PULLING STRINGS

By Andrew Maerkle

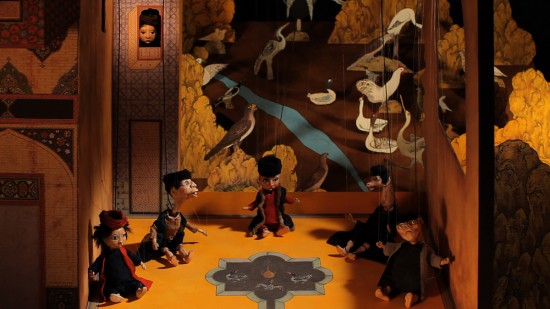

Installation view of “Wael Shawky: Cabaret Crusades” at MoMA PS1, 2015. Photo Pablo Enriquez, © Wael Shawky, courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Born in 1971 and currently based in Alexandria, Egypt, Wael Shawky works across diverse media, making everything from drawings, photographs and mixed-media installations to directing films and performances. He has risen to worldwide acclaim for his trilogy of films made with antique and newly commissioned marionettes, “Cabaret Crusades,” which retells the history of the Crusades (ca. 1095-1291) through Arabic eyes. Beginning with The Horror Show File (2010), which was produced during a residency at the Fondazione Pistoletto in Biella, Italy, the trilogy has been shown at institutions including the Serpentine Gallery in London, MoMA PS1 in New York, and Castello di Rivoli in Turin, in addition to being included in major international exhibitions such as the 12th Istanbul Biennial and Documenta 13. Interested in classical Arabic music and forms of storytelling, Shawky has also branched out into organizing live performances. For the Sharjah Biennial 11 in 2013, he staged a performance of a South Asian qawwali ballad – the lyrics of which were taken from fragments of curatorial texts translated into Urdu – in the streets of Sharjah, tying together issues of contemporary art and migrant labor. More recently, he produced the musical and theatrical installation Song of Roland: The Arabic Version (2017), for which the titular French verse epic is translated into classical Arabic and sung in the style of the 800-year-old fidjeri tradition of the pearl divers of the Persian Gulf. The work had its premiere in May at Theater der Welt 2017 in Hamburg, and is currently touring in Europe.

Shawky recently came to Japan for the opening of the Yokohama Triennale 2017, where part three of “Cabaret Crusades,” The Secrets of Karbala (2015), was on view in the Yokohama Museum of Art alongside a display of the glass marionettes that were used in the film. ART iT met with him at the opening to learn more about how the “Cabaret Crusades” trilogy was produced.

The Yokohama Triennale 2017: “Islands, Constellations & Galapagos” was on view at multiple venues in Yokohama from August 4 to November 5 of this year.

Interview:

Cabaret Crusades: The Horror Show File (2010), video (color, sound), 31 min 48 sec. All images: Unless otherwise noted, © Wael Shawky, courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery.

ART iT: The first thing that comes to mind in seeing this work, and also in thinking about the broader context of the “Cabaret Crusades” trilogy, is the question of what the marionette represents, and how the marionette functions as a medium. Why did you feel the marionette was the necessary form through which to approach this history?

WS: The idea of using marionettes came from reading about the speech Pope Urban II made when he launched the First Crusade in 1095 at the Council of Clermont in Southern France. This is perhaps the most important speech in the 200-year history of the Crusades, but it was not actually documented at the time. There is no original copy. Instead, there are four or so different versions of the speech, but they are all essentially reconstructions. This says a lot to me about the unstable point of view of history – even written history. As important as the speech was, it was basically invented by people after the fact. The wording is slightly different in each version, so we don’t know exactly what Urban said, but we do know the result of what he said, which was 200 years of war and occupation. This led me to think about authority and the relationship between the church or institution and the people, which absolutely has an aspect of manipulation or puppetry to it. In the first part of the trilogy I recreate Urban’s speech, and of course everyone is a marionette – including him, because maybe he, too, was being manipulated in a way.

ART iT: You made the first film, Cabaret Crusades: The Horror Show File (2010), using antique marionettes, which do not just have the function of representing the characters; as found objects, they also reflect something about the marionette itself and its cultural associations. But with each of the subsequent films, you changed the material of the puppets, first using ceramics and then glass in The Path to Cairo (2012) and The Secrets of Karbala (2015), respectively. Why is that?

WS: The first film was made with 110 antique marionettes from a collection in Turin. It was important to use European marionettes, and I looked through many different collections until I found the right one. I was lucky that the collection even agreed to lend the marionettes to us, as I did not expect it would be possible, but the Michelangelo Pistoletto Foundation played a big role in convincing them; one condition of the loan agreement was that we had to restore the marionettes, because some of them were in bad shape. On top of that, we had to change the marionettes’ costumes for the film, then replace the originals once we were done with them, so it was a big process of getting many people to work together to make it happen.

The first film was based on the Arabic point of view, so the main source was the book by Amin Maalouf, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes, but visually the film had more of a Renaissance look to it. There were two reasons for this. One is that we focused on the first four years of the Crusades, mainly centering on events in Europe, so it made sense to work with European marionettes. The other is that in European culture, marionettes were used not only for entertainment purposes but also for moral teaching, and so to tell the Crusades from the Arabic point of view using these marionettes was like a switching of the roles.

With the second film, the decision to make my own marionettes was related to the location. The film was produced in the city of Aubagne, which is more or less next to Clermont. This whole area, including Clermont, of course, is famous for making santons, the ceramic figurines that are used to tell the story of the nativity in the church. It’s a Christian tradition, it’s European, and it’s very connected in my view to the representation of the church. So I decided to try making marionettes using the techniques of this craft. It was a huge challenge, but it came out perfect. The second film deals with over 46 years of history. It spans from 1099, when the Crusaders had already arrived at Jerusalem and were settled there, to 1146, when the Muslim leader Imad ad-Din Zengi was assassinated. It follows all the internal conflicts among the Muslim leaders, who start to betray each other in order to protect themselves. So I wanted to connect the aesthetic to the Islamic miniature tradition, which is why the scenography has a more two-dimensional feel to it, but since clay is very connected to Islamic art, the ceramic figurines also evoke that tradition as well as the European Christian tradition.

For the last film, I was initially unsure about how to approach the marionettes. The film starts from 1146 with the killing of Imad ad-Din Zengi, and goes until the Fourth Crusade of 1204. I wanted something that could relate to that historical period, so I decided to make the Fourth Crusade the focal point of the whole production. Since I knew Venice was a key instigator of the Fourth Crusade, that led me to the idea of using Murano glass to make the marionettes. Each choice of material, from the antique wood marionettes to ceramic and glass, was connected to the story in some way.

Above: Cabaret Crusades: The Path to Cairo (2012), video (color, sound), 59 min 4 sec. Below: Cabaret Crusades: The Secrets of Karbala (2015), video (color, sound), 120 min.

ART iT: Why did you gradually change the form of the marionettes from having human features to having more animalistic or even monstrous features?

WS: There were a number of reasons. One is that I wanted to connect more to my drawing practice: I often draw hybrid figures blending human and animal features. It also connects to traditions of storytelling in Arabic literature – which are present in many other cultures as well – in which animals are the main characters or narrators.

For me, a big part of using marionettes is to escape from drama or acting. Because the marionette is an object, it does not require “acting” skills as such. There is only the character, because the expressions of the marionettes are essentially static. Viewers’ interpretations of whether the character is good or evil depend largely on how they project themselves onto the object. So the marionette is like a refusal of drama. And then giving the marionettes animal features makes it even more ambiguous. Sometimes I actually used the same marionette to portray both a Muslim leader and a Crusader, just by switching costumes. It complicates the moral aspects of the story. It’s not that one side is good and one side is bad. They are really all the same – driven by human desires, basically.

But the third film was more complex, because it had so many different layers. I wanted to give it a strong visual impact, so I decided first of all to make the scenography based on the paintings of Giotto and their use of color and decoration. But I was also thinking of the cosmologies of the time of the Crusades, which put the earth at the center of the universe and man at the center of the earth. That’s why many scenes in the movie show the characters interacting in this map-like space with the whole world revolving around them. And that also informed how I designed the marionettes.

ART iT: You say that using marionettes offered a way to escape acting or drama, but I imagine that manipulating the marionettes required great technical skill on the part of the puppeteers.

WS: It was a very difficult process. Especially in making a film with such large scenes, we had to adjust the set in relation to the scenography. Most of the time, the puppeteers had to be several meters off the ground to avoid getting in the shot. And since we were working with two or three cameras, it was even more complex, because we wanted to give the cameras the freedom to take in these large scenes. The ideal distance for the puppeteer to be in control of the marionette is around one meter. In our case, the puppeteers’ bridge was sometimes three or four meters high, and with such long strings, it was incredibly challenging to manipulate the marionettes. Moreover, the script was in classical Arabic, and I was the only one in the whole production – among some 80 people – who actually knew Arabic. The puppeteers had to approach it almost like music, so that they would know when to open the mouths and do the movements even without knowing the meaning of the words. It took a lot of effort.

ART iT: Did you produce all three films in Europe?

WS: Yes, one in Italy, one in France, and one in Germany. These are the regions that provided the main forces for the Crusades. Of course, Germany didn’t actually exist then, but many historical sources say that the first wave of Crusaders came from the Rhineland, or the area around present day Düsseldorf and Cologne. So it was amazing for me to make the third film at the K20 collection in Düsseldorf, after having made the second film near Clermont in France and the first one in Biella, Italy. If Clermont was where the Crusades were launched, Biella was like the engine for the Crusades, because the region kept sending soldiers throughout the entire 200 years.

Above: The Secrets of Karbala (2015). Below: The Secrets of Karbala, installation view in the Yokohama Triennale 2017, Yokohama Museum of Art, 2017. Photo Yuichiro Tanaka, courtesy Organizing Committee for Yokohama Triennale.

ART iT: Would you say the trilogy maps the origins of the Crusades in Europe?

WS: Yes, it was essential for the production to be in those places.

ART iT: So you start off with the idea of telling the Crusades from Arab eyes, but then produce the story in Europe with European resources, which undermines the expectation that we could ever arrive at a completely objective viewpoint.

WS: I think it’s really significant that the work was produced in Europe. Of course there was some money from the Arab world, but a lot of the support came from European sponsors – and even European governments. It’s so impressive to me that Europeans are fine with showing the worst parts of their history. All the crew on each film were locals. And with the last film, we were working inside K20. The curators gave me the biggest hall in the museum, which is almost a third of the total exhibition area, and let me use it for around five months to build the set and make the film. I decided to make the filming process open to viewers, so we built a big window at one end of the space from which people could watch us working. We couldn’t see them, but they could watch us throughout the day, and this went on for about three months or so. That added an element of live performance. But the whole crew were really engaged and supportive, even though they knew it did not present their heritage in the best light. It refutes everything that is happening today with people becoming increasingly nationalistic and close-minded.

Wael Shawky: Pulling Strings