III. Frames of Action

Tomoko Yoneda discusses art in Japan after March 11.

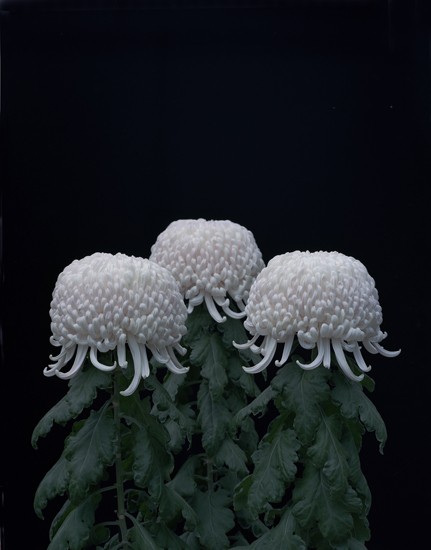

Chrysanthemum (2011). All images: © Tomoko Yoneda, courtesy ShugoArts, Tokyo.

ART iT: In your career to date you’ve shot at various locations and in different regions, and in the resulting works you present a more or less objective narrative that allows for the possibility of viewers to develop their own individual interpretations. On the other hand there are also aspects of your personal identity that you cannot escape. You started off working in Europe, and have gradually shifted to working in Asia. Does this affect how you respond to the themes you want to explore> Have you thought much about how to deal with such issues?

TY: I think that’s something I still have yet to overcome. It’s difficult, yet unavoidable, so it’s something that I’m always thinking about. I was talking with another artist recently about how visual artists, being neither professional sociologists nor politicians, must do whatever we can as artists. Being in the world, living wherever I live, no matter what I say or how I dress it up, it is impossible to escape society. So now, being in Japan, when I photograph here I must also account for the inescapable presence of Japan’s past and history, and how I process and express that is indeed my greatest challenge.

ART iT: This time, in the process of photographing in Japan have you felt any change in your mentality, whether from a purely physical stimulus or from a sense within yourself that now is the time to address Japan?

TY: I feel that perhaps now is the time for people in Japan to look critically at the situation around them. Before, everyone spoke of the complacency of peace, but that can no longer be the case after March 11. I have come to understand now that the stories that need to be told must be told, and formerly naïve artists must think carefully about their individual positions and what they want to say, taking responsibility for the works they make. I myself have always tried to be self-aware in my practice, but now I believe I must be even more rigorous in my approach. And even in terms of how my work is received, I feel that maybe there is more potential for people to appreciate what I am doing.

ART iT: In that sense when you’re dealing with Japan it’s easy to imagine you lose some of the objectivity that you apply to other locations. How do you deal with that? Compared, for example, with shooting in Eastern Europe, do you find yourself to be more judgmental or critical with regard to Japan?

TY: It’s impossible for me to be objective with Japan, or at least my thoughts spill out before they are fully formed. At the same time I don’t want Japanese to be seen only as nationalists; in my new works I am reconsidering what it means to be Japanese. Following the Meiji Restoration Japan turned toward authoritarianism, and even if this could be strategically justified by the desire to stand shoulder to shoulder with the West, I have no intent of whitewashing what happened. I believe that the distortions of that period are connected to what happened in Fukushima. Disregarding the fact that we were the first country in the world to suffer a nuclear strike, the entrapment of the people who in the 1950s were seduced and manipulated by the idea of applying nuclear energy for peaceful purposes extends into the present.

I hope to make works that can address major aspects of Japan including such issues. For example, I have made some new photographs of chrysanthemum flowers, which as a symbol of the imperial family appear on the cover of Japanese passports, even though one would assume that the national symbol should be the Hinomaru “rising sun” of the national flag. The flower in that sense symbolizes the ambivalence of the Japanese people. I’m not photographing the flower as a symbol of the imperial family. I’m photographing it as a portrait of Japanese people today.

Top: Heian Shrine I, Kyoto (Sorge & Ozaki) (2008), gelatin silver print, 9.5 x 9.5 cm. Bottom: River – View of earthquake regeneration housing project from a river flowing through a former location of evacuees’ temporary accommodation (2004), C-type print, 76 x 96 cm.

ART iT: Do you think the works you have shot in Japan will receive different responses from those you have done so far?

TY: Right now I have no expectations. I’m sure there will be unexpected responses. For example, the issues with Yasukuni Shrine are something we as Japanese people are unable to avoid. Even in Europe it’s a topic that comes up every year in the media, and something I have been constantly thinking about. It’s not necessarily that I want my works to have some political significance, but they could be considered a statement of my hopes for bringing about an age of peace. Beyond whatever political associations the image itself will elicit, I hope that through it people can also visualize the relations between image and memory.

The point of origin for this thinking is perhaps my parents’ experiences of World War II, which form a powerful axis for thinking about the past and present. Osamu Tezuka’s manga series Adolf (1983-85) was set in Kobe [events in the story, about a Japanese-German man and Ashkenazi Jewish man both named Adolf, and their connection to Hitler himself, begin in 1936], and the line, “Akashi is burning,” evokes the stories my father told me of that time.

ART iT: Speaking of which, how do you now view the work “A Decade After,” with photographs of areas struck by the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake?

TY: I am from the area, born in Akashi. As the bigger city, Kobe was always the place my friends and I went to for hanging out. Wanting to preserve that memory for myself, I shot photographs of areas we used to frequent, in black-and-white. This was about three months or so after the earthquake; I was abroad but had returned home because I was worried about my parents. Without ever publishing the photos, I put them away. Then in 2003 when I had my solo exhibition at Shiseido Gallery, I met a curator from the Ashiya City Museum of Art and History who was planning an exhibition revisiting the earthquake 10 years later. This curator was interested in me as an artist from the Kansai region who lives abroad and might be able to photograph the area from a more objective viewpoint than locally based artists, and so asked me to make photographs of the current situation, to be paired with the older photographs I had made.

At the time, as with my other works to date, I wanted to capture those things that are invisible or not immediately apparent – to make visible those invisible distortions. For example, in the middle of some area built like a housing exhibit with new homes all constructed to the same specifications, you might find a vacant lot, and feel some peculiar sensation. Then, asking around, you would learn that the lot was owned by a family that died in the earthquake, and is still caught up in estate settlement.

The photograph River – View of Earthquake Regeneration Housing Project from a river flowing through a former location of evacuees’ temporary accommodation, Japan (2004) was shot overlooking a river that once had temporary housing lined up along its banks, beyond which in the distance now rise earthquake regeneration housing projects built by the city of Kobe. It’s not visible, but what I wanted to photograph was the fact that even a decade later, there were still people with psychological scars from the earthquake. At the time I was aware that, as though left to rot, the people who lived in temporary shelters had been placed in a considerably remote area, and experienced a high rate of suicide. But then when I was shooting my photo the young boy entered the frame. Seeing him, I felt that even with all these serious issues, just as the boy had grown, so too could there be room for a small hope, or at least a beacon toward the future, and that was when I released the shutter.

ART iT: Have you revisited “A Decade After” since March 11? Certainly there are overlaps between the Hanshin and Tohoku earthquakes. On the other hand, since you seem to prefer viewing things from a distance, do you need more time to allow some distance from which to consider March 11?

TY: Yes, there are overlaps. But with March 11, there is the Fukushima nuclear crisis, so I also think of “Scene” in addition to “A Decade After.” However, in making my new works, I think it’s fine not to have so much distance from Fukushima, because the problems there are a continuation of those that began in the Meiji era.

Heat I (1996), gelatin silver print, 47.5 x 37.5 cm.

ART iT: Finally, many of your works have documentary elements, but would you consider mixing fiction into them?

TY: “Topographical Analogy” was a kind of fiction for me. But once I understood the specificity of places, or the unique power that places have, I decided fiction was no longer necessary and got rid of it from my practice. That was the beginning of the objective approach that I continue even now. Earlier you asked about how I fit all my research into one image, and it was difficult for me to explain, but there is a part that is not constructed. There are different circumstances each time that make everything open to chance, but being able to identify that point you want to capture is about knowledge gained from experience.

Return to Index

Tomoko Yoneda: The Multiple Lives of Images