INTIMATE BUT PUBLIC

A letter from Hou Hanru to Hans Ulrich Obrist

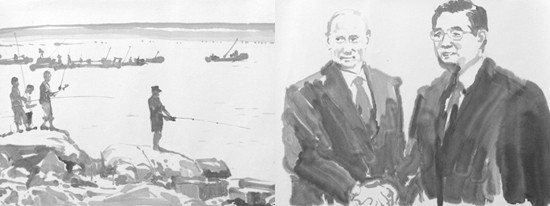

Sun Xun – Stills from The New China (2008), animation video, 15 min 19 sec. Courtesy the artist and ShanghArt.

Dear HUO,

Nice to read your latest contribution to our ongoing conversation in ART iT. Your A-to-Z list touches upon some of the most challenging and inspiring questions affecting today’s art scene, especially in terms of its relationship with a world that is rapidly changing due to globalization and advances in new technology. Your idea of “curating the world,” or curating as a toolbox for 21st-century society at large, is ambitious and attractive, while handwriting (and drawing) as a defense against the hegemony of the Internet in our lives and thoughts seems to be particularly relevant. I understand this as a very timely call for a return to real engagement on the parts of cultural producers – including artists and curators, as well as collectors and institutions – with cultural production and its ontological substance. It reminds us of the importance of the intimate link between what we are and what we do.

One of the latest discoveries for me in the exciting Chinese art scene is the emerging “movement” in video practice of hand-drawn animations, through which artists are seeking to construct personal and alternative narratives of “History,” reflecting a profound and dynamically imaginative desire to resist official versions of “Truth.” Chen Shaoxiong, Qiu Anxiong and, especially, Sun Xun are some of the most remarkable examples of this movement. On the other hand, at the San Francisco Art Institute I just opened an exhibition by Dan Perjovschi, who has covered the whole space with marker drawings and texts satirizing the contradictions in the logic of mass media through his unique and pungent exploration of puns of the “global media language.” Next to it, I’ve also exhibited On Kawara’s “Pure Consciousness” project with seven date paintings that traveled to 19 kindergartens around the world and were “shown” in the most intimate way at each site without any pedagogical impositions on the children.

Chen Shaoxiong – Stills from Ink Diary (2006), animation video, 3 min 55 sec. Courtesy Boers-Li Gallery.

This revisiting of intimacy alerts us to not forget what is the ultimate driving force for artistic creation. We are living in a time of global communication. Cultural products are inevitably commoditized and instrumentalized as media of social and economic exchange. Art is used increasingly as a materialized “aesthetics of relation” as well as a status symbol. In this light, now is the time for us to unequivocally embrace the personal and intimate relations between the artist and the artwork, relations that embody the eternal search for freedom of thought and expression, for dreams and even social utopias.

As curators, we are increasingly endowed with multiple roles in our professional and personal lives. We do not only conceive and realize exhibitions. More often, we are directly involved with all aspects of the evolution of the art world, the boundaries of which are incessantly expanding to cover all social fields – from cultural, social and political projects to urban transformation. Inevitably, we also have to negotiate the market’s increasing hegemony. Over the past decade, the focus of contemporary art events has been shifting from biennials to art fairs. Almost every major city in the world has founded its own art fair – often more than one. There is widespread confusion between artistic value and financial value.

This tendency is even more evident in Asia, where globalization leaves its strongest mark through economic booms and urbanization. The development of the art market in the region – merging “traditional galleries” and auction houses – is perhaps the most spectacular indicator of this process. And it is also the most visible sign of the confusion of values. We both somehow have to deal with this situation in our work. The recent third edition of the Art HK art fair in Hong Kong this May purports to have been a real success in terms of star power and business transactions. Mounting its fourth edition in Shanghai this September, ShContemporary is making all efforts to achieve even greater success. Interestingly, you attended the former as a speaker as part of the fair’s educational programming, while I’m currently organizing a forum on collecting Asian contemporary art for public institutions at the latter. Ironically, we find ourselves in a kind of “intimate” relationship with the market.

Installation view of “Dan Perjovschi: The Institute Drawing” at the Walter and McBean Galleries, San Francisco Art Institute, 2010. Courtesy SFAI.

Behind the spectacle of financial speculation and fame seeking, this “market turn” in artistic production and socialization represents some of the most exciting and complex histories of contemporary social and cultural innovations driven by experimental economic and political developments. However, we often tend to forget that Asian contemporary art’s global success is driven by its intimate relationship with local histories and contexts. Asia, a highly complex and diverse continent, has undergone the most amazing process of modernization over the past few decades, and the artistic productions of this period to a great extent embody this major historical change. In the process hundreds of artists, from highly personal and diverse approaches, have struggled for freedom of imagination and expression alongside their contemporaries in the intellectual and political fields. Such artists have not only demonstrated their exceptional talents but also their extraordinarily creative capacities to negotiate the difficult contexts conditioned by post-colonial, post-communist, neo-liberalist and globalizing transitions. In their works – not only the production of material objects but also artistic and theoretical discourses – they have managed to provide us with some of the most singular visions in terms of how to live with an unknown and uncertain world at the turn of the millennium. It’s because of the energy and originality of their works that the “international art world,” previously dominated by the West, is now learning to open itself to modes of expression beyond the Eurocentric horizon, and, hence become “global.”

What is especially noteworthy is that this amazing story of “miracle making” has been a story full of adventure and struggles beyond simply aesthetic experiments. By definition it has been political from the outset, since art production in the region has generally been closely related to and resulted from struggles for political, social, cultural and economic freedom, and entangled with the dilemmas between modernity and tradition, totalitarianism and liberalism, collectivism and individualism. It’s in this process of struggle that the most original forms of expression have been created while various modes of production, representation and criticism have also been generated. Along with this excitingly diverse and rich creative landscape, a new self-consciousness of “Asian-ness” has come to the fore of intellectual and social debates that exemplify the re-conceptualization of “global-local” dynamics in the 21st century.

Obviously, the current “takeover” of the market system signifies the potential for better financing and distribution conditions for artistic production in the region, but at the risk of excessive commoditization. What is most challenging now is how to defend and promote the intellectual and social values of art – its critical and cultural positions – amid the turbulence of financial speculation. Dangerously, under the pressure and “seduction” of economic power, contemporary art increasingly has been reduced to commercial product and merged with the entertainment and fashion industries.

Installation view of “On Kawara: Pure Consciousness at 19 Kindergartens” at the Walter and McBean Galleries, San Francisco Art Institute, 2010. Courtesy SFAI.

On the other hand, the question of the public-ness of artistic production, representation and distribution becomes increasingly urgent in the context of an Asian modernization that systematically favors privatization and “market economy.” Urbanization, the most spectacular and dynamic aspect of the modernization process, always leads to gentrification and chaotic expansion at the expense of social conflicts and the disappearance of the public sphere, which has already tended to be weak and fragile across the region. In the field of contemporary art, private collections and institutions are developing rapidly, but public institutions remain poorly funded and politically conservative. In fact, the binary division between the public and the private has not really been a central issue in most Asian countries; it is even more blurred now. How the resources and professional competence generated by the formation of a new market force can help construct reliable public spheres for the art world and public to evaluate and discuss the real values of artistic production is hence a crucial challenge that demands insightful answers. Employing the strategies of grass-roots mobilization and the intensification of proximal productivity, some successful experiments toward that end have already been carried out. But, a much greater number is needed. In other words, the most essential and critical way for the Asian art scene to move beyond the logic of financial speculation is to conceive and construct relevant public infrastructures that can support production of knowledge, ideas and, especially, ideals in terms of creativity and social significance, rather than simply promoting products for consumption.

Certainly, the regional contemporary art scene in Asia is still extremely young and fresh. How to avoid a state of perpetual immaturity induced by market trends when, paradoxically, the market is also the main source of vitality for the regional art scene’s survival and development, is now turned into a common challenge. As in the field of economics, more diverse models of development are badly needed in the unprecedented crisis that we are witnessing – multitudes of modes of production, representation and distribution are necessary.

Qiu Anxiong – Stills from the animation videos (top two) New Classic of Mountains and Seas 1 (2006), 15 min; (middle two) New Classic of Mountains and Seas 2 (2007), 15 min; and (bottom two) Temptation of the Land (2009), 13 min 29 sec. Courtesy Boers-Li Gallery.

At the end, as I mentioned above as a starting point of this discussion, I am organizing a forum with some of the most experienced professionals from Asia and other regions to debate the question: Collecting Asian Contemporary Art: What, When and How?

All the best,

HHR

Archive

Curators on the Move 1-14