Constant Traveler

By Frances Arikawa

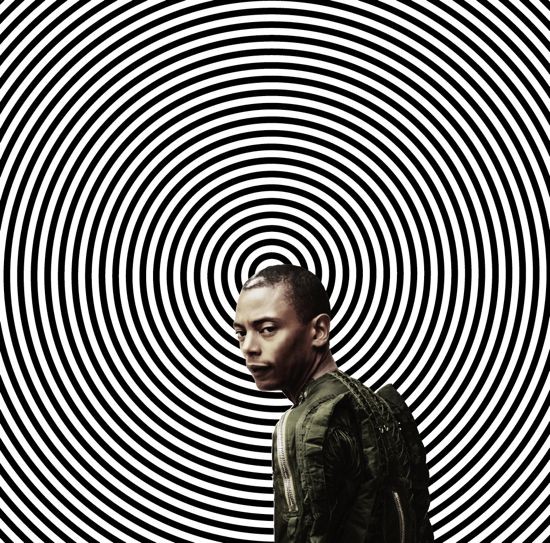

Cover art for Sleeper Wakes, released December 2009.

In an exclusive interview, ART iT talks with groundbreaking Techno producer and DJ Jeff Mills about his wide-ranging body of work. After rising to prominence in the 1980s as a radio DJ and member of the Detroit Techno collective Underground Resistance, in 1992 Mills founded his own label, Axis, in collaboration with producer and DJ Robert Hood. Since then he has continued to expand his projects to include rescoring films, with his version of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis premiering at France’s Centre Pompidou in 2000, and creating new media installations such as Mono, made for the 2001 Sonar festival in Barcelona. Among other honors, in 2007 he was named a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres by the Ministry of Culture of France.

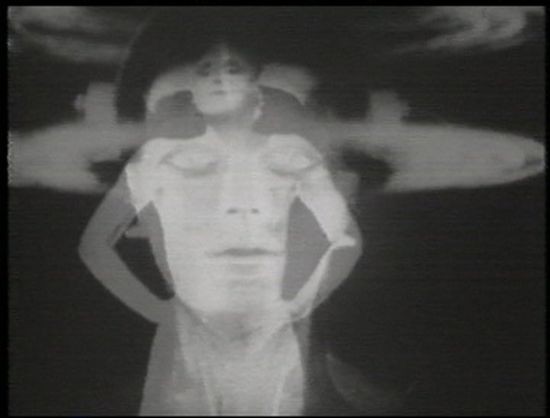

Still from the Jeff Mills rescoring of the film Metropolis (1927/2000).

ART iT: The rescoring of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis seems to be a turning point in your career toward projects spanning different media. What was your inspiration for the film project?

JM: Scoring a film had been an interest and desire of mine that started in the early- to mid-1990s. Many of us in Europe and the US had realized that the music had matured to the point where it should be applied to things other than just dance music. It had covered enough ground creatively to be able to move into cinema. Yet we had no examples of it and as far as we knew there had been very little action to try to integrate this music into cinema. So we sat around for years and years and discussed why that was the case, until the point that I decided something had to be done, that we needed to have a working example of how this music could further translate what people see on screen and in moving pictures. And so I came up with this idea to just pick a film, compose music to it and then play it to people and just see what happens. If anything, I felt that it could be used as an example in that way. I made a short list of movies and eventually settled on Metropolis, mainly because I found out that I knew someone who knew someone who knew someone that worked in the office that had the rights to the film in Munich.

ART iT: So was it ultimately a matter of simply having the right connections?

JM: It was more that we thought maybe I had a better chance of not getting sued if I just went to the video store, bought the movie, watched it, took notes, broke it into different parts and then composed music to it and pieced it back together, because that’s exactly what we did.

Following that I did some work with a film director in Paris, Claire Denis, who had seen the Metropolis piece and wanted to have some music in her own film. Then I did a project on Buster Keaton’s Three Ages with the film company MK2 in Paris. At the moment I’m working on rescores of Fantastic Voyage and the 1919 silent film Madame Du Barry for the Cinémathèque Française in Paris.

Above: Mono (2002), installation. Below: Critical Arrangements (2009), video installation for the exhibition “Le Futurisme à Paris” at Centre Pompidou, Paris.

ART iT: What about your installation Mono, was there anything you were trying to communicate through the work?

JM: Mono was my first installation, and was shown at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània in Barcelona (CCCB) as part of the annual Sonar festival. By that time the concept behind Sonar had become a bit formulaic and the organizers and I felt that perhaps it was necessary to inject more contemporary art into the program in order to have something that wasn’t completely dependent on electronic music, something that was more structural, something that was just art as is, not connected or plugged into anything else; something that could broaden the festival and maybe attract more art enthusiasts, not only music people. So I came up with the idea of creating a large, monolithic structure – in reference to the monolith in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey – that would be placed in a room with a large skylight where we could use the light to in some way measure people’s perceptions of the monolith as they encountered it. There was also a soundtrack that evolved and progressed throughout the time that people spent in this room, and then we filmed it and documented it as well.

ART iT: Do you think there will be more work like that for you in the future?

JM: Yes. I have more or less dedicated the latter part of this year to working on more art, more installations, more films and moving-image projects. In 2008 I also contributed an installation to an exhibition on the centenary of the publication of the Futurist Manifesto in Paris at the Centre Pompidou, “Le Futurisme à Paris,” and I came away from that with many new ideas to pursue.

ART iT: What about the concept behind your most recent albums, Sleeper Wakes (2009) and The Occurrence (2010)?

JM: Sleeper Wakes is a conceptual, time-based project for which I left Earth to travel the universe in search of new ideas and worlds, and then brought this information back to share it with rest of humanity in an event that took place on New Year’s Eve 2009/2010 at the club Womb here in Tokyo. Over the course of the four-year journey through space, of course I had to maintain certain tasks, such as spaceship repairs, and so The Occurrence revolves around a routine spacewalk during which I was caught in a radiation storm and unable to return to the spacecraft for protection. I didn’t detect it at first but from the radiation exposure I have developed a unique ability to control electricity and now those effects will be revealed in the music and concept of the next segment of the Sleeper Wakes project, The Power.

ART iT: Has technological advancement affected your work at all?

JM: Not as much as people might think. I’m not a technology addict. In fact, in many cases I actually don’t use technology at all. Maybe about a decade ago I realized that if I’m going to dedicate my life to music then the most valuable thing I should have is not necessarily my ability to use technology but actually my ideas about music and how it should be presented and perceived. Narrowing it all down beyond the software, beyond the computers and the mainframes, the original ideas have to be there, they have to be far-reaching. So I tend to pay more attention to the things that inspire me to come up with ideas like Sleeper Wakes, things like pulp fiction, science-fiction movies, NASA and spacewalking. I’m more interested in that than computer software per se, and so far it’s shown me that it’s more valuable to have expansive knowledge of man and space than it is to know how to sequence in 50 different ways.

ART iT: How much do those inspirations, like pulp fiction, take a part in your daily life?

JM: I spend many hours each night recording music, but use the daytime for researching and for looking at things, discovering things, collecting things. I have a collection of antique books from the UK and the US, and films.

These things are more valuable than actual keyboards and pieces of equipment because I can just as easily change the format for my ideas from, say, music to literature while keeping the same mindset, just using a different application. I find more and more reasons to collect these things and keep a library of all this stuff as close to me as possible. I think “geek” might be the official term to describe someone like me.

ART iT: In 2005 you collaborated with the Montpelier Philharmonic Orchestra for the one-day outdoor concert Blue Potential. What was it like having your music played by an orchestra?

JM: In the end it was great, but – and I know this from experience as well as from other people who have worked with orchestras – there is this compromise that automatically enters the equation because classical musicians think of electronic music as being a completely different animal to what they do. Electronic music fills the stereo field so that there really isn’t room for anything else. The delicacy of a violin or of a clarinet becomes lost next to the textures and the sounds of electronic music. And so there is this caution that is there from the very beginning.

If you can get beyond that, which we were actually able to do, if you can relay to the orchestra or to the conductor that the music is not so different, then everybody feels easier about performing it. I had to explain to them why things are minimal, that it’s not because you can’t change the structure of the song, it’s just that minimalism has a value in electronic music because you’re conditioning the people to listen to the same thing over and over again and it’s more about achieving a hypnotic effect where the people begin to relax the more they hear the same thing. I had to explain why things are that way and why they’re playing the same sequence over and over, the same scale over and over.

ART iT: Do you think you had any converts to electronic music because of that?

JM: I think so. Perhaps the biggest hurdle was showing that no matter what you call it, if the music has a message then it can be translated to different genres. If the initial idea has substance then it’s not a problem making it a country song or gospel song and so I think we succeeded in bringing more attention to electronic music, raising awareness that it’s not simply a genre full of amateurs or the result of a quick-and-easy do-it-yourself approach, that people put thought into the notes and chords they’re using, that it’s not just picking-and-choosing randomly or leaving everything to the computer.

ART iT: As an artist, how do you balance your conceptual projects and being an entertainer?

JM: One has to give to the other, that’s for sure. And it changes over time. From the late-1980s to the late-’90s I was mainly focused on the performance aspect of being a DJ and learning my craft, learning how to translate this music to people that don’t speak my language, finding the common threads for doing that. That led to minimal techno and minimal structures that stripped the music down so that you can speak to people more easily. After 2000 I turned towards production, pinpointing the things I thought had yet to be covered in electronic music and pinpointing the things that I found interesting for further exploration such as conceptual music. We had touched upon conceptual music in the early-’90s but then Rave came and blew all that away. I thought that was actually something that should be part of electronic music, and that’s how I got more into film and finding new ways to use electronic music.

ART iT: Do you find that your audience generally understands what you’re trying to do?

JM: I think that most people who follow the music understand overall what I’m trying to say, even though the intermediate parts are maybe hard to follow if you’re not already thinking about, for example, the planet Saturn and its rings. But I think that people generally understand that I’m making the music about these subjects because I think that they may be part of our lives later on. Understanding what the rings of Saturn are made of, or understanding how space travel works, and that you don’t just leave Earth and go straight to Mars, that you must spiral around the planets and slingshot to that planet and then slingshot back then connects to the idea of circular motion and the image of the spiral and things like that. I’m primarily making the music for the people who understand those concepts, and with them I can move as fast and far as I can, so it’s outside the structure of the music industry. I make as many albums as I can and hope these people can digest it as quickly as they can, and that’s the track I’m on at the moment.

With assistance from Combine Daikanyama.