WAYS OF SEEING

By Andrew Maerkle

Three Women (2010), installation view. All images: Courtesy Alfredo Jaar, New York.

Representing his native Chile in this year’s 55th Venice Biennale, New York-based mulimedia artist Alfredo Jaar recently visited Japan for the opening of the Mori Art Museum’s 10th anniversary exhibition, “All You Need is Love: From Chagall to Kusama and Hatsune Miku,” in which he is participating. ART iT met with Jaar to learn more about his work.

“All You Need is Love” continues at MAM through September 1. Additionally, a new work by Jaar will be unveiled in the Aichi Triennale 2013, opening to the public August 10 and continuing through October 27.

Interview:

Real Pictures (1995), installation view.

ART iT: You’re known for works that address contemporary social issues from a political perspective while critiquing the use of media in contemporary society, but I thought we could start by discussing an underlying theme in your practice, the idea of staging and theatricality. This is apparent, for example, in works ranging from Real Pictures (1995) to The Sound of Silence (2006), whereby the staging of the exhibition space is an integral part of the viewer’s experience. How do you approach this aspect in your work?

AJ: Well, I’m an architect and a filmmaker, and before becoming a filmmaker I worked in theatre. I wrote and directed plays, directed actors. I myself was an actor – the worst you’ve ever seen, but I was one for a short period of time – so I am interested in all those things. With my background in film and theatre and architecture, it is natural for me to create what Godard called the mise-en-scène, or the articulation of a scene. I incorporate these elements to facilitate the reading of the work. They are an integral part of the structure of the work, and they are there, designed by me as the architect, in order to transmit certain information about the issues we are dealing with, and also to force the audience to act within a space, within certain rules that have been set up for them. And, of course, all this is related to the work itself. It is not arbitrary. It is designed as part of the work.

ART iT: So you’re actively thinking about the viewer as a participant in the staging?

AJ: Absolutely. For me, art is communication, and I never forget that communication does not mean “to transmit a message.” That is not communication. In the technical definition of communication, it says clearly that you have to receive an answer. If there is no answer, there is no communication. Unfortunately, many artists forget about that, and this explains the huge gap between contemporary art and the general audience. The gap exists because most artists think that when they throw something out there they are communicating, but they’re not. In order to communicate you must receive an answer. Once you become aware of this, as I am, then you create a mise-en-scène that gives the tools to your audience to communicate with the work physically, intellectually and emotionally, and to respond to the issues we’re dealing with. That is the real objective of the mise-en-scène.

ART iT: How do you deal with the potential for didacticism in such an approach, which can be both positive and negative?

AJ: I am also very much aware of that. Because of my need for communication, I have a natural tendency to be didactic, so I am always controlling myself and trying to strike a balance between didacticism and ambiguity, or didacticism and poetry, or didacticism and information or content, and so on. You have to find the perfect balance between the two. The work has to transfer enough information to be didactic enough to communicate, but at the same time there must be some space left for poetry, and for mystery and suspense and the many other magical things that constitute art.

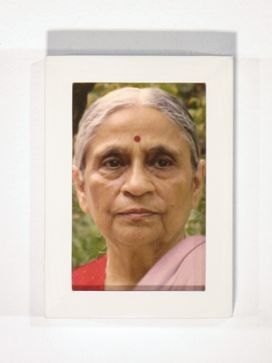

Both: Three Women (2010), detail.

ART iT: One of your recent works that interests me is the installation Three Women (2010), with stage lights shining harshly on the photographs of three important activist figures, Aung San Suu Kyi, Graça Machel and Ela Bhatt. I’m not sure where the images were sourced from, but you are literally shining a spotlight on the media to create a confrontation, not only with what these women do, not only with what they represent as figures who circulate in the media, but also of course with the way their images circulate.

AJ: You’re absolutely right. This work is part of a larger series that will be called One Hundred Women, so Three Women is just a prototype. I am testing it out, and if it works, I will continue. I have done the research and already have the list of 100 women; my studio has been working on this project for many years. I do not know yet what we will do with that list. Maybe it will become some kind of conceptual work, just using language, or maybe it will become One Hundred Women, exactly like these three. This work is first an acknowledgment that ours is still very much a macho world, and society still does not see women as equal to men. It is a response to that recognition, and it is also an homage to women in general, and a suggestion that if women were more in charge of the world, things would be very different from the way they are now.

So in this work, what I do physically is present three heroes of mine – women I deeply admire – and literally put the spotlight on them. Each one has six spotlights in different positions creating this aura of light around them. The punctum of the piece, however, where there is a dissonance or something that doesn’t quite fit, is that instead of having normal sized portraits of these women, there are tiny, three-inch portraits. So the audience is forced to get very close and discover who they are. It is my way to acknowledge their invisibility, and to suggest that these women deserve to be in the light, and I am asking the world, and the world of media, and us in general, to realize how important these women are. Each one is very important, and they are models of resistance in each of the areas where they work.

ART iT: In such projects, as well as those like the “Rwanda Project” (1994-2000), your works reveal how ideology affects what we see, and how we see, as well as what we do not see. But of course ideology itself is a very slippery thing to work with, because it is immaterial and always on the edge of consciousness. How do you deal with this immaterial aspect of your practice?

AJ: I’ve always believed that in order to act in the world I need to understand the world. Every work is based on understanding and knowledge. This means that every work is based on research. I am not a studio artist. I do not create works in my studio out of nothing or out of my imagination. All my work is based on reality, and reacts to a concrete, specific reality. My first objective is actually trying to understand reality. I spend an enormous amount of time doing research in situ. Once I accumulate a critical mass of information, I feel I have the right and the privilege and the opportunity to react and to start articulating ideas about the issue, but never until I have accumulated enough information.

I am aware that everything we do is essentially political, because I am releasing into the world an object that does not exist, and that object carries with it, whether we want it to or not, a conception of the world that I am sharing with an audience who might agree or disagree. Because of that, when I articulate my ideas in response to these specific issues, I try to make sure that I articulate that conception of the world with clarity.

This means it is not about making things, it is about thinking. For me, making art is 99 percent thinking and only one percent making. That is why, when you see my works, you realize that I am articulating ideas. It is not about materials, form, structure, texture, color, light. It is about ideas. You can see that, you can feel it, because the work is 99 percent idea. The remaining one percent is the last moment where I am trying to articulate an idea and present it to the audience.

Why does my work take so many different forms, from performance to film, video and installation, photography, object? Because I do not care about the medium. My work is not medium specific. It is about ideas, and then at the end of this long process, I use the material that I feel is best suited to articulate a specific idea. And I hope that when people are confronted with the work they would realize, this is not just a photograph, this is not just a video, this is not just an installation – this is really an idea, a conception of the world.

The Silence (2013), detail.

ART iT: You mentioned that it is essential for you to conduct research on site, but with both man-made and natural catastrophes like the genocide in Rwanda or the March 11 disasters here in Japan, there is an ambiguous ethical line defining the responsibilities of “witnessing.” What is your mindset when you enter such situations?

AJ: The mindset is very important. I control myself to go almost as a blank slate. I eliminate any preconceived notions that I may have had about the place or situation before I go there. It is an exercise I am used to doing, so now I can do it well. Before, it was more difficult and I would arrive some place and already have so many ideas and so many things in my head that I could not see clearly, because I was looking through the framework of my preconceptions.

But now, with experience, I am able to do that. I go there totally blank and let the reality sink in, let it teach me. That is why I insist on going to the site. I cannot do a work about a place without having been there, and been there many times. It is unthinkable. I am a frustrated journalist, obviously. I run into a lot of journalists in these places, and they do their job their way and I do my job my way. Again, we go back to this notion of understanding, and my visits to these places are about understanding them. I do everything I need to understand. I see, I witness, but I also ask questions; I talk, I find out. And again you have to be very responsible, and I start articulating ideas only after I think I have understood the specific reality. To do otherwise is irresponsible.

ART iT: How do you choose where to go? What is the criterion?

AJ: First, I am slow, so I do not do many projects at the same time, and then I am personally moved by the reality of certain places. I think I am a very well informed person. I am aware that at any given moment there are 37 conflicts around the world, and I am following them through different media. I start every day of my life spending two hours reading the news from both alternative and official press channels. I cannot start my day without that ritual.

I have mental folders – as well as physical folders on my desktop – where I keep things organized, and again it is about accumulating information. Most of the time, the information that I have gathered on a particular issue touches me to a point where I feel that I have to react, and then I go.

Of course, with time and experience and distance, I have become more and more resistant, because I cannot go to too many places at the same time, but there is always a precise event or moment or thought or gaze or something that triggers the moment when I decide to think seriously about a particular reality or situation.

ART iT: Taking up several years of your life and practice, the “Rwanda Project” is one of your defining works, and it also seems there was a clear impetus for you to act based on the disconnect between the actual situation, what the mainstream media was reporting and the response from the different governments and international agencies that could have intervened in the genocide. For other projects are you also looking for this kind of disconnect, a similar way to use media to draw attention to a vacuum of political action?

AJ: Each project is different. I do not have a standard set of issues that interest me. Anything can trigger a project, and everything is project specific. Sometimes the media might be an important issue within that situation, or it might not be. Sometimes there will be other considerations. I do not have any predetermined standards to measure a situation. I always start with a blank.

Top: Infinite Cell (2004), from the “Gramsci Trilogy,” installation view. Bottom: The Ashes of Pasolini (2009).

ART iT: For example, what triggered the Gramsci Trilogy (2004-05) in Italy?

AJ: It is very simple. By coincidence I had just started to travel frequently to Italy, and was being invited to do more and more exhibitions there, so I was understanding more and more about the Italian situation. This was when Berlusconi was in power, and of course I had to react to Berlusconi’s control of the media and so many other aspects of Italian society. Through his company Mediaset, Berlusconi controls 90 percent of the media in Italy. The average Italian is surrounded by a media landscape owned by Berlusconi whereby everything he knows about the world is coming from Berlusconi, and that explains why the Italian people voted four times for Berlusconi, and would probably vote for him again.

I thought to myself: I need help, so I will seek help from Antonio Gramsci, one of my intellectual heroes. Then when I finished re-reading Gramsci, I thought I have to bring back Pier Paolo Pasolini, who is another hero of mine. In the case of Pasolini, 40 years ago he was a fantastically critical voice, and if you listen to what he said at the time, it fits perfectly today, so in order to bring him into the present I made a film called The Ashes of Pasolini (2009).

I felt it was necessary to look for a Pasolini and a Gramsci in today’s Italy, in order to create a counter-balance to the hegemonic power of Berlusconi. And that is how the Gramsci Trilogy was born.

ART iT: If you look at the Japan of today, or even of the past several decades, you would be amazed to learn that there was a huge political movement that took place after World War II, starting in the 1950s and continuing into the mid-1970s, organized by citizens and by students, who marched in the streets and barricaded the parliament, attempted to storm the prime minister’s mansion, and fought with police – almost no physical traces of which remain in Tokyo now.

AJ: I totally agree with you. I’ve always been shocked at the lack of historical presence of those incredible moments. Another hero of mine is Shomei Tomatsu, who died recently. His “Tokyo Protest” (1969) is one of my favorite series of photographs. One of the best images from this series is that of a lonely man throwing something – you don’t see what he is throwing – while shrouded in a haze of chemical gas that had been fired by the police. I have accumulated many photobooks about that period of Japanese history, and also about the nuclear issue.

In 2008 I made a series of works in homage to the poet and activist Sadako Kurihara, who survived the bombing of Hiroshima, and died in 2005. Her book Black Eggs (1946/83) is deeply critical about Japan’s nuclear policies. She would have been shocked at what happened in Fukushima. She fought so much about this. The works I made about her were shown in Tokyo and Nagoya at Kenji Taki Gallery, but I felt they were quite ignored by most people, partly perhaps because I am a foreigner, and they might have thought, Who is this guy coming from New York? And she is a woman on top of that, so who cares? So nothing happened. But at least I did my homage to her and her work, and I have been thinking a lot about her as I prepare for the upcoming Aichi Triennale. The work I am developing for Aichi is also dedicated to her.

Both: I’ll always keep singing (For Sadako Kurihara) (2008), detail.

ART iT: Can you explain more about the Aichi project?

AJ: Sorry, but no. I never discuss a work in progress, because too many things can change. I only talk about my works once they are finished.

ART iT: Of course here in Japan following March 11 there has been a popular movement to reject the use of nuclear energy, but in last year’s general election the main party that supports nuclear energy, the LDP, was returned to power. This is another reminder of how the mass media – including new peer-to-peer platforms like Twitter and Facebook – is easily compromised by hegemonic power. In this context, what potential do you see for art’s political impact, or for revolutionizing the art experience?

AJ: I still believe in the capacity of art to effect change, because I think the world of art and culture is the last remaining space of freedom. We are still free to imagine and to speculate and create new models for thinking the world. I think culture still has a capacity to effect change. Nietzsche said that life without music would be a mistake. I think life without culture would be a mistake – would be unlivable. We have a role to play, because culture is important. It is up to the world of culture to decide what we will do with the privilege we have of speaking to a larger audience. Do we want to entertain, offer escapes, or do we want to encourage people to engage in a serious thinking process and try to create better worlds, and better ways to understand the world?

Alfredo Jaar: Ways of Seeing