III.

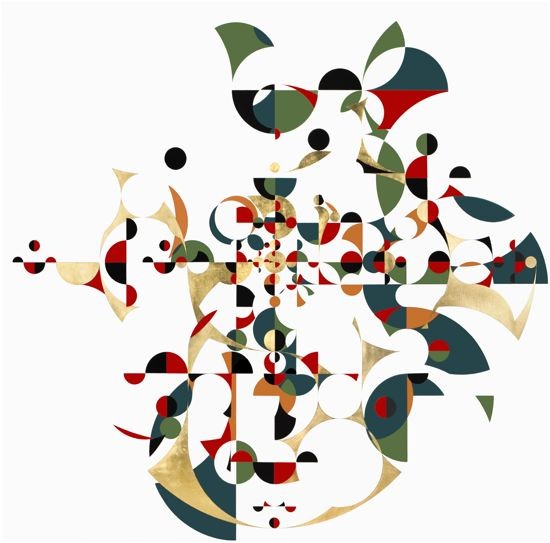

Boogie Frutti (2008), tempera and gold leaf on linen canvas, 200 x 200 cm.

ART iT: You mentioned how roundness is deeply connected to the physical world of perpetual motion, friction, collision and collapse. In that sense, could we say that although they have a geometric appearance, your paintings and drawings are also taking a step beyond the pure geometry of straight lines?

GO: But remember, I also use axles, so it’s not just the circle floating there. The axles indicate a possible direction. You have a point or a center, but through the axles it interconnects with different possibilities: either the same circle is moving to the north, east, west, south, down, up, or it’s connecting with another body coming from the north, east, west, south, down, up. They are bodies in constant connection or circulation. So although I don’t use squares or triangles, the moment you introduce the axles, they start to move and generate angles, or possible squares, but as trajectories.

It’s like the atoms in movement. When you generate the atom idea of the minimum unit, you also need to think about the voids between the minimum units and how they connect, and that’s why the axles became as important as the circles. The moment you generate axles, you generate a division in the internal circular form. That’s why I started using four colors, and then had them jump like the knight in chess, so that they behave three-dimensionally. The coloring of the paintings, as in the “Samurai Tree” paintings, is a three-dimensional proposition of displacement and movement.

ART iT: Were you already thinking about trajectory with the “Atomist” pieces, or were you following a simpler approach at that time?

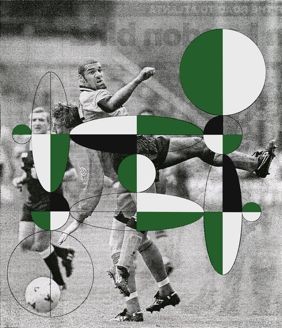

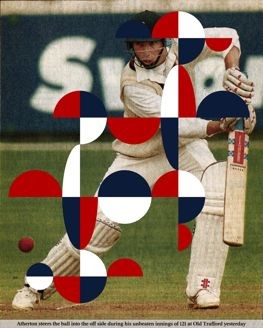

GO: The idea of trajectory is consistent. The colors are determined according to the same rules of advancing 1-by-2 or 2-by-1 for the knight in chess. They were taken from the dots of the photos themselves, and then blown up and superimposed upon the images in an arbitrary way. I wanted to see what would happen when you blow up the minimum unit of the photographic print and superimpose it on the medium, which is the representation of these bodies. How can you recycle the time of the photo, or the perception of movement in the sport image? So the axles were definitely important for that. Imagine the same work with just circles floating there, like gas or air – it would be very different. Here, you have a structure that connects the photograph with gravity, and the visual, rational distribution of perception – a possible grid – but also this structure means that the geometric shapes superimposed on the image function as a unity independent of the image. It’s not like I’m putting stickers onto a surface and suddenly two things are in contact. The shapes go beyond the surface to play with the different layers of the image, while at the same time remaining independent of the image. The idea was to find that balance.

Above: Untitled (2001), gouache on paper, 8 x 18.5 cm. Collection Fundación Jumex Arte Contemporáneo. Below: Horses Running Endlessly (1995), 8.6 x 87.6 x 87.6 cm. Courtesy Gabriel Orozco and Marian Goodman Gallery.

ART iT: What led you to remove the underlying photographs and develop this process into paintings with colors only?

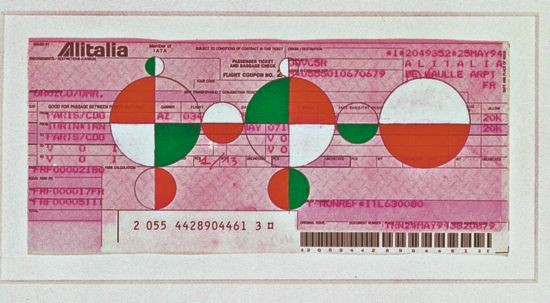

GO: I began with drawings in my notebooks, on blank paper, then I started to draw on pages with grids, like graph paper, and then on top of photographs in my notebook, and also airplane tickets and boarding passes, trying the process against a found piece of paper with readymade information. Then for the Gwangju Biennale in 1995 I did the lightbox pieces, “Light Signs,” which are very abstract, with no images, but are made with cheap industrial technology. It’s not a painting, it’s more like a logo in the street – a pharmacy logo or a traffic sign. And then I applied it to the sport images.

I think of this kind of personal, almost childish approach to playing with geometry as an instrument I can apply in many ways. It’s not about painting. It’s a way of thinking. So after trying out various applications, I next wanted to test it as a pure painting made with traditional techniques. I wanted to see if it would still hold as a geometrical system for building up meaning and an image that is interesting to see, but without any anecdotal aspect – without the photo, without the ticket – just as an act of painting. I was simply curious. That was in 2004, 10 years ago.

ART iT: Could the motif that is depicted in the frame of the painting theoretically continue indefinitely?

GO: It always concludes with the end of the frame. Obviously, it could go indefinitely, but the scale of the circles is relative to the size of the format, and the progression ends at the border. There are no truncated circles, although if you made a bigger field, they could of course keep going. So there is a sense of scale down to a millimeter-sized dot that grows into bigger bodies, but everything is flat, and the limits of the square are always there. Then you also have the deconstruction of the system through the introduction of overlapping circles, as in the big painting Boogie Frutti (2008), which explores the voids between the circles and different colors, and is all about being messy and playful and breaking my own rules a bit.

Left: Atomists: Jump Over (1996), computer-generated print, 210.8 x 179 cm. Right: Atomists: Offside, two-part computer-generated print, plastic coated, 196.9 x 156.8 cm. Below: Installation view of “Gabriel Orozco-Inner Cycles” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, 2015, with Ping-Pond Table (1998) in foreground and works from “The Atomists” in background. Photo ART iT.

ART iT: Is the body involved in the painting?

GO: I think it’s involved in the sense that the paintings pretend to have a connection with gravity, for example. They start form the center of the square, and then they have a direction that is vertical – a sense of verticality that has to do with gravity – as well as a horizon line. So you could say every painting has at its center a vanishing point or event horizon from which you start to bring the image out, and a gravity point in the axles. Even though the image is abstract, it’s trying to generate resonances and references across many layers in terms of diagram, landscape, body, planetarium, with the axles moving in a way that generates a connection with the symmetry of the body, as much as La DS (1993) is about the symmetrical coding of the body and the projection of a perspective or trajectory of the body in motion. Both approaches question why we have a symmetry that works for movement and displacement.

I also think of the mandala, and the way that the exercise of looking at a mandala or yantra relates to the body and concentration and breathing, the focusing of awareness so that you can empty yourself and look at something that is a kind of game in its own right. It’s like when you find people playing a game of chess or go in a park. As a spectator, you immediately forget about yourself and get absorbed in the game. It doesn’t matter what happened to that point. You concentrate on whatever is happening right then and there, in present time, and I think that also happens when an artwork is good or transmits something. But you need to know the game. Obviously if someone doesn’t know chess, they won’t care. Any game is an abstraction and you have to understand the logic behind it, but the moment you arrive to see it, you get engaged, your brain starts focusing and you spend a few minutes just watching other people play.

ART iT: The works in the “Corplegados” series are interesting to me in that sense, because with their eyeholes they are not just surfaces but also something you “look into.” Conversely, since they are displayed in hinged frames that allow them to be viewed from behind, they are also in a way something to “put onto” your body – a perception that is triggered when you gaze through the holes from “within” the work.

GO: “Corplegados” is a very strange work. It is among the most intimate and complex methods I have tried for incorporating my traveling, and the mapping of my traveling, into my work. Maybe it’s not as easy to relate to as the photos or the more basic and direct approaches. I understand that the paper I use, which is Japanese, is used to make patterns for clothing. You make the shapes and cut them out, and you can almost wear the paper before you proceed to making the actual clothes. It’s very resistant material. You can fold it and stretch it and it still holds. It’s light, but sturdy. That’s why I decided to cut it at a scale that is connected to the body. It’s paper that is made for the body, and then I divided and folded it as a map, which I carried in my luggage – but as a blank map that had to be completed. Then, as I traveled I would unfold the paper on the wall and make different actions on it with ink, writing and collage, so it became a kind of existential map, but very abstract and not anecdotal. At the end, the cutting of the eyes was a reference to the proportion of the paper in relation to the body, and that’s why when you open the work up you can see through it, because you can see the back of the paper. I like the “Corplegados,” but I have the feeling they are very exotic in relation to my other works. I consider them to be existential maps.

Installation view of works from “Corplegados” on display in “Gabriel Orozco-Inner Cycles” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, 2015. Photo Eiji Ina, courtesy the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo.

ART iT: But you deliberately offer the viewer the opportunity to see the opposite side of the map?

GO: Yes, exactly. Maybe that’s what we could call the “return of the repressed,” because you see all the patches and the work behind the scenes. Sometimes it’s boring. I’m not claiming that it’s nice to see. Some of them have a lot of information on the back and some of them not so much. C’est la vie.

Gabriel Orozco: Ineluctable Modality