A Restatement: The Art of ‘Ground Zero’ (Part 5)

Iwaki Yumoto III

On March 21 of this year I flew to Hakata with the artist Takashi Murakami. We went there to visit the artist Mokuma Kikuhata. As soon as we landed we made our way to the Fukuoka Art Museum, from where, together with the curator who had arranged our meeting, we headed off to Kikuhata’s residence, which doubles as his atelier.

It was my first meeting with Kikuhata. And yet he is someone to whom I am greatly indebted. For it was my encounter with a collection of Kikuhata’s writings published by Kaichosha, Ekaki to senso (Painters and War), that originally got me interested in “war paintings,” which have long been one of the main focuses of my criticism. Indeed, it is unlikely that either my first foray into this subject, Nihon-gendai-bijutsu (Japan-Contemporary-Art) (1998, Shinchosha), or the concept of Japan as “a bad place” that I arrived at in the course of writing it, would have come about if not for my reading Kikuhata’s book. Certainly as an artist, but also as a writer, Kikuhata is an incredibly important figure in my life.

For his part, Kikuhata greeted us with a smile, saying, “I’ve wanted to meet you for some time. But I just haven’t had the opportunity.” Kikuhata had previously contributed an article to the periodical AIDA (No. 116) that was extremely supportive of my book Senso to banpaku (World Wars and World Fairs, 2005, Bijutsu Shuppansha), a sequel of sorts to Nihon-gendai-bijutsu. Anyway, we sat there in front of Harukaze (2011), a recent, large painting by Kikuhata that dominates his atelier (it is a phenomenal work that combines an emanation of youthful energy beyond all expectations with a coolheaded materiality), and listened as the artist offered valuable insights on a range of topics.

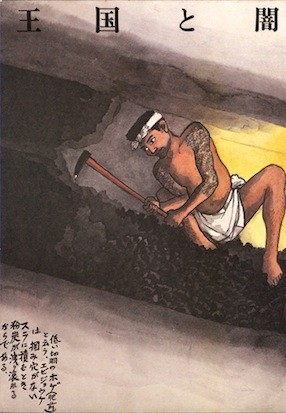

Cover of Okoku to yami (The Kingdom and Darkness) (1981, Ashi Shobo), a collection of works by Sakubei Yamamoto.

The content of our discussions I will have to return to on another occasion, because what I would like to touch upon here is the series of “coalmining paintings” (as opposed to “war paintings”) by the Fukuoka-born artist Sakubei Yamamoto (1892-1984) that depict the harsh working and living conditions faced by coalminers in Chikuho, paintings that were last year included in UNESCO’s Memory of the World register of documentary heritage. Sakubei, who worked in the coalmines from the age of seven, retired as a coalminer at the age of 63 and became a security guard at the coalmine office, whereupon he began to produce – with no instruction whatsoever – paintings based on his own memory and the meticulous records he kept in the form of diaries, amassing a collection of over 1000 works by the time of his death at the age of 92.

In fact, Sakubei’s paintings, which are so widely known today, were not in the spotlight from the very beginning. They only came to the attention of the world at large due to the activities of none other than Mokuma Kikuhata, who tirelessly introduced and publicized them. In particular, he contributed his own lengthy criticism for a collection of works by Sakubei titled Okoku to yami (The Kingdom and Darkness) (1981, Ashi Shobo). The printing of this publication, with which Kikuhata was so closely involved he is said to have checked the color proofs himself, is astonishingly clear, with attention paid to even the smallest detail. Looking at this work, a large-format, boxed edition, which should perhaps be regarded as an artist’s multiple, the image of another coalmine artist I met in Iwaki Yumoto crossed my mind.

Earlier in this series I noted how the history of the Joban region – while once serving as an important energy supply base due to its possession of so many coalmines spread over such a wide area so close to the metropolitan area, and as a major coalmining labor center on a par with the likes of Yubari and Chikuho – had somehow been wiped from our memories. At the same time, this same region has a close association with hot springs, so much so that when someone mentions “Joban” we immediately think of the Joban Hawaiian Center. This in spite of the fact that the construction of this facility was the result of locals creating a tourism industry based on the hot springs that had existed since long ago out of necessity after one mining operation after another was forced to shut down in the wake of major changes in the course of the country’s energy policy since the 1950s and the liberalization of energy imports.

It was in the course of making trips to and from Iwaki Yumoto that I first understood how indescribably harsh conditions were for those working in the coalmines there. At the same time, I learned how the coalmining industry in Iwaki Yumoto was in a “battle” with the region’s hot springs, which in normal circumstances would be regarded as a blessing. Here, the word “battle” has a double meaning. First, the hot springs were so plentiful that extracting coal in Iwaki Yumoto involved a battle with constantly spouting hot water. And second, conflict arose with the hot spring resorts, several of which operated in the area. Due to the coalmining operations, which started in the middle of the Meiji period, the amount of hot water welling up fell dramatically, with large amounts of hot water that otherwise would have impeded mining being drawn up and dumped (at the rate of 14 tons a minute) in rivers, as a result of which the water temperature near the outfall in the Shin River that flows through what was then Uchigo City reached 46 degrees, turning the river itself into one huge open-air bath and destroying the balance of the inns with hot spring facilities. (To digress a little, in considering this latest nuclear accident, it is worth bearing in mind that the whole area from Kitaibaraki to Hamadori in Fukushima Prefecture contains a massive coalfield that extends all the way to the Pacific Ocean, as well as huge reserves of underground water. If a nuclear fuel assembly were to melt and contaminate this underground water, even if a phreatic explosion were not to occur, it is clear that the result would be water pollution both on a scale beyond anything we could imagine and from which it would be impossible to recover.)

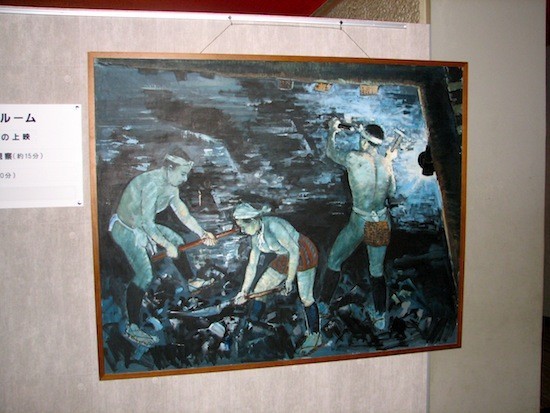

Shoveling coal (c. 1944). Mineshaft diorama at the Iwaki City Coal and Fossil Museum. Photo courtesy the Museum.

The Iwaki City Coal and Fossil Museum in Iwaki Yumoto is a good source of information about these and other developments in the coalmining industry as it pertains to the Joban region. In particular, the extensive underground displays including dioramas that recreate working conditions in the coalmines at the time are worth seeing. Working in the mines was also a relentless battle against things like invisible toxic gasses and punishing humidity, and looking at the exhibits of the detection equipment, gas masks, and so on that were used to combat these dangers, the similarities between working conditions in the coalmining industry and in the nuclear industry become obvious.

Might there have been something similar to the paintings Sakubei Yamamoto produced in Chikuho in the Joban region, which must contend with these peculiar circumstances? Of course, there were. They were not produced by a single person, however. And while they do not have their own exhibition facility, we can view these paintings at the Iwaki City Coal and Fossil Museum mentioned above. Mind you, perhaps because they are difficult to classify, these paintings seem to lack a place of their own, and are hung here and there in places like stairway landings, passageways, and exits. And yet artists like Taro Kumasaka (1910-92), who was born in Fukushima and belonged to the art club while a student at Joban Junior High School, but who gave up the idea of going on to further education at art school in view of the family finances and found employment in a coalmine, where he worked in the security department while teaching himself how to paint, eventually exhibiting work in Tokyo, surely deserve renewed recognition at a time like this.

Taro Kumasaka – Kobansho (Shift Office). Photo courtesy Iwaki City Coal and Fossil Museum.

Taro Kumasaka – Tankozu (Coalmine Picture). Photo courtesy Iwaki City Coal and Fossil Museum.

In 1941, while still employed at the coalmine, he tasted success for the first time when his painting Tanko fukei (Coalmine Scene) was accepted for the 28th Nika Exhibition. He was accepted numerous times in the years that followed, with G tanko no ichigu (One Corner of Coalmine G) (1947, 34th Nika Exhibition), Tanko shayo (Setting Sun at a Coalmine) (1949, 4th Kodo Exhibition), and Tanko no fukei (Scene at a Coalmine) (1956, 1st Shinseiki Exhibition), and even after retiring in 1963 he continued to paint locally. It would be true to say that he gained a certain level of recognition in art circles even when he was still alive, but while his paintings lack the singular originality of those of Sakubei Yamamoto, this does not alter the fact that they are a valuable resource in gaining a renewed appreciation through art of the origins of the circumstances we find ourselves in today. (To be continued)