IV. Wallfuckin’, Revisited

Monica Bonvicini on the necessity of taking risks.

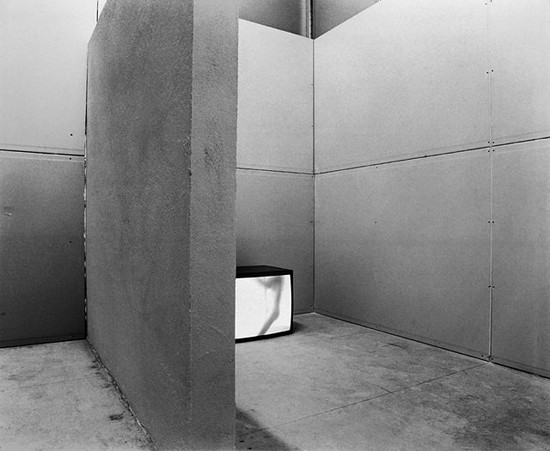

Wallfuckin’ (1995/96), b/w video on monitor, sound, amplifier, speakers, drywall panels, aluminum studs, bricks and mortar, white paint, door, 250 x 310 x 330 cm, duration 60 min. All images: Courtesy Monica Bonvicini and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin.

ART iT: You were just saying that you avoid mixing your personal life with your art. This seems particularly evident in the case of your sculptural works, which have this precise, almost calculated image. Is there a lyrical or emotional side to such works as well, or are they meant to be entirely calculated?

MB: Well, I think you have to be precise. Like I said earlier, if you’re mixing everything together in order to extract one essential element, then you don’t want it to be half-filled with your emotion, or it wouldn’t be necessary to do all that work. I may feel closer to some works, but once I exhibit them they are all open to the public and no longer belong to me. They are there for other readings.

ART iT: Then are your text drawings of words like “me” or “prozac” almost satirical in their use of language?

MB: That I cannot answer. Certainly drawings are different from sculptures. I’m constantly drawing. Sometimes I can’t believe what I’ve done because some are messy and others are detailed and perfect; sometimes I can concentrate and sometimes not. The drawings are indeed much closer to me.

Most of my sculptures I don’t build myself. I spend more time thinking about problems like what kind of screws and materials to use, and what is possible or not, so at a certain point I’m no longer there in a personal way, and thank god for that, because otherwise I wouldn’t be able to decide anything.

ART iT: As a way to tie up some of the themes we’ve been discussing related to politics, power and language, I’d like to ask about your commission for the 2012 London Olympics. As an artist, how do you deal with the visibility of events like the Olympics and their instrumentation in business and politics?

MB: This is a good example of what we were discussing about power structures and not knowing exactly why you’re doing things or what they’re all about. Officially the sculpture for the London Olympics has a budget of 2.1 million pounds, as I read in the newspapers. Yet I won a competition for a permanent light sculpture with a budget of only 1 million.

I didn’t apply for this competition because of the Olympics. I did it because it’s a permanent piece and the budget would allow for something interesting. Big projects like this or the one I did in Oslo, She Lies (2010), are so different from working on a show. I don’t like to do much public art; I don’t like public art in general and don’t want to become one of those artists who only does commissions, but occasionally it is interesting to do a big project because you have to think about gigantic spaces and sites that are not yet built, and the budgets are completely higher than what you normally have, so it requires a different approach. I also think as a female artist it’s important to do big things since high-profile commissions still tend to be awarded to male artists, because there’s still this idea that they can do better with money.

Top: Run (2010), permanent light sculpture for the London Olympic Park 2012, mirror-polished steel, glass, LED, three letters each approx 900 x 500 x 120 cm. Bottom: She Lies (2010), styrofoam, concrete pontoon, stainless steel, reflecting glass panels, glass splinters, anchoring system, size above sea level 1700 x 1600 x 1200 cm.

ART iT: Does the choice of the word “run” respond to the context of the Olympics?

MB: That’s a good question, because I too would make fun of a sculpture that says “run” for the Olympic Park. How much creativity or fantasy is there in that? But when I made the proposal I didn’t think about the Olympics. In 2000 I had a solo show called “RUN TAKE one SQUARE or two,” and for it I made an edition called “Run” with 15 pages of titles of songs from the 1970s with the word “run” in them: “Run, Run, Run”; “Running Dry”; “Run Angel Run”; and so on. In English I love the idiom, “take the money and run.” The word “run” means so much and is used in so many ways that do not happen in German or Italian. And London is such a vibrating, experimental city with a huge history of music, so I thought about that.

Also, there will be apartment buildings erected across from the site and the people living there will see the work every day. I grew up in a new village myself: you don’t have any place to meet because nothing is really completed; you don’t have any history, no place to go where everybody always meets because there was nobody before you. I thought it would be nice if people could plan to meet up at RUN or if RUN could become a place of identity for the residents there.

ART iT: Returning to the beginning, another reason I’m interested in the idea of political expression and art is that over the past decade there has been such a strong commercialization of contemporary art that I think we need to reevaluate the potential for political expression under such conditions. I am a bit cynical regarding the idea of how political expression now circulates through major institutions, but also must admit to romanticizing or even idealizing how it operated in the past. Having worked throughout this period, do you think there has been a normalization of political expression in contemporary art, or would you even call it as such?

MB: I wouldn’t. I don’t even like that term: it’s so sad. I always think there are so many more possibilities. I do see more students now who apply to the academy because they think it’s cool to be an artist. I thought sooner or later this would happen, but it’s especially apparent in the past two years – young people believing that it’s possible through art to make money and attain success and be invited to parties and so on.

I am also tired of seeing all these projects on Modernism, with the nice camera work for example, which are literally circling around something that is already there. I don’t get the critique because even if I go to a movie, which is only rarely, I have this idea that I should leave having learned something, and that’s my approach to art as well. This is not necessarily about seeking out didactics. Sending a camera around a Le Corbusier house is boringly didactic. I think, “Fuck, you’re young, you have a great camera!” Ten years ago it was impossible for a young artist to do that, and I don’t get what they want from this now.

But I also have students who are working politically, so I wouldn’t put everyone in the same pot. And it’s clear there are many young people who are into politics, perhaps more so than 10 years ago. Politics is still important for everybody.

ART iT: I agree that for young people politics is important, but is art necessarily the best vehicle for politics now? Maybe there are other ways to express such ideas?

MB: I have the impression there are young artists working again with gender issues, so there are cycles in how fashionable a theory is or not. Until five years ago, every time I even used the word gender, my students would immediately go on the defensive. Maybe we just need a little time until it’s back again. I hope the time will end soon when I see all these delicate sculptures pieced together from different materials, which I think are totally conservative, especially in times of economic crisis. You don’t hurt anybody. There is no risk.

I think art is beautiful because you can do everything, and to build up rules from the beginning so that you are safe is very sad. I also feel that, unfortunately, young artists who do something clearly political can often be boxed into a corner by critics and curators, irrespective of how their works look.

Plastered (1998), drywall panels, styrofoam, dimensions variable.

ART iT: Do you still have a sense of risk when making your own works?

MB: I’m very ambitious and controlling, but also get bored easily, so I try not to repeat my works. I want to be surprised by what I do. I remember when I made the video Wallfuckin’ (1995), many people asked me to do a variation of it, and I didn’t even know what that meant. I’m sure that if I had done it, I would have sold it and made some money, but everything I wanted to say about that idea was already in that one work, and I had no desire to repeat myself. This is an attitude I still maintain. I don’t know what you have to lose, actually.

Return to top

Monica Bonvicini: Erect As Sin