Painter and ‘counterfeiter’ – On ‘Makoto Aida: Monument for Nothing’ (Part 1)

Installation view of “Aida Makoto: Monument for Nothing” at the Mori Art Museum. Courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery. Photo Osamu Watanabe, courtesy Mori Art Museum.

The exhibition “Makoto Aida: Monument for Nothing” at the Mori Art Museum (Roppongi, Tokyo) has attracted a lot of attention for various reasons. I saw the exhibition last year, and was greatly intrigued both by the extensive collection of existing works and the new works. At the same time, however, I had more than a few doubts about the initial response, which to my ears consisted of nothing but praise for the artist.

Makoto Aida has been dubbed among other things a “venomous artist” on account of his style, and in regards to the realization of this exhibition, too, I have heard that there are no plans to take it to other museums and that the desired level of corporate sponsorship was not forthcoming. Given this “uphill battle,” the efforts of the Mori Art Museum in working together as one to pull off a Makoto Aida exhibition are worthy of close attention. So why, then, the doubts? The reason relates to the “venom” touched on above.

But what do we actually mean when we talk of “Makoto Aida’s venom”? We will touch on this in due course, but for the present, let us consider the following. If Makoto Aida really were a “venomous artist,” it would be unthinkable for there not to be intense debate or for questions about him not to be raised while the exhibition was on. Alternatively, if no fuss were to occur at all, surely this would mean that Makoto Aida was not venomous to begin with. Ultimately, one could only conclude that Makoto Aida is a harmless artist, in which case the “decisive action” of the art museum, which simply held an exhibition by a “wholesome” artist, would naturally lose much of its significance.

So what actually happened? At the very least, around the time I visited the exhibition, it was attracting nothing but praise from art insiders, culturati and the like. In other words, circumstances were extremely close to the latter scenario. Perhaps this is the reason the exhibition failed to rank among my list of “the best four of the year” published in a major newspaper at the end of each year despite being among the best exhibitions of 2012. It was as if in the gap between the provocative activities Makoto Aida the artist has engaged in over the last 20 years, ironically ridiculing the “art” of prize pupils and the bland compliments he has received, one could glimpse the social “defeat” (although not the surrender) of an artist who has referred to himself as a “lifelong kawarakojiki” (literally, “riverbed beggar,” a derogatory term once applied to actors) painter. (1)

As the new year began, however, the criticism directed at the exhibition suddenly intensified. For the reasons given earlier, however, I basically “welcome” this series of “ructions.” This is because I think that in each case the true nature of Makoto Aida the artist, the merits of the Mori Art Museum and so on have clearly been questioned.

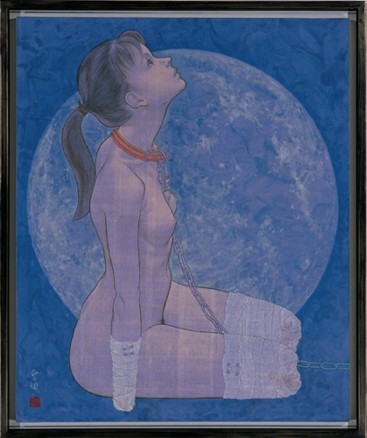

Broadly speaking, this criticism can be divided into two categories. The first relates to the suspicions of “child pornography” directed mainly towards the series of works depicting “pretty young girls” with their arms and legs amputated as “dogs,” while the second relates to the suspicions of “copyright infringement” directed towards Monument for Nothing IV, in which Aida borrowed without permission and collaged hundreds of tweets by others on Twitter. To reiterate, these are far from trivial complaints. This is because depictions of a sexual nature and the use of appropriation are images and a technique central to Makoto Aida’s practice, which he has employed freely since the start of his career. Naturally, the onus is on the Mori Art Museum to present to the public logical arguments in support of Makoto Aida and his artwork.

Aida Makoto – Dog (Moon) (1996), mineral pigments and acrylic on Japanese paper and board, 100 × 90 cm. Takahashi Collection, Tokyo. Courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery.

Aida Makoto – Monument for Nothing IV (2012), acrylic, paper, plywood, wood bolts, 570 × 570 cm. Courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery. Photo Osamu Watanabe, courtesy Mori Art Museum.

It goes without saying that the starting points for such an undertaking are above all the commentaries and analyses regarding Makoto Aida and his artwork published in the exhibition catalog. Among these, the main text by the chief curator responsible for the exhibition (Mami Kataoka) plays an important role. However, upon rereading this text following the surfacing of the various issues touched on above, I noticed that any consideration of the two subjects that are both difficult to avoid and need to be addressed when discussing Makoto Aida, that is, “sex” and “appropriation,” is crucially absent.

With regard to the former, there is hardly any reference to it at all, while with regard to the latter, it is considerably trivialized by naively linking it to the pre-modern (ie, pre-capitalist) Japanese practice of honkadori (adaptation of famous poems) while at the same time employing the terms “sampling” and “remixing” as suggested in my book Simulationism (1991) (although no reference is made at all to the book). Given this, from the outset I held no hope of those responsible having the staying power and so on required to respond to the various issues that one might have expected to have been and were in fact raised. Returning to the main text, not only does it include passages very similar to logical arguments in chapters 3-4 of another of my books, Nihon/Gendai/Bijutsu (Japan/Contemporary/Art, 1998), again without any reference, but by blandly referring to the identifying characteristic of 1990s art, which I identified as “schizophrenic,” as simply “chaos,” it severely narrows the scope of the issue. (2)

If Makoto Aida were indeed a “venomous artist,” then it would be natural and predictable that issues concerning his depiction of sex and copyright would arise while the exhibition was on. To respond to these issues as Kataoka’s essay does by explaining that “Makoto Aida is a man of chaos” (“Sorry for being chaotic”?), for example, has no potency whatsoever as far as others are concerned. What is more, Makoto Aida is certainly not a “man of chaos” or anything of the sort. This cannot be emphasized strongly or often enough. With this in mind, I would like to trace Makoto Aida’s career back to its starting point.

Makoto Aida’s “debut” as an artist was at the “Fortunes” exhibition (Roentgenwerke, curated by Min Nishihara (3), 1993). Even at this early stage, Aida made a point of mentioning his seemingly jumbled style, referring to it using the phrase “iroiro na dezain” (“various designs”). It need scarcely be mentioned that this is an adaptation of “Samazama naru isho” (Various Designs), the 1929 essay that marked the literary debut of the critic Hideo Kobayashi, who had a major influence on Aida. In this way, Makoto Aida intentionally incorporated into his own lineage as an artist a design element in the form of “Hideo Kobayashi.” In short, unifying the multiformity of Aida’s work, which on the surface cannot help but appear “chaotic,” is without doubt “criticism as design.” Or to put it another way, based on his own experience as a “painter” “setting out” as a “critic of painting,” a process of fragmentation and coexistence in which he was required to abandon himself, Aida astutely observed of the circumstances of art at the time, which had degenerated into a jumble of “various designs,” including every genre from Nihonga, Western-style painting, illustration and manga to anime, or in terms of contemporary art from abstract expressionism to minimalism, from Mono-ha to post-Mono-ha, that it in fact constituted “various ‘artless’ designs.”

While casting a sober eye over the “various designs” concerning literature, Hideo Kobayashi was at the same time plainly aware of the contradiction represented by the fact that the only way to share his own critical passion was to write about “design” in some form or another. Similarly, notwithstanding the distorted critical spirit he adopted towards what he saw as an absence of art, Aida must have been thoroughly aware that his own expression would inevitably have to “be expressed” as some form of “simulacrum.” Today, however, when capitalism has developed to an extent incomparable with Kobayashi’s time, on each occasion these designs must inevitably turn into “various designs” that one is compelled to choose (ie, consume). While knowing this, Makoto Aida took it upon himself to flatten and borrow the “appeal” of everything from “substantial oil paintings” to “delicate Nihonga,” from “vulgar graffiti” to “illustrations bordering on pornography,” turning them into the art equivalent of “paper tigers.” From Aida’s perspective, in unfortunate times in which the “various designs” originating from Hideo Kobayashi and “simulationism” must inevitably come together, this was the only form “bad art” could take.

To put it plainly, Makoto Aida’s “Nihonga” and “oil paintings,” his “manga” and “installations,” lack “appeal” as Nihonga and oil paintings, as manga and installations. It is probably for this very reason that he staked the very limits of his abilities as an artist on the “counterfeiter” (André Gide) as an “image” with which to present himself to the public. It is in this context that one should understand his reference to himself as a “genius,” in which case it is clear that he is in fact apologizing (“sorry”) for the hidden “hypocrisy” (as opposed to the pretence of evil) this entails. With regard to the suspicions of “child pornography” and “copyright infringement,” too, ultimately it behooves us to respond based on the twisted nature surrounding Makoto Aida the artist without being distracted by the particulars of legal interpretations. (To be continued)

“Aida Makoto: Monument for Nothing” ran from November 17, 2012 to March 31, 2013 at the Mori Art Museum.

-

- See the trialogue involving Makoto Aida published in

Ato no shigoto

-

- (The Work of Art) (Taiyo Lecture Book 004, Heibonsha, 2005).

- Regarding this matter, even if the various issues that surfaced during the exhibition were “unforeseen” (and all the more so if this were in fact the case), this does not alter the fact that issues like “sex” and “appropriation” touch on values with respect to art today that need to be questioned. Rather than brushing aside these issues, the chief curator, Mami Kataoka, should open up the debate to society by actively holding press conferences and so on. This is nothing less than a watershed, one possible outcome of which is that at the end of the exhibition not only the attitude of the art museum but also the “venom” of Makoto Aida the artist is able to be ignored as “a source of trouble,” the other that Aida is recognized as an artist raising issues worthy of serious consideration. It demands a serious response from Kataoka as the curator.

- For the record, let me state clearly that it was Min Nishihara, like Aida a graduate of Tokyo University of the Arts and then an art critic, who “discovered” Makoto Aida as an artist.