the boiling magma of ideas.

That’s why for a long time I was resistant to doing shows asking me to look backward. It’s a fragile moment. You realize, this is the extent of what I’ve been able to say, over several decades. Maybe I shut myself off a bit from trying to understand too well my production. I read little about what people say about it. It can influence your practice, and not necessarily in an appropriate direction.

Yesterday I was giving a talk at Tokyo University of the Arts and Yuko Hasegawa asked me about one of my earlier works, I think it was The Collector (1990-92). And as I was answering her, I realized that what I was saying was not what I was thinking at all at the time; I was just repeating what people had written about the work. I thought, This is bullshit! It’s terrible, but you can’t avoid it. That’s the contract. If you’re an artist and enjoy the vanity of showing your work to an audience, then people take it and make it their own, and eventually their reading becomes yours.

I was, say, 34 at the time, my life was totally different – everything was different – and I honestly don’t remember what made me do it. It just seemed like the most urgent thing to do then. Of course if I looked at my notebooks I could reconstruct somewhat the state of mind I was in at the time, but it’s certainly not what I said yesterday. So this self-analyzing – especially through others’ readings – can be very slippery.

ART iT: Yet you also have a practice of archiving, like the photos of the street vendors, Ambulantes, as well as the Sleepers and the Beggars.

FA: I started doing documentary or archive series when I realized that, like many other places, Mexico is a fast-changing city, and if you don’t document certain of its socio-cultural habits, they may disappear. For example, in 1999 when I visited Lima, the city had a huge community of street sellers, but when I went back in 2000, they were all gone. It’s possible to do that in a dictatorship. You declare that they’re outlaws, send in the army, and over a weekend, a whole tradition dating back to pre-Columbian days gets wiped out. Since then I started to more systematically document such “endangered practices.” It probably also has to do with my academic background in urbanism and architecture. More than architecture I was interested in urbanism and the history of the city and the passage from the medieval model to the Renaissance and modern city concept.

ART iT: Perhaps this model of the city as a fixed point that is also constantly in flux informs your interest in people who are moving, and your own movement through the city as well?

FA: Definitely. I’m not sure where Mexico City is heading at the moment. The way the global economy is standardizing everything, in particular the way in which cheap Asian goods circulate nowadays, has changed Mexico’s production tremendously. The opening of a bridge between Asia and Latin America, which on the one hand is fantastic and could never have been imagined 25 years ago, is rapidly affecting the whole social model and the local crafts, and it’s very unclear where it’s leading.

Top: A Story of Deception (2003-06), Patagonia, in collaboration with Olivier Debroise and Rafael Ortega, 16mm film, 4 min 20 sec loop, with cut painting. Bottom: Politics of Rehearsal (2005), New York, in collaboration with Performa, Rafael Ortega and Cuauhtémoc Medina, video, 30 min.

ART iT: You actually have a series of works – in which I would also include When Faith Moves Mountains and A Story of Deception (2003-06) – connecting the idea of rehearsal to deferred modernity in Latin America. I wonder if the reading of this whole body of work is changing with all these other developments?

FA: It’s changing. Modernity never happened in Latin America and it’s already been overtaken by globalization, which will probably also soon be surpassed by yet another kind of economy. So the “Rehearsal” pieces are pertinent to a very specific moment of Latin American history. I think the idea they were trying to express is still true at the level of society itself, but from a geopolitical point of view, things have probably already moved on to a different stage.

I would have to revisit more in depth what I was trying to say in the “Rehearsal” project beyond the Sisyphus aspect of progressing toward a forever deferred conclusion, but the mechanics of rehearsal themselves were a very effective working method that absorbed me for a good three years. I pushed it to its limits, applying its principle to animation, improvisation, videos, sound pieces, even theater. The striptease performance, Politics of Rehearsal (2005), produced for the Performa biennial in New York, is probably my only attempt at doing a more theatrical presentation. It was an excruciating experience. Both when you intervene on the street and when you perform in the theater, it’s a spectacle – there’s a public – but in terms of timing they are completely different spheres.

The video version of Politics of Rehearsal shows the one and only rehearsal of the rehearsal event that we produced the same night as a public spectacle. Between the private rehearsal and the later public performance, the content and even the development was not that different. The idea was that the slow progress of a soprano making her way through a lied by Malher, with her teacher accompanying her on a piano, would defer the end of a parallel striptease act. To do the rehearsal with the trio stripper/soprano/pianist was one thing, and because it was a true rehearsal it worked as a live event, but when it was staged as a theater performance it just died for me. The whole improvisation, the tension evaporated in the sudden self-consciousness of the actors.

ART iT: In the video there is a voiceover by the critic and curator Cuauhtémoc Medina discussing the relations between the striptease and the politics of underdevelopment and modernity in Latin America. Was this not part of the live performance?

FA: The voiceover came later, and it was probably the truest improvisation of all. I put the video on for Cuauhtémoc and asked him to just talk. He was watching the images and making comments and connections as the video unfolded. This is probably the final episode of that whole period, and what Cuauhtémoc said brought back together the essence of the project, and encapsulated many of our previous discussions, except in a way much better articulated than if I were to say it myself.

Top: Re-enactments (2000), Mexico City, in collaboration with Rafael Ortega, two-channel video documentation of an action, 5 min 20 sec. Bottom: Paradox of Praxis I (Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing) (1997).

ART iT: People often talk about the idea of poetics and politics in your work, but for me, in light of Cuauhtémoc’s discourse, the “Rehearsal” series also becomes polemical. Between the poetics and politics, there’s also polemics, where you’re making a specific critique about conditions in Latin America, and this is also reflected in the situations you created for the works and the way that you staged them.

FA: I was critical, because I was angry at what was going on. But I hope it’s not just that either. I think the word polemical applies when you bring it back to the occasion, which is very important. It’s a response to a specific situation. You try to respond to and address one aspect of what’s happening in a specific place at a particular moment, but you also try to create a story that doesn’t need all that referential information in order to exist. When you work locally and present it locally, it will be read one way, yet when it’s exported elsewhere, it falls under different parameters of reading, and the work still needs to have a life of its own; maybe that’s where the allegorical function enters.

I think there are several lives to a project. Some projects only manage to survive locally. Some projects when exported can lose their original meaning and evolve into something else, which can be a slippery process. Re-enactments (2000), [in which Alÿs carried a gun through the streets of Mexico City], is a good example. The work was about my own practice and doubts about my relation to video documentation. Mexico at the time did not have the association with violence it has sadly acquired nowadays; it was more like any other metropolis. But the vague connotation of violence that developed since then has introduced a different reading to the work that was far from my original intent. There’s nothing much I can do. I can tell the story, and I think more than anything it illustrates the independent life any project takes once you pass it on to the others. The viewer will see what he wants to see and will inevitably be influenced by the echo the place has at the moment he’s watching it, which could be 15 years later.

Getting back to the “Rehearsals,” they were probably one of the most time- and place-specific episodes on which I’ve worked, addressing a turning point in Latin America’s history. At the time Latin America was not a “fast growing economy.” We’re talking about the Salinas years in Mexico, which is the biggest fraud that ever happened in Mexican history in terms of making a whole population believe that Mexico was entering the so-called “First World.” NAFTA turned out to be nothing more than paper, and cost billions to Mexico for the vanity of belonging to the First-World club.

Yet the planet has changed an awful lot since. The whole balance and concept of progress has become quite different. Formally and allegorically, yes, something remains, and people now tend to read the “Rehearsals” more from a human perspective, as a kind of Sisyphus story, while the context and the occasion have been lost in the discourse, which could be a good thing. I haven’t talked about this work in a long time, and it’s interesting you bring it up. Again, I would have to reinsert myself into the moment when I felt the urge to make it, and then see how relevant it still is, or consider whether the situation has evolved in such a way that there is another story to be told.

From Tokyo, “Francis Alÿs” tours to the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, opening October 26 and continuing through January 26, 2014.

Francis Alÿs: Never Ending Story