II. Antonino’s Bundle

Dayanita Singh on photo editing, form and dissemination.

From the series “Dream Villa” (2010). All images: © and courtesy Dayanita Singh.

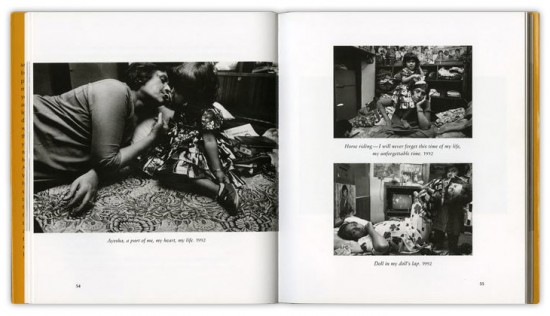

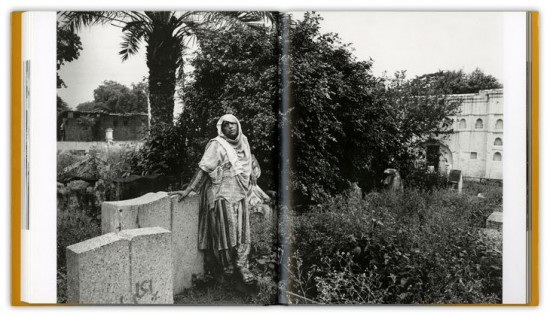

ART iT: We were just discussing photography in terms of breakdown, and how your images change significance depending on who is viewing them or who you are addressing. One thing that I noticed with your color photography is that it resists the idea of the photo as an absolute index, in that your photos “index too much.” For example, in House of Love (2011) there’s a nightscape of the city, with all the lights in the apartments, and the viewer is confronted with all the individual lives represented by each light. There’s no single focus, particularly because of your rejection of the photo-journalistic caption. And through your use of daylight film at night, even with the simple image of a tree, the colors are so heightened and outlines so blurred that it is no longer only an image of a tree. Yet this sense of indexing too much is something that already seems to be nascent in early works like Myself Mona Ahmed (2001), with its portrayal of how the titular Mona’s agency and place in the world, already tenuous because she is a eunuch, are thrown out of balance when her daughter Ayesha is taken away from her. Mona has multiple identities throughout the course of the book.

DS: Mona was really about what it means to be alone. It’s unfortunate that the book always gets pegged as “gender” and “eunuch” and all that. In that sense the book has been a failure, because it’s a story about alienation at its height. First you join the eunuch community and you’re alienated, and then you’re thrown out from there, so you’re outcast among the outcasts. I had hoped the conversation around it would be about loneliness, but that never happened. I guess the curiosity factor always takes over.

Curiosity is a key word in how I now edit my photos, because I don’t want to make pictures to satisfy anyone’s curiosity. I’m not going to tell you about what a certain situation is like. That’s why the night is my medium, because it removes all context. And then I’m using daylight film, so that even the night is not quite as you see it. I want to disorient you, and if you’re getting too comfortable in the sequence of the book, I want to turn you over a bit.

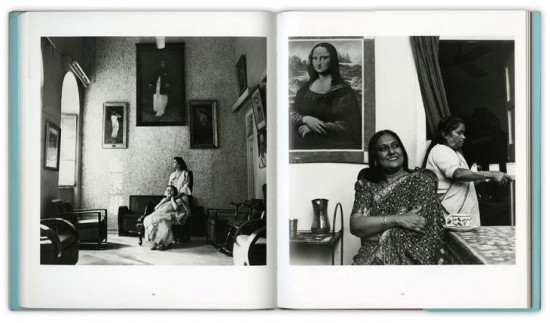

Both: Spread from Myself Mona Ahmed (Scalo, 2001), hardcover, 176 pages, 20.3 x 17.8 cm.

ART iT: How does that sensibility relate to the form that your books take?

DS: Well, I think Mona needs a new form. Beautiful as the book is, it just becomes this gender story, and that would have been so easy to do and so marketable: everyone’s dying to hear the true hijra story – I hate that word, I can’t even believe I just said it. It’s the same thing with prostitutes. You could spend your lifetime photographing prostitutes because it’s the sexiest story ever.

So the Mona story just failed really. I’m experimenting with the idea of a new version for projection, something I already tried out with the Dream Villa Slideshow (2010) at Venice and in the exhibition “Where Three Dreams Cross” at Fotomuseum Winterthur before that. I’m interested in projections because now that I have to scan my images to make the prints, what’s the point of making prints?

Or I wonder if Mona’s story needs to be text only. Why does it need to have these photographs? Maybe it could be only six photographs. If someone were to spend time with Mona, I think they would find her story is far more important than the pictures. Just last week in Delhi, I gave a grant of a hundred rolls of film and processing to a young photographer in Mona’s name. Mona’s not well, she couldn’t attend the ceremony, but she sent a beautiful message over the phone for the photographer, which I read to the audience: “Everything will pass, our childhood goes, my youth has gone, but in my photographs I live forever, may Allah guide you through this photo life. Myself, Mona Ahmed.” She’s very wise, and I think perhaps the photographs do a disservice to that wisdom. When she talks about English love and Hindustani love, that’s a whole chapter to be written. She has the wisdom, but I wasn’t able to ask her to explore that direction further. Somehow I feel the Mona story has not yet reached its true format.

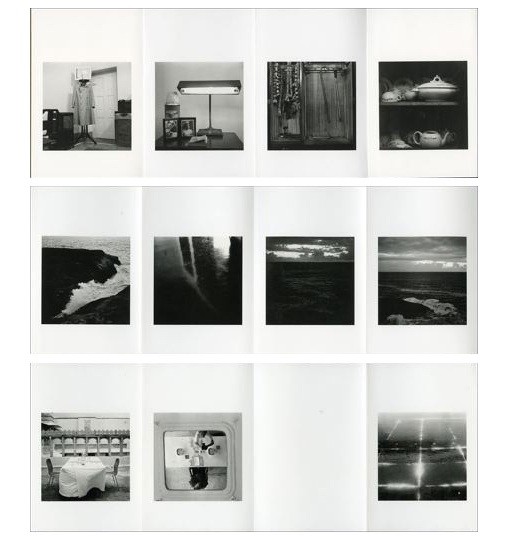

Sent a Letter (Steidl, 2008), 7 volumes, softcover, housed in a handmade cloth box, 126 pages, 9 x 15 cm each.

ART iT: If the books have this provisional aspect of seeking out their true formats, is there much calculation involved when you are actually shooting and composing images?

DS: No, that calculation is very dangerous. The shooting part I feel has to be very intuitive, although it’s also informed by conversations with the outside voices, and the books you’re reading, and the music you’re listening to. Go Away Closer (2007) was made from reediting all past work, but I recognized the emotion I felt while doing that, and built upon it in new works. Now with House of Love it’s this nighttime disorientation mode. It’s not that I’m looking for anything specific; everything just falls into place.

This also happens with the addressee. Sent a Letter (2008) is a great example of how the books change depending on for whom they are made. If I want to make a book for someone from my experience of Tokyo, it would be completely different than if I just set out to photograph Tokyo. At that point I’m not thinking about the words we associate with photography, not at all.

For me making the photo is maybe 10 percent of my work, or even less. It’s the form that it’s going to get that is where most of the time is spent. The timeline begins with making the photographs, then there’s a big gap before the weeding out, and then the editing starts, and you put the photos in different clusters, and then there’s the sequencing, and then there’s the pacing, for which music is really crucial in how it turns out. Then the form starts: Will it be a projection? Will it be a book? Will it be printed on napkins, so you get a box and take out image after image, wipe your hands with it and throw it away?

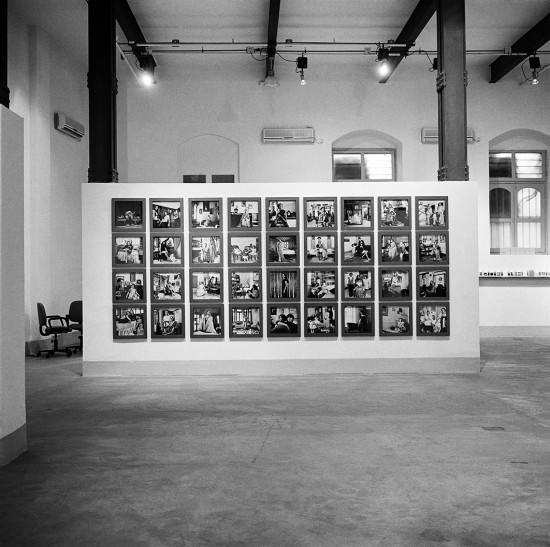

Top: Installation view of Sent a Letter on display at Satramdas Dhalamal Jewellers, Park Street, Calcutta (2008- ). Bottom: Installation view of the exhibition “Ladies of Calcutta,” Bose Pacia Gallery, Calcutta, 2008.

ART iT: You mention the addressee, and this idea with the napkins of a disposable photobook. I’m fascinated by this aspect of your practice, not just with something like Sent a Letter, but also with the exhibition of portraits held at Bose Pacia gallery in Calcutta in 2008, “Ladies of Calcutta,” where all the people who sat for the portraits took them home from the gallery.

DS: I always give prints to the people I photograph. I made those portraits in 1996-98, and I gave prints to the sitters at that time. We would decide on the final print together, and in those days I didn’t think about value, so there are people who have something like 20 work prints of my photographs, from which they chose the final. But I guess because they were shy, they never put the prints up in their homes. Then with the exhibition I framed the new prints in very thick frames and presented them to the sitters unpacked: everything was done so that they had to put it on a nail. It was framed, so they couldn’t put it under a mattress, and it was unpacked, so they couldn’t leave it in the packing, and now the prints are hanging in 66 homes in Calcutta.

At the same time in January 2008 I also put Sent a Letter on display in the window of a jewelry store in Calcutta, on Park Street. It’s still there. It’s like having an exhibition for three years in the Shiseido show window. Even if only one percent of the passersby see the work, it adds up to more numbers than any museum.

I love that aspect of photography – the dissemination of it – and that has to do with having been a photojournalist, because you know how many people see your images and think about them. The keys for me are dissemination and giving. I love my books and I feel they are a gift, even when you buy them. I feel in making the book I’ve given you a gift, so I want you to buy it, but I think people don’t give enough importance to that, so now I am designing my own book cart, like a dim sum trolley, with three levels. The top level will have Sent a Letter, the middle House of Love, and below that the big Dayanita Singh (2010) book, just because of the essays in it by Sunil Khilnani and Aveek Sen. I’m having a cart made in Goa out of stainless steel, and one made in Delhi out of wood, and I’m making one here in Tokyo, because I think I’ll get the best wheels here. And I can take these carts around to different events and openings. I always think of the books themselves as my work.

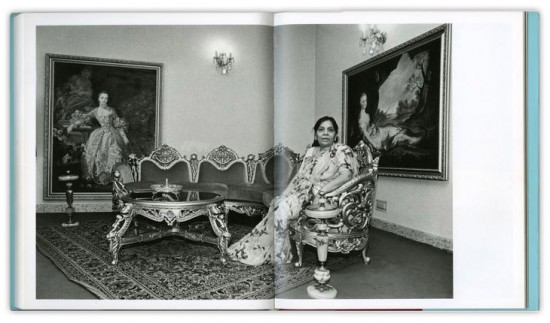

Both: Spread from Privacy (Steidl, 2004), clothbound hardcover, dust jacket, 128 pages, 90 tritone plates, 20 x 24 cm.

ART iT: But the dissemination of gifts can also be ambivalent, as with the book Privacy (2004). These are portraits of people who in some cases seem quite interested in projecting their social status to the camera. It’s tempting to view the work as both a celebration of material traditions and a critique of bourgeois pretension, but impossible to decide for either, because there is a contradiction between the intimacy of the access and the exposure of the resulting image.

DS: Absolutely. After that I started “Empty Spaces.” I’m very cautious now working with people.

Privacy was part of a process. It was at the time the only way to get away from photojournalism. I thought that at least I could photograph families and if nothing else they could hang the pictures in their homes. It was not intended for publication, because nobody was interested in the work, except the families. Then somehow Robert Frank heard about it and sent me a huge grant. Otherwise it would have been too expensive to shoot, and on top of that give prints to the people.

If I had to be critical of my work, I would say it really started to form with Go Away Closer, and everything else was a preparation for that. In a way up to that point I had exposed my student work. From Zakir Hussain (1986) to Myself Mona Ahmed, Privacy and Chairs (2005): something really opened up with Go Away Closer.

Now in House of Love I see similar elements, but it will also become something else, and you can go mad from that. It’s like when you’re tumbling down a mountain and you don’t know where it’s all going to crash. Storytelling I guess has been part of my language right from Zakir, but I don’t know which way it will go from House of Love, and actually I don’t want to know. And the day I know will be the day to stop; then I can start gardening or whatever. I’m not interested in the end product. It’s the somersaults. I’m interested in the tumbles and what comes after that. I think it will finally take me out of photography. I’ll still be photographing, but somehow having escaped from photography.

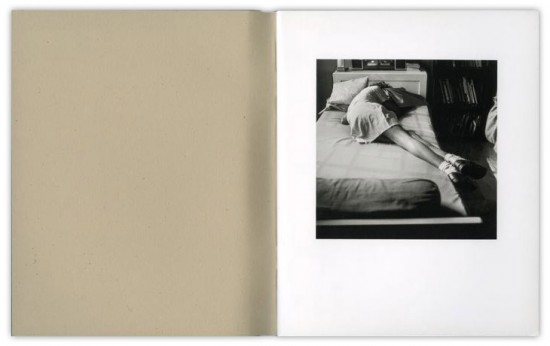

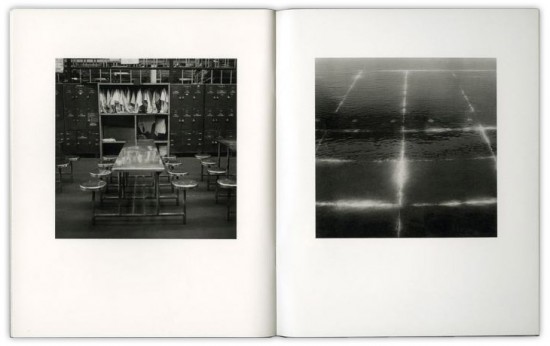

Both: Spread from Go Away Closer (Steidl, 2007), softcover, 32 pages, 31 tritone plates, 16 x 20 cm.

ART iT: Of course the title Go Away Closer itself is a contradiction.

DS: That’s love. Isn’t that what happens between parents and children? I’m sure that as much as they love them, parents must sometimes wish they could get away from their children, and yet couldn’t imagine living without them. And as children, we love our parents but can’t bear to be with them either.

To me that’s photography. You’re trying to hold onto something but in the process of trying to hold onto it you’re pushing it away. In any case life has already pushed it away, because it’s over. That contradiction is key to me. If I had to make a book of my life’s work, “Adventures of a Photographer” would finally be called Go Away Closer.

Return to Index

Dayanita Singh: The Always Exceptional Condition of Images