Obscenity as a symbol – Rokudenashiko and Genpei Akasegawa

Rokudenashiko in her “Manboat.” Photo courtesy Shinjuku Ophthalmologist Gallery

Artist Rokudenashiko has been rearrested. (1) As with her first arrest in July 2014, this latest action stems from suspicions on the part of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department’s Public Security Bureau that artworks that use her own genitalia as a motif amount to “obscenity.” This is an extremely unusual situation. By this I am referring to the fact that the suspicions that formed the basis for her original arrest were similar in content to those that formed the basis for her rearrest. On that first occasion her attorney’s quasi-appeal against the decision to detain her was accepted, as a result of which Rokudenashiko was released. In other words, it was accepted that she was unlikely to flee or destroy evidence. It makes no sense that she has been rearrested on the basis of the same suspicions.

Although I referred above to the suspicions being “similar,” strictly speaking they are not exactly the same. In July she was arrested on suspicion of “emailing the URL to which 3D data of her own genitalia had been uploaded (distribution of an obscene electromagnetic recording medium),” but this time the address to which she allegedly sent the data is different. Even if true, it is difficult to believe that this alone is a justifiable reason to detain her. Perhaps this is why in addition to this the police put forward another suspicion different from last time as the reason. This is the suspicion of “displaying in an adult shop an ‘obscene object’ in the form of a colored mold of her own genitalia (display of an obscene object),” which led to the owner of the shop, writer Minori Kitahara, also being arrested.

However, even if one were to accept that the suspicion of transmitting data might lead to an “obscenity” due to the ability to reproduce female genitalia faithfully using the latest technology, one senses no such reproducibility at all in the latter “artwork.” In addition, it was displayed not in a public place but in an “adult shop” where it was visible only to customers who had a personal interest in it to begin with, a place whose public nature is minimal compared to the street or an art museum, which is where such charges are most often brought (moreover the majority of these cases involve photographs). If “displaying” an object in the shaped of genitalia – regardless of whether it is male or female – in an adult shop amounts to a crime, then surely the owners of the countless other similar shops should all be arrested and detained.

Kitahara, who was arrested on suspicion of conspiring with Rokudenashiko, has already been released after the Tokyo District Court turned down the Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office’s request to detain her and remains at home while the investigation continues. As of now (December 22 [2014]), however, Rokudenashiko remains in detention, where she was initially subjected to the strictest conditions and prevented from meeting with anyone – including her family – other than her defense counsel. Although it now appears this prohibition on meetings has been lifted, one can only describe the continuation of her detention pending trial, albeit in the name of a rearrest, as beyond the bounds of common sense.

Below, however, I would like to share my views on this situation from a point of view somewhat different from such claims of injustice. This is because I got the sense that the response from fellow artists and others involved in the arts to the treatment of Rokudenashiko and her artwork has been strangely muted.

To come right to the point, I suspect that the reason for this is that even though they feel this case is unjustified, they do not see it as constituting “harm to a colleague” in the form of an artist. Here, “colleague” does not necessarily mean a personal acquaintance. Rather, I should perhaps have referred to people involved in the arts who “do not recognize Rokudenashiko as an artist,” which is to say people who “do not regard the things she makes as having any merit as artworks.” If someone is an “outsider” from the beginning, then it is only natural that the response to any injustice against them will be muted.

Well then, where does this (value) judgment by the art world that deems her an “outsider” come from? I can think of a number of sources. For a start, the pseudonym Rokudenashiko (meaning “good-for-nothing girl” or “bad girl”) is too “good for nothing” for a respectable artist to use (likewise, Chim↑Pom, whose artworks can now be found in the collections of the country’s national art museums, were for some time initially referred to as a “self-proclaimed artist collective” because, one assumes, their name sounds like a term used to describe male genitalia). Next, as evidenced by the artist’s own frequent use of the term manko (Japanese slang for vagina), for example, her treatment of the sexual organs is “lacking in character, flippant and lacking in artistic substance.” Finally, she works in the space between genres, principally as a manga artist, and her background is not in academism (ie, an art university – something that also applies to Chim↑Pom). There are no doubt other sources, but in any event, it is precisely because Rokudenashiko is seen as “failing to meet the required standards to be discussed as an artist” that, despite the fact that we are witnessing an extraordinary situation in which a creative is continuing to be held in custody without access to her friends or family because of her expression, to say nothing of the matter of freedom of expression, it is regarded as “someone else’s misfortune.”

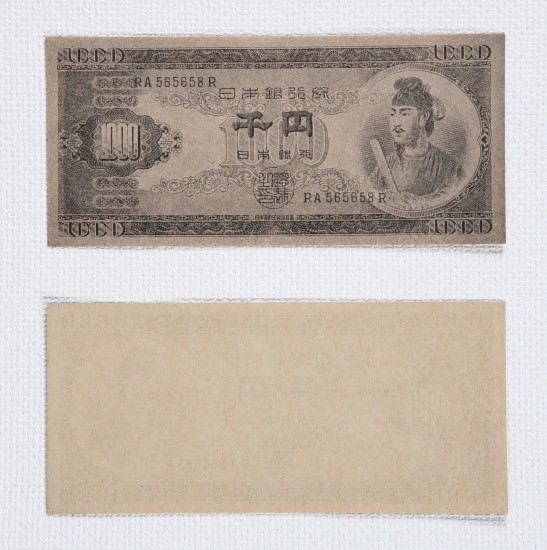

At the risk of being accused of jumping from one topic to another, I would like to remind readers that one of the most important events in the art world this year was the death of Genpei Akasegawa. In terms of his impact on the art world, Akasegawa is perhaps best remembered for the “thousand-yen bill incident,” which in the 1960s caused a stir not only in the art world but throughout Japanese society, and I cannot help feeling that there are in fact similarities between this latest incident involving Rokudenashiko and the “thousand-yen bill incident.” Below, I would like to explore this idea in detail.

Genpei Akasegawa – Model 1,000-Yen Notes IV (1963). Collection of the artist, provided by Shiraishi Contemporary Art, photo courtesy Chiba City Museum of Art

Firstly, the incident in which Akasegawa was arrested and tried for producing his own “fake thousand-yen notes,” with the guilty verdict ultimately being upheld by the Supreme Court, was no mere “common” counterfeiting incident (in fact, the judge himself recognized that the items in question were not counterfeit banknotes). Incidentally, while the reasoning behind the Tokyo High Court’s dismissal of the appeal against Akasegawa’s conviction can be read here [in Japanese], it would appear that the criminality implied in it is far more deeply rooted. In my opinion, faithfully reproducing a thousand-yen note and “displaying” it publicly, or “distributing” it by means of printing it, amounted to an act that from the point of view of the authorities could not be permitted under any circumstances in that it clearly exposed the hidden “source of embarrassment” of the state, by which I mean the simple fact that, although “when all is said and done,” banknotes are just scraps of paper, they prop up the entire state. In a manner of speaking, “obscene acts with symbolic meaning” amount to serious “thought crimes.”

In this respect, the difference between Akasegawa’s case and Rokudenashiko’s case is that the latter involves not scraps of paper but genitalia, not “a source of embarrassment as a symbol” but “a source of embarrassment as flesh and blood.” However, I cannot help thinking that with this latest incident, as was the case with Akasegawa, what is at play is the latent “fear” that something that has up to now been hidden as a source of embarrassment will be exposed again to the light of day, albeit in the form of “expression.” And just as Akasegawa’s fake thousand-yen note was a faithfully cast “reproduction” of a source of embarrassment (ie, a blind spot) for the state, Rokudenashiko’s “reproduction” of her own genitalia cannot help but make explicit the question, “For whom is the source of embarrassment a source of embarrassment?” a question that is after all extremely fundamental.

After all, Rokudenashiko’s genitalia are hers and no one else’s. This inevitably leads to the extremely basic question of why it must be regarded as a crime to either “display” (in a gallery in the case of Akasegawa, and in a shop in the case of Rokudenashiko) or “distribute” (in printed form in the case of Akasegawa, and in the form of electromagnetic data in the case of Rokudenashiko) something that is one’s own to begin with. I say this because for the purposes of maintaining the existing social order (a large part of which involves the subjugation of women by men), this question is one that must not be asked in public under any circumstances. But given that there were no actual victims and no immediate concern with respect to harm, the only option was to judge Rokudenashiko on the basis of the incredibly abstract notion of “obscenity,” and as was the case with Akasegawa, it was not even “obscenity as an example,” but “obscenity as a symbol.”

Contrary to the impression given by Rokudenashiko’s own artwork, appearance and behavior, this is by no means a light matter. To put it another way, perhaps it is precisely because of this attitude that the authorities have pursued her so relentlessly, including taking the unusual step of rearresting her, detaining her and preventing her from meeting her friends and family. This applies even if the police were not completely aware of it themselves – or rather, it applies precisely because they may have been unaware of it (ie, it is deeply internalized).

Given the above, one cannot say for certain that this dramatic arrest over “fake genitalia” that occurred in the same year that Genpei Akasegawa died and with Tokyo gearing up to host the 2020 Olympics will not eventually take on art-historical importance, in the same way that Akasegawa’s “fake thousand-yen note” has importance today. Or rather, as society becomes more and more open for future generations of women, the likelihood of this happening increases. And is not the arrival of such a world (one in which, in the words of the current administration’s own policy, “women shine”) something we are looking forward to? Art “insiders” who regard Rokudenashiko’s artworks and her “name” as “lacking any merit as ‘art'” and in the process reveal their own flippancy are simply ignorant of the fact that they are materially assisting those who would impede the arrival of such a “desirable future.” Or perhaps they have simply forgotten that prior to the “fake thousand-yen note” and serving as its starting points there existed Prophecy of a Patient (Glass Egg) and Sheets of Vagina (Second Present), two works by Akasegawa that deal with manko and expose the source of society’s embarrassment.

Genpei Akasegawa – Sheets of Vagina (Second Present) (1961/1994). Collection of the artist (entrusted to Nagoya City Art Museum), photo courtesy Chiba City Museum of Art

- The Japanese edition of this column was written December 22, 2014. Arrested on December 3, she was released on bail on December 26. Her trial began April 14, 2015 in Tokyo District Court.